Charter Management Organization: STRIVE Preparatory Schools (Denver, CO)

Julie Zhu, Lucas Riccardi, Momo Chapa, Caroline Francisco

Introduction

STRIVE Preparatory Schools is a charter management organization (CMO) comprised of eleven elementary, middle, and high schools in Denver, Colorado. They serve the communities of Far Northeast Denver, Northwest Denver and Southwest Denver, providing free public charter school education to approximately 3500 students in the Denver Public Schools (DPS) district. (“Our Leadership”, 2017) This report provides a comprehensive review of STRIVE’s educational and operational practices, so as to evaluate whether it fulfills its mission of providing quality education to Denver students. Ultimately, it finds that STRIVE shows promise in meeting its purpose, though it has not yet fulfilled it entirely. We argue then, that STRIVE should focus its energy and resources in strengthening its current schools rather than expanding its network further.

Research Method

In order to evaluate data from STRIVE, we conducted a random drawing of six of STRIVE’s eleven schools using an online random number generator. We then compared federal, state and individualized data for these six STRIVE schools with data for DPS, the school district geographically surrounding them.

STRIVE History, Pedagogy and Mission

The first STRIVE Campus was founded ten years ago by Chris Gibbons in Southwest Denver under the belief that “students from all backgrounds deserve a college preparatory education regardless of race, economic circumstance or previous academic achievement.” (“About Us”, 2017) The name STRIVE is an acronym of the school’s core values: Scholarship, Teamwork, Respect, Intelligence, Virtue and Effort.

Since its founding, this charter management organization has expanded to eleven schools, and is planning to expand to seventeen schools by 2022. This expansion has been largely funded through a $6.77 million federal grant STRIVE received in 2015 from the U.S. Department of Education’s Charter School Program (CSP), which is part of a federal effort to grow the number of “high-quality charter schools around the country.” (Neil, 2015)

STRIVE’s pedagogy is focused on college preparation; striving to make college prep the norm and something that can happen close to home. As the word cloud (Figure 4) shows, the word “College” is one of the most frequent words used when selling the school. In addition, it seems that STRIVE is also attempting to incorporate more bilingual education and hire bilingual staff. They recently added a Bilingual Campus Outreach and Engagement Manager and a Middle School Bilingual Science Teacher to their faculty. (“Middle School Bilingual Science Teacher”, 2016; “Bilingual Campus Outreach and Engagement Manager” 2017)

STRIVE’s mission is to ensure all students have an opportunity to access high-quality college-preparatory education, which is a mission they have yet to achieve completely. Although they do serve a disproportionately high number of students of color, they do not necessarily have higher or even on par student achievement in comparison to the the surrounding district schools.

This charter management organization is led by its founder and CEO, Chris Gibbons, a group of school principals, a Board of Trustees, and a Family Council from each school. The Board is comprised of people ranging from the Executive Director of the Carson Foundation, to a partner at a government consulting firm, to an officer at Teach for America, to two involved parent council representatives. (“Our Leadership”, 2017). The Family Council is comprised of the principal, at least one teacher at the school, and at least four parents or guardians of enrolled students, and one community member who does not have a student enrolled or is an employee of the school (“Our Leadership”, 2017). From this structure it seems that STRIVE is attempting to bring community members into decision-making bodies, but more research is needed to know if the voices from the top to the bottom are being heard.

School Demographics

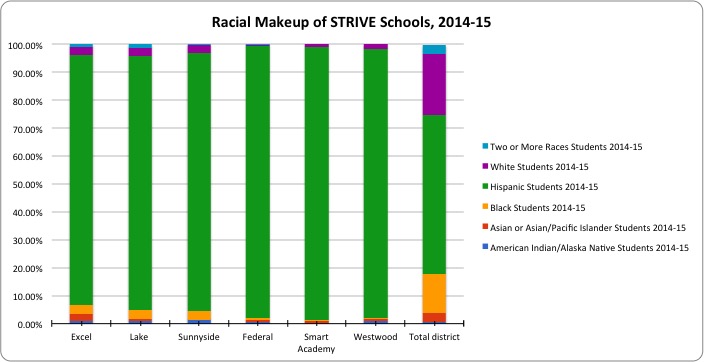

The demographics of STRIVE schools are not representative of those of the entire Denver County School district. The racial makeup of the district is roughly 22% White, 56% Hispanic/Latino, 13% Black and 3% Asian. However, all STRIVE schools enroll student populations that are at least 90% Hispanic/Latino. The largest racial group outside of this racial majority exists at Excel, where 8 Black students are enrolled in a total school population of 238 (3.36%). It is important to note that the district’s racial statistics are not reported on a neighborhood basis. Seeing as STRIVE schools only exist within two areas of Denver – both of which are heavily populated with Hispanic/Latino residents – it is possible that schools in this network have a similar racial makeup to the neighborhood schools within Northwest and Southwest Denver.

Figure 1.

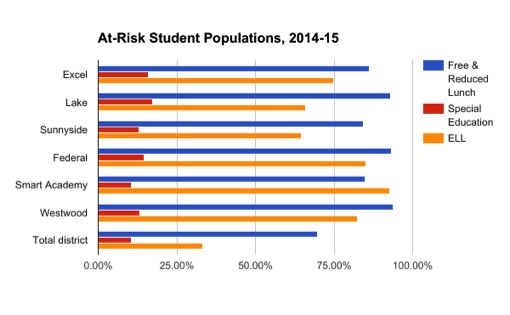

Such distortions exist within the charter network’s other demographics as compared to district data, namely the number of students who received free & reduced lunch and English-language learners. 89% of STRIVE students receive free or reduced lunch, while 70% of students within Denver County Schools receive this service. There is a higher proportion of English-language learners (ELLs) within the STRIVE network — as high as 92% at Smart Academy — than there is at the district level (33%). Each STRIVE school enrolls roughly the same proportion of special education students as the entire district does — within the range of 10.67% to 17.21% (district average 10.65%).

Figure 2.

Student Achievement

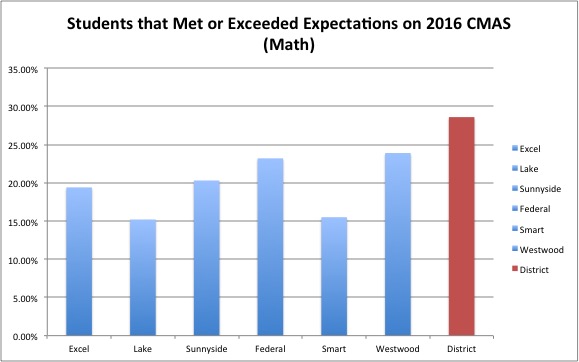

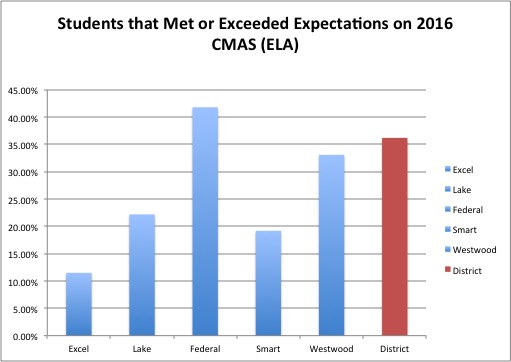

Students in Colorado take PARCC ELA and Math assessments as part of the Colorado Measures for Academic Success (CMAS). Based on this metric of academic achievement, STRIVE schools generally report lower levels of proficiency in English Language Arts and Math when compared to the Denver Public School district as a whole (Fig. 3.) STRIVE schools’ math scores are generally higher than their ELA scores. STRIVE Federal is an exception, showing higher ELA scores than the district in both 2015 and 2016. With some STRIVE schools reporting ELA proficiency as low as 11.5% and math proficiency as low as 15.2%, STRIVE’s mission to academically prepare all students for college is not being achieved. Looking at college acceptance, another measure of student achievement, 90% of STRIVE seniors were accepted to a four-year college in 2015 (Gibbons, 2015, pg. 9). Further studies should explore college-preparedness and college graduation rates of STRIVE students. In sum, STRIVE test scores are below the district average, with some exceptions. While these test scores are only one facet of assessing student learning, they signal that STRIVE needs to improve.

Figures 3a and 3b.

School Discipline

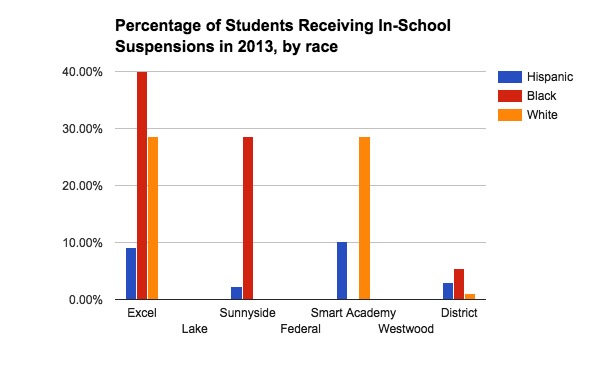

STRIVE schools vary in their school discipline cultures. In-school suspension data shows that some schools in the network (Lake, Federal, and Westwood) have not suspended any students in 2013. Meanwhile, some schools have similar or much higher suspension rates than the district average (2.85%). Excel (11.76%) and Smart Academy (10.25%) suspend students much more frequently than at the district level, while Sunnyside suspends students at roughly the same rate (3.43%). The heavily-skewed racial composition of each school makes it difficult to argue race plays a significant role in discipline. For example, the 40% of Black students who have been suspended at Excel refers to only 4 students, while the 9% of Hispanic/Latino students who have been suspended at Excel refers to 10 students (Fig. 4). School arrest data is consistent among the district, whereby no school arrests have occurred within the STRIVE network or any school in Denver County.

Figure 4.

Marketing & Media

STRIVE makes an evident priority of disseminating polished and accessible marketing materials. The school website features sleek and colorful graphic design with easily navigable tabs, high-quality promotional videos, and all materials available in Spanish (which is important considering the school’s high Latino population). Interestingly, although STRIVE is repeatedly classified as a “no-excuses charter” by outside sources (Quinlan, 2016; Gorski, 2014), the school never identifies itself in this way, nor does it feature images commonly associated with the term. Videos showcase students at work, laughing with one another, and fist-bumping teachers in hallways. And while these interactions seem to be entirely genuine, they are in contrast to other reports of STRIVE’s policies such as “students speak quietly or not at all,” negative marks for a water bottle on a desk instead of the floor, and reprimanding an incorrect action by having the entire class perform the correct action (Quinlan, 2016). Rather than “no excuses,” STRIVE’s marketing seem to focus on ‘high expectations.’

STRIVE’s pitch to parents is a two-part promise: that their children will be safe, and that after STRIVE they can and will attend college. While this approach is not necessarily the most inclusive, it allows parents to select STRIVE with a very specific end-goal in mind. STRIVE’s news presence is mixed. More critical reporting highlights its discipline (Quinlan, 2016), test scores and rapid teacher-turnover rate (Gorski, 2014), and tensions with public schools (see ‘Relationship to District’ section below). Other reporting offers high praise for mentorship programs, successful alumni, and students mobilizing action after the Trump election (“STRIVE Prep in the News”, 2017).

STRIVE has also been open about its dedication to protecting students and teachers regardless of their immigration or legal status. Through Obama’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, Colorado schools can hire Teach for America corps members who have been granted temporary resident status. Although STRIVE and DPS have both received backlash for several undocumented TFA teachers they have hired, they defend their decision by showing how these teachers are positive forces in the school community, especially as role models for students and their families who may also be immigrants or undocumented (Caldwell, 2014).

Figure 5. Word cloud of “The STRIVE Prep Promise” where word size indicates frequency. Notice the prevalence of “college” and “prep.” (“Why STRIVE Prep” 2017) Generated with wordle.net.

Accountability and Oversight

STRIVE’s accessible website makes it easy to view the CMO’s financial history, annual impact reports, and board proceedings. (“Accountability”, 2017) Budgets are available from 2009 to present and describe both the source and allocation of funds, as well as teachers’ salaries and benefits. Apart from controversies surrounding some of its donors, most notably the Walton Family Foundation (see ‘Funding’ section, below), STRIVE itself has never been involved in any scandals, financial or otherwise.

The DPS Board of Education is responsible for the changing tide in policy to embrace charter growth, but has been criticized for its accountability in implementing school choice. In 2011 DPS paid a New York-based consulting firm to design its new school choice system; although Denver parents were initially optimistic about the new system, they ultimately found it to be stressful, confusing, and less rooted in their “choice” than they were made to believe. (Robles, 2011) This finding is consistent with one of the most fundamental critiques of charters, which is that they spend public money on outsourced private services that do not serve the public.

Funding

The STRIVE network is funded by public and private sources, which are published in its annual impact report. Foundations are the main source of private funding, with the Charter School Growth Fund, Daniels Fund, and Walton Family Foundation as the top supporters, giving $500,000 or more to STRIVE in 2015 (Gibbons, 2015, p. 15). The Charter School Growth Fund (CSGF), based in Broomfield Colorado, specializes in scaling up charter schools it deems successful, while the other two foundations are general philanthropic ventures. Notably, CSGF and the Walton Family Foundation see school choice as a priority for improving American public education. The STRIVE network promotes the benefits of school choice, and sees increasing access to quality school options as part of its mission. STRIVE claims, “authentic choice for ALL families is critical to achieving equity.” (Gibbons, 2015, pg. 6). Critics of the Walton Family Foundation point to the privatizing effects of the school choice movement that amplify the voices of billionaires in matters of public education. The Waltons had a hand in funding 20% of the charter schools that opened in 2015, which makes it hard to deny that they have an immense influence on the charter sector as a whole- its goals, measures of success, and importantly, how big it is (Strauss, 2016). As a growing charter network receiving funds from GCSF and the Walton Foundation, STRIVE seems aligned to some degree with the school choice movement.

Staffing

STRIVE aims to “attract, recruit and retain exceptional talent” and to “engage in a culturally-responsive community” (“Join Our Team” 2017). These goals are reflected in the staff: 80% of STRIVE staff are returning staff, 50% are Spanish speakers, and 20% are first generation college students. The stat that 80% of staff are returning implies lower teacher turnover than probably exists because staff includes central office employees. Furthermore, when STRIVE saw a dip in test scores in 2014, teacher turnover was cited as one of the explanations (Gorski 2014). Teach for America certainly has a relationship with STRIVE, as Crystal Rountree, a Teach for America executive, sits on STRIVE’s board (“Our Leadership” 2017). STRIVE not only recruits teachers and administrators, but also trains them. The STRIVE network has a teacher residency program that trains teachers in STRIVE schools. Additionally, teachers at STRIVE can participate in the Principal Fellows program to train to become school administrators. The network emphasizes professional development and growth for teachers (“Join Our Team” 2017).

Relationship to the District

STRIVE has a complicated relationship with the surrounding district, DPS. The DPS Board of Education, headed by Superintendent Tom Boasberg, has been responsible for the shift to embrace school choice and charter growth in Denver, and the board’s support for Boasberg’s proposed reforms has increased from 3-4 to 6-1. (Torres, 2013) Yet those loyal to public schools within the district have expressed feelings of disenfranchisement, both financial and political. Charter growth in Denver meant increased options for families, but it also meant a new charter could become a zoned neighborhood’s ‘default’ and admission into a traditional public school was no longer guaranteed. (Friedman, 2015)

As STRIVE expanded, DPS implemented a series of forced co-locations that housed the growing charter in the same buildings as existing public schools rather than building new sites. Olivia Friedman, a high-schooler at public North High School which was forced to cohabitate with STRIVE, wrote in a Denver Post op-ed: “It would mean we would be required to share the cafeteria, the library, and other facilities. Many believed it would disrupt North’s positive growth that had been occurring in recent years. Above all, it would be sending a clear message to the North students and community: We aren’t good enough. A traditional high school education isn’t good enough.” (Friedman, 2015)

Conclusion

Throughout the last decade, STRIVE has expanded drastically from one to eleven schools in the charter management organization. However, could this be a case of “replicating failure” expansion? (Zernike, 2016) Based on the controversy with school discipline, the high turnover rates of teachers in years of expansion, the low levels of student achievement, tensions with neighboring public schools, and other issues, we argue that this CMO is doing just that. STRIVE has shown promise in serving its community by offering bilingual education and helping students get to college, but the network’s weaknesses demand attention. Therefore, before STRIVE continues expanding to other schools, we suggest they should invest heavily in combatting the issues mentioned in this report to make sure they are replicating success and quality education.

Works Cited

Buckley, P., Ph.D., & Muraskin, L., Ph.D. (2009). Graduates of DPS: College Access and Success (pp. 1-45, Rep.). The Piton Foundation, The Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education.

Caldwell, A. (2014, April 14). Caldwell: A teacher fluent in English, Spanish and hope. The Denver Post. Retrieved March 30, 2017, from http://www.denverpost.com/2014/04/14/caldwell-a-teacher-fluent-in-english-spanish-and-hope/

Friedman, O. (2015, August 14). Colorado Voices: DPS: Here is what we want in our schools. The Denver Post. Retrieved March 30, 2017, from http://www.denverpost.com/2015/08/14/colorado-voices-dps-here-is-what-we-want-in-our-schools/

Gibbons, C. (2015). 2015 Impact Report: Lessons Earned: Celebrating A Decade of Discovery (pp. 1-16, Rep.). Denver, CO: STRIVE Preparatory Schools.

Gorski, E. (2014, August 15). Latest scores are big test for growing Denver charter school network. The Denver Post. Retrieved March 30, 2017, from http://www.denverpost.com/2014/08/15/latest-scores-are-big-test-for-growing-denver-charter-school-network/

Neil, L. (2015, September 29). STRIVE Prep Awarded $6.77 Million Federal Grant. Retrieved March 29, 2017, from http://www.striveprep.org/strive-preparatory-schools-named-sole-colorado-charter-school-network-to-receive-u-s-department-of-educations-charter-schools-program-grants/

Quinlan, C. (2016, December 13). Charter school network rejects any hint of ‘defiance’ from students. Retrieved March 30, 2017, from https://thinkprogress.org/inside-a-charter-school-that-enforces-a-culture-of-compliance-f8b7ff4356ec

Robles, Y. (2011, December 31). DPS’ new school choice system stressing out some parents. The Denver Post. Retrieved March 30, 2017, from http://www.denverpost.com/2011/12/31/denver-public-schools-new-school-choice-system-stressing-out-some-parents/

Strauss, V. (2016, January 27). Walton family steps up support for school choice with $1 billion pledge. Retrieved March 29, 2017, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2016/01/27/walton-family-steps-up-support-for-school-choice-with-1-billion-pledge/?utm_term=.9548c953cb89

STRIVE Preparatory Schools. (2017). About Us. Retrieved March 29, 2017, from http://www.striveprep.org/about-us/

STRIVE Preparatory Schools. (2017). Accountability. Retrieved March 30, 2017, from http://www.striveprep.org/about-us/accountability/

STRIVE Preparatory Schools. (2017, February 28). Bilingual Campus Outreach and Engagement Manager. Retrieved April 04, 2017, from https://striveprep.catsone.com/careers/index.php?m=portal&a=details&jobOrderID=8971514

STRIVE Preparatory Schools. (2017). Join Our Team. Retrieved March 29, 2017, from http://www.striveprep.org/join-our-team/

STRIVE Preparatory Schools. (2016, November 04). Middle School Bilingual Science Teacher. Retrieved April 04, 2017, from http://striveprep.catsone.com/careers/index.php?m=portal&a=details&jobOrderID=8361047

STRIVE Preparatory Schools. (2017). Our Leadership. Retrieved March 29, 2017, from http://www.striveprep.org/about-us/our-leadership/

STRIVE Preparatory Schools. (2017). STRIVE Prep in the News. Retrieved March 30, 2017, from http://www.striveprep.org/about-us/strive-in-the-news/

STRIVE Preparatory Schools. (2017). Why STRIVE Prep. Retrieved March 30, 2017, from http://www.striveprep.org/enroll-a-student/940-2/

Torres, Z. (2013, November 5). DPS candidates backing reform poised for wins. The Denver Post. Retrieved March 30, 2017, from http://www.denverpost.com/2013/11/05/denver-public-schools-candidates-backing-reform-poised-for-wins/

Zernike, K. (2016, June 28). A Sea of Charter Schools in Detroit Leaves Students Adrift. NYTimes. Retrieved April 1, 2017, from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/29/us/for-detroits-children-more-school-choice-but-not-better-schools.html?_r=1