Legislating School Climate

Examining Los Angeles Unified School District’s Ban of Suspension for “Willful Defiance”

Introduction

In January 2014, the U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division and the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights issued a joint federal guidance stating that school discipline was discriminatory based on race and ethnicity and that exclusionary discipline “creates the potential for significant, negative educational and long-term outcomes, and can contribute to what has been termed the ‘school to prison pipeline’” (Joint “Dear Colleague Letter”, 2014). The guidance reminded schools of their obligation to serve students in a non-discriminatory manner and offered recommendations for making discipline more equitable (Joint “Dear Colleague Letter”, 2014). This guidance was recognition on a national level that unjust school discipline practices are a civil rights issue for students of color. More locally, parents and students have understood this reality for years, and worked to change it. Educators across the country understand that traditional exclusionary discipline practices just aren’t effective. Alternatives to suspension, such as restorative justice, are being implemented in schools and districts that recognize that students who misbehave often need more support rather than less time in class.

Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) has been working to reform their discipline culture for over a decade, moving away from “zero tolerance” and actually implementing a district-wide policy that limits schools’ ability to suspend students and requires implementation of alternative discipline practices. What does it look like when a district recognizes the injustice and ineffectiveness of suspensions, and tries to ban them? Can districts or states use legislation to reform negative discipline culture? Overall, the “School Climate Bill of Rights” adopted by the Los Angeles Unified School Board has successfully decreased suspensions in the district, and driven change in the state of California. LAUSD can be seen as a model of what districts can do to reform discipline. However, while district policy is critical, discipline reform is most important at the school level, as discipline culture is the product of daily interactions between students, teachers, and administrators.

Policy Background: Local Initiatives and State Laws

In May 2013, the board of the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) voted to end schools’ ability to suspend students for “willful defiance.” Willful defiance is described in the California Education Code as: “Disrupted school activities or otherwise willfully defied the valid authority of supervisors, teachers, administrators, school officials, or other school personnel engaged in the performance of their duties” (Cal. Education Code, 2009). Parents pushed for the ban, as “willful defiance” suspensions are disproportionately applied to at-risk students, such as students of color, english language learners, and students with disabilities (ACLU, 2015). As part of the long list of violations that could lead to a student’s suspension in LAUSD schools before 2013, “willful defiance” was targeted as the most vague and subjective reason for taking a student out of class. Statewide, “Willful defiance accounts for 43% of suspensions issued to California students, and is the suspension offense category with the most significant racial disparities” (ACLU, 2015). Current proponents of best practices in discipline say that out-of-school suspension should only be a last resort, rather than an answer to some of the minor behaviors that can full under “willful defiance” (Losen and Martinez, 2013, p. 2).

The suspension ban in L.A. was passed as part of a larger “School Climate Bill of Rights” that mandated implementation of restorative justice programs, disaggregated data collection tracking school discipline, and a system to file formal complaints regarding discipline (School Climate Bill of Rights, 2013). When the bill passed, NPR reported that “Hundreds of students gathered downtown to testify about the problem of zero tolerance and to celebrate the end of willful defiance.” (Rott, 2013). Parents’ opposition to suspensions was voiced by CADRE, a parent organizing group that had been tracking suspension data and arguing that suspensions can lead students to drop out of high school (Rott, 2013).

The next year, the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights issued the federal guidance regarding discipline and the State of California followed with legislation passed in September 2014 that banned suspension for “willful defiance” in grades K-3, and expulsion for “willful defiance” in all grades (ACLU, 2015). California was the first state to pass such a law and the signing of AB 420 was an important step towards re-thinking discipline in this country’s public schools (ACLU, 2015). Los Angeles Public Schools are are at the forefront of the California’s move away from exclusionary discipline, as the board had adopted a plan that was more comprehensive than the state before the state law was even passed.

Research on Suspensions

Why is reducing suspensions such an important goal? Suspensions are exclusionary and punitive practices that can harm students. Research supports the idea that suspensions do more harm than good for students. At the secondary level, students who have been suspended are more likely to have lower standardized testing outcomes and a higher risk of dropping out of high school (Wood, 2016, p. 11). In fact, “being suspended even once in ninth grade is associated with a twofold increase in the likelihood of dropping out” (Losen and Martinez, 2013, p. 1). Heavy use of exclusionary discipline has negative consequences for individual students as well as schools. Schools with “high rates of exclusionary discipline” are shown to have lower scores on state achievement tests, even when controlling for factors such as poverty, race, school size, and school location (Wood, 2016, p. 11).

Research shows that suspensions are bad for all students, but also that suspensions are disproportionately applied to students based on race, gender, and ability. Nationally in the 2011-2012 school year, “32–42% of Black/African American students were suspended or expelled,” while “Black/African American students represented 16% of the student population” (Wood, 2016, p. 2). On the whole, male students are suspended more frequently than female students (Wood, 2016, p. 9). However, black female students are suspended are higher rates than white or hispanic female students (Wood, 2016, p. 5). Looking at the exact same behavior, a study in 2011 found that “African American and Latino students were more likely than their White peers to receive expulsions or OSS as consequences for the same or similar problem behaviors. (Wood, 2016, p. 5) This type of bias for similar behaviors is why banning suspension for vague categories such as “willful defiance” is so important. According to the U.S. Department of Education Office of Civil Rights, “students diagnosed with an educational disability were more than twice as likely to receive an OSS (13%) than their non-disabled peers (6%)” (Joint “Dear Colleague” Letter, 2014). In their study for the UCLA Civil Rights project, Losen and Martinez point out that intersections of these categories can demonstrate immense inequalities: “36% of all Black middle school males with disabilities were suspended one or more times” in the 2009-10 school year (2013, p. 3). School discipline as it currently operates is discriminatory, as students of color and students with disability are especially vulnerable to suspension.

This discrimination in discipline contributes to the “school-to-prison pipeline” in the United States (Graham, 2016). “Zero-tolerance” discipline policies of the late 80s and early 90s and the high-stakes accountability of NCLB in the 2000s have provided schools with the tools, and actually incentivized them, to exclude students (Graham, 2016). Consequently, “Standardized testing and increased suspensions have the effect of pushing students, especially students of color and students with disabilities, out of schools and into the juvenile and criminal justice systems” (Graham, 2016, p. 2) Once students internalize negative perceptions of themselves as “troublemakers” or come in contact with the criminal justice system, the effects can be devastating (Graham, 2016).

Suspensions are not only harmful to students in the long run, but they are missed opportunities for positive intervention. Pedro Noguera argues that exclusionary discipline practices “effectively deny targeted students access to instruction and the opportunity to learn and do little to enable students to learn from their mistakes and develop a sense of responsibility for their behavior” (2008, p. 133). Disruptive behavior that could fall under the umbrella of “willful defiance” should be interpreted as a signal that a student needs more support. Noguera continues, “When we locate discipline problems exclusively in the students and ignore the school and local contexts in which problematic behavior occurs, we ignore the most important factors that give rise to problematic behavior” (2008, p. 136). The idea of locating discipline problems in areas beyond the individual student, such as trouble at home, conflicts with peers, or disengagement from academics, is critical to improving school culture.

Many opponents of exclusionary discipline are doing more than exposing a problem, they are offering solutions that will make discipline culture more positive and fair. Restorative Justice is one alternative to exclusionary discipline that involves holding an offender accountable for their actions, “often by requiring the offender to face the victim and engage in restoration of what was lost” (Owen, et. al, 2015, p. 10). Typically, restorative justice is carried out by trained outside groups or peer juries that facilitate restorative circles to repair relationships between students (Owen, et. al, 2015, p. 10). Another strategy is professional development and support for teachers, which also requires time and resources (Owen, et. al, 2015, p. 9). A variety of programs are in place around the country, but the underlying principles should emphasize re-engagement with the classroom, rather than exclusion. Noguera writes, “By relying on alternative discipline strategies rooted in ethics and a determination to reconnect students to learning, schools can reduce the likelihood that the neediest and most disengaged students, who are frequently children of color, will be targeted for repeated punishment” (2008, p. 136). Alternatives to suspension can decrease race-based discrimination in discipline that disproportionately harms students of color.

Effects of Discipline Reform in Los Angeles

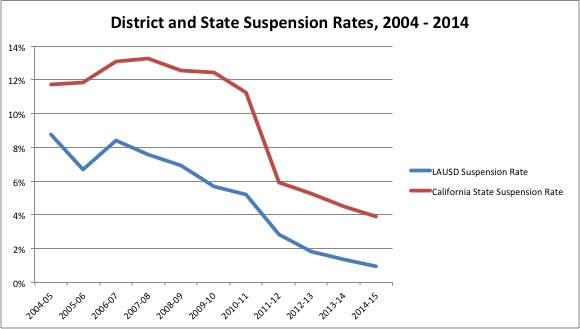

Though the School Climate Bill of Rights was passed in 2013, discipline policy reform has been in the works in Los Angeles for over a decade. For instance, the LAUSD “passed the Discipline Foundation Policy in 2005, thereby becoming a national leader through the District-wide adoption of the proven, evidenced based whole-school alternative discipline strategy, positive behavior intervention and supports” (Special Board Meeting, 2012). These sustained efforts have contributed to significant change at the district level: suspension rates in the district have decreased from 9% in 2004-05 to 1% in 2014-15 (students not duplicated) (DataQuest, 2013). The racial gap in discipline rates has also decreased, though Black students and American Indian students are still suspended at disproportionately high rates compared to other racial/ethnic groups (Losen and Martinez, 2013, p. 14). Importantly, state and national policies have followed the district’s lead, rather than the other way around. LAUSD’s action on discipline, guided by parents, teachers, administrators, and students, has been effective at reducing suspensions.

The state of California as a whole has also demonstrated steady declines in suspension rates. From 2012 to 2104, statewide suspension rates dropped by over three percentage points. In fact, “77% of this reduction in total suspensions is attributable to fewer suspensions in the category of disruption or willful defiance,” demonstrating the impact of legislation like AB 420 and district policies that ban suspension for willful defiance (Losen, et al., 2015, p. 4). Losen, et al. comment, “The local efforts of members of many school communities in districts across the state not only inspired the state to act but also contributed to the patterns” of statewide decrease in suspension rates (2015, p. ii). District-level action, in places such as Los Angeles, San Diego, Berkeley, and Alameda, has been instrumental in decreasing state-level suspension rates (Losen, et. al, 2015).

Figure 1. State and district rates have decreased over time. Los Angeles Public Schools have been working since 2005 to reform discipline, showing that this issue requires sustained effort.

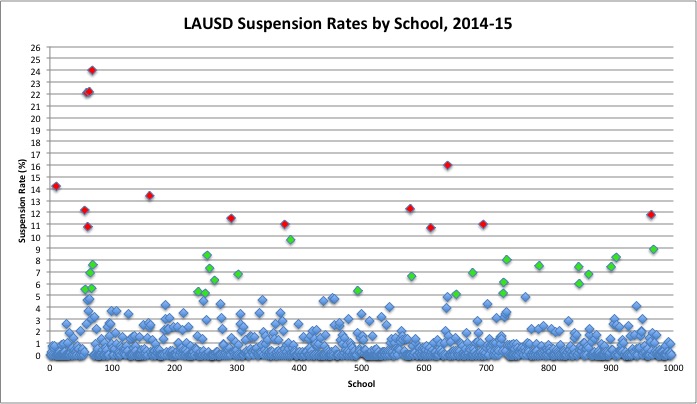

Across all of LAUSD’s almost 1,000 schools, the average suspension rate in 2014-15 was 0.9%. Most of the district’s schools are clustered around this average, which is quite low compared to the national suspension rate of 10.1% for secondary schools (data from 2011-12) (Nationwide Suspension Rates). However, there are significant outliers within the district. Fourteen schools in the district have suspension rates higher than 10%, meaning one in ten children at those schools was suspended at least once in the 2014-15 school year (Figure 2). Of those fourteen schools, twelve are charters, one is a magnet, and one is a regular public school. Based off this short list of the schools with the highest suspension rates, charter schools are not making the same improvements in decreasing suspensions that district schools have shown. Charter schools have received backlash in cities across the country for their tendency to employ strict discipline techniques, resulting in higher suspension rates. The California NAACP recently proposed a moratorium on expansion of the charter sector, citing discipline as a major concern (Nix, 2016).

Figure 2. Each point represents a school in LAUSD. Points in red show schools with suspension rates above 10%. Points in green show schools with suspension rates below 10% and above 5%. Points in blue show schools with suspension rates below 5%.

When it comes to discipline, district-level action has been critical, but perhaps the most important level for students is school-level change. Suspension rates are not just numbers, but signals of school climate that affect every student in the classroom, not just the students who face suspension. Garfield High School in L.A. is an example of one school’s efforts to shift discipline culture. When Jose Huerta became principal in 2010, his mission was to “enhance and improve the instruction” at Garfield High School (NPR Staff, 2013). Reducing suspensions, which he and his team of teachers have done significantly, was only one component, or perhaps a result, of that mission. Huerta sees suspensions as reactionary and assumes that problems outside of class are causing disruptive behavior (NPR Staff, 2013). When a student exhibits problematic behavior, Huerta says that “teachers act quickly with counselors or the student support team to ‘find out what the real deal is” (NPR Staff, 2013). With limited funds to spend on additionally school counselors or supports, Huerta reached out to community groups (NPR Staff, 2013). He claims that “connecting with kids and having a strong instructional program” are the keys to lower rates of exclusionary discipline (NPR Staff, 2013).

Garfield High School did not suspend any of its 2,500+ students in the 2014-15 school year (DataQuest, 2013). To decrease, and eventually eliminate, suspensions at Garfield, it took determined administrators and teachers with a comprehensive view of positive school culture that emphasized student engagement, community involvement, and the social-emotional needs of students. However, not every teacher and administrator shares Huerta’s views. Furthermore, there are barriers in place currently that make improving discipline culture more difficult than it needs to be.

Challenges to Implementing a Suspension Ban

Not all educators are supportive of the suspension ban. A common criticism from opponents of the ban is that well-behaved students will suffer if disruptive students are not removed from the school. One Los Angeles teacher said “If I see the classroom environment is suffering, that the students are getting scared, I will remove the problem student because my other students have rights, too” (NPR Staff, 2013). However, quantitative studies have tentatively shown that “in California, lower district suspension rates are correlated with higher district achievement” (Losen, et. al, 2015, p. ii). Additionally, a 2014 study of Kentucky secondary schools found that “higher levels of exclusionary discipline within schools over time generate collateral damage, negatively affecting the academic achievement of non-suspended students in punitive contexts” (Perry and Morris, 2014, 1). These findings suggest that excessive use of exclusionary discipline affects the entire climate of the school, making it an environment less conducive to learning for all students.

Discipline reform is not impeding academic achievement, as some opponents have suggested, but the real experiences and concerns of educators should not be ignored. Taking away schools’ abilities to suspend without offering resources or training for suspension alternatives is a halfhearted solution to the problem of exclusionary discipline. Isabel J. Morales, a high school social studies teacher in L.A., supported the school board’s initiative but expressed that some of her colleagues felt “powerless” LA teachers says some feel powerless (Anderson, 2015). Morales points out a disconnect between district policy and teachers’ attitudes or resources, saying, teachers “still have their same biases, and now they’re extra angry because their one method was to kick [insubordinate students] out, and there’s just extra hostility” (Anderson, 2015).

In schools where the policy may have felt like an unwelcome imposition from the school board, there have been unintended consequences. Assistant Principal at L.A.’s Markham Middle School admitted, “students were at times sent home without being officially suspended because the behavior does not meet legal grounds for suspension” (Watanabe, 2014). Several African-American parents at Markham have claimed that the predominantly Latino administration has treated their students unfairly. Parent Talia Slone said “When it’s Hispanic kids, [administrators] take the time and call parents but do not take the time with African Americans” (Watanabe, 2014). Organizers from CADRE, the same parent group that rallied for the suspension ban, have alleged that schools are now working around formal suspensions to send students home (Watanabe, 2014).

Another school under scrutiny for such practices, Gompers middle school, has recognized the problem and taken steps to improve. Gompers Principal Traci Gholar used to use suspensions as a way “to drive home to families that she was intent on building a safe, orderly and positive school climate” (Watanabe, 2014). Gholar’s sentiment represents a challenge to discipline reform- that different administrators have different ideas on how to create a positive school climate. Charged by higher ups with the task of reducing suspensions, Gholar requested resources and was able to get her school “a conflict resolution specialist, a restorative justice coordinator, more campus aides, performing arts events and other activities” (Watanabe, 2014). The first years of the suspension ban’s implementation show that schools need resources and support, whether that comes from the district or community organizations.

Conclusion

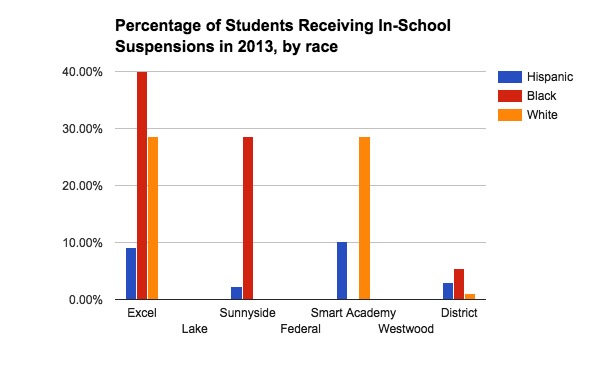

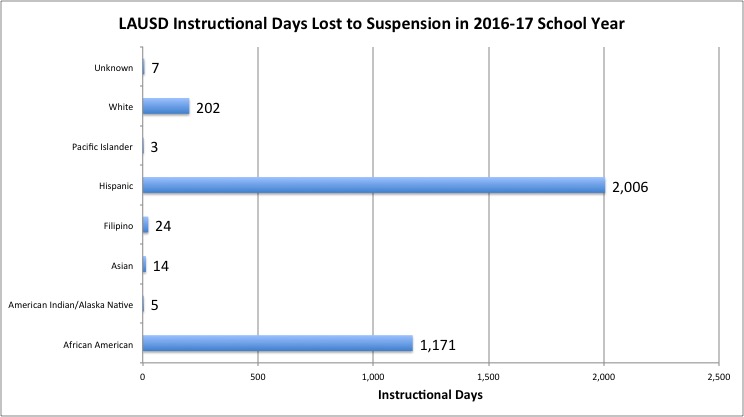

In many respects, Los Angeles Unified Public Schools have provided a model for reducing suspensions in large urban districts. The district’s “School Climate Bill of Rights” was the product of years of discipline reform and advocacy from parents, teachers, and students. The state of California followed suit with legislation that has begun to have statewide effects, showing that districts, especially a large urban district like LAUSD, have power to drive large-scale change. While state legislation is promising, discipline is an issue that is extremely close to students and teachers. Even in Los Angeles, an exemplar of a large urban district with low suspension rates, schools are still struggling to implement a more positive discipline culture. Anecdotal evidence suggests that for schools to embrace the suspension ban, they need administrators and teachers that believe in it and/or additional resources to implement restorative justice practices, train teachers, and provide additional support to students. LAUSD should focus on supporting schools that are struggling to implement the ban as well as strengthen mechanisms for families to report instances where students are sent home, but not technically suspended. Racial disparities in discipline remain (Figure 3). In the current school year, as of mid-April, African-American students in L.A. public schools had lost 1,171 days of instruction due to suspension. While African-American students make up 8.3 % of the district’s total enrollment, they accounted for 34% of lost instructional days (Student Discipline Reports, 2017). In sum, banning suspension for “willful defiance” is effective and worthwhile. However, much of that effectiveness comes from the local support of educators and communities, rather than the power of the legislation itself. Furthermore, even in districts with the lowest suspension rates, racial disparities in discipline and schools with high rates of exclusionary discipline are still present.

Figure 3. Hispanic students have lost the most instructional days due to suspension this school year, followed by African-American students.

Works Cited

ACLU. California Enacts First-in-the-Nation Law to Eliminate Student Suspensions for Minor Misbehavior. (2015, September 27). Retrieved from https://www.aclunc.org/news/california-enacts-first-nation-law-eliminate-student-suspensions-minor-misbehavior

Anderson, Melinda D. (2015, September 14). Will School-Discipline Reform Actually Change Anything? The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2015/09/will-school-discipline-reform-actually-change-anything/405157/

DataQuest. (2013, November 8). California Department of Education. Retrieved from http://dq.cde.ca.gov/dataquest/.

Graham, J. (2016). Race, Resegregation and the School to Prison Pipeline in Mecklenburg County (Order No. 10239026). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (1864760225). Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/1864760225?accountid=15172

Joint “Dear Colleague” Letter. (2014, January 8). U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/letters/colleague-201401-title-vi.html

Losen, D.J., Keith, M.A. II, Hodson, C,L., Martinez, T.E., & Belway, S. (2015). Closing the School Discipline Gap in California: Signs of Progress. K-12 Racial Disparities in School Discipline. UCLA: The Civil Rights Project / Proyecto Derechos Civiles. Retrieved from: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/65w0k9tm

Losen, Daniel J; & Martinez, Tia E. (2013). Out of School and Off Track: The Overuse of Suspensions in American Middle and High Schools. K-12 Racial Disparities in School Discipline. UCLA: The Civil Rights Project / Proyecto Derechos Civiles. Retrieved from: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/8pd0s08z

Nationwide Suspension Rates at U.S. Schools (2011-12). The Center for Civil Rights Remedies at the Civil Rights Project/Proyecto Derechos Civiles. Retrieved from http://www.schooldisciplinedata.org/ccrr/index.php

Nix, Naomi. (2016, August 4). California NAACP proposes moratorium on new public charter schools, sparking backlash from other civil rights advocates. LA School Report. Retrieved from http://laschoolreport.com/naacp-may-double-down-on-charter-school-opposition-as-civil-rights-allies-strongly-disagree/

Noguera, Pedro. (2008) What Discipline is For: Connecting Students to the Benefits of Learning. In Pollack, M. (ed.), Every Day Anti-Racism: Getting real about race in school. New York, NY: The New Press.

NPR Staff. (2013, June 2). Why Some Schools Want to Expel Suspensions. NPR. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/2013/06/02/188125079/why-some-schools-want-to-expel-suspensions.

Owen, J., Wettach, J., Hoffman, K.C. (2015). Instead of Suspension: Alternative Strategies for Effective School Discipline. Duke Center for Child and Family Policy and Duke Children’s Law Clinic. Retrieved from https://law.duke.edu/childedlaw/schooldiscipline/downloads/instead_of_suspension.pdf

Perry, Brea L. & Morris, Edward W. (2014, November 5). Suspending Progress: Collateral Consequences of Exclusionary Punishment in Public Schools. American Sociological Review Vol 79, Issue 6, pp. 1067 – 1087. Retrieved from 10.1177/0003122414556308.

Rott, Nathan. (2013, May 15). LA Schools Throw Out Suspensions For ‘Willful Defiance.’ NPR. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/2013/05/15/184195877/l-a-schools-throw-out-suspensions-for-willful-defiance

School Climate Bill of Rights. (2013, May 14). Los Angeles Unified School District. Retrieved from http://notebook.lausd.net/pls/ptl/docs/PAGE/CA_LAUSD/FLDR_ORGANIZATIONS/FLDR_OFFICE_OF_SUPE/ATTACHMENT%20C-2_0.PDF

Special Board Meeting Order of Business (2012, June 28). Board of Education of the City of Los Angeles. Retrieved from https://boe.lausd.net/sites/default/files/06-28-12OrderofBusiness_0.pdf.

Student Discipline Data Reports- Suspension: 2016-2017 School Year. (2017, April 11). Los Angeles Unified School District. http://schoolinfosheet.lausd.net/budgetreports/getdrpdf?reporttype=LAUSDSummary&schoolyear=20162017&district=&school_name=&school_code=&prop=TCIBCfwDEq8ZVcVy%2B845cmjEOCtnQngVISEUc%2B5MvswgVMpNQihYChXSu8LHkJ7r1zjjIZslYyAm%0D%0AIlROOwZFKwcM5dEt4BbNebFz6qJtR7PGruvrrs6NCrZygMDcuzirYLDkqqnAbHX9IUUkRZvJlCE%2F%0D%0AOOAhqmqUM9QEiUoQZ%2FBNUYuE4TUCjHnVANkYRkQ%2F

Suspension or Expulsion, Cal. Education Code § 48900. (2009). Retrieved From https://www.gusd.net/cms/lib/CA01000648/Centricity/Domain/58/EC_%C2%A748900.pdf.

Watanabe, Teresa. (2014, May 31). L.A. Unified suspension rates fall but some question figures’ accuracy. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from http://www.latimes.com/local/la-me-lausd-suspend-20140601-story.html

Watanabe, Teresa. (2014, May 21). Watts school officials are targeting black students, some parents say. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-watts-students-suspend-20140521-story.html.

Wood, J. (2016). Predicting School Success From A Disruption in Educational Experience. (Electronic Thesis or Dissertation). Retrieved from https://etd.ohiolink.edu/