Sex Ed in the Era of Trump: City-Led Reform and Standardization on a Scale that Works

Caroline Francisco / Public Schools & Public Policy / May 2017

Executive Summary

This paper is not intended solely to make the case for comprehensive sexual health education in the United States, nor is it intended as a complete and holistic curriculum proposal; a vast body of research and literature have already established both. Instead, what I hope to explore here is, who should lead the way? Why have some attempts to standardize sex ed been non-effective, and where are more effective policies in place? What political actions can be taken to bring better sex education to American students, and from where should those actions stem? Ultimately, my research suggests two findings. First: that American cities, as mid-levels between school-by-school/teacher-by-teacher action and federal government action, have the most potential to enact effective standardized sex education curricula in schools. I highlight the 2013 implemented in Chicago Public Schools and analyze its effects. Second: that despite a public school system labeled “antiquated,” “failing,” and under fire from the federal government, sex education is a particular area where public schools have potential to excel. (American Federation for Children 2015) (PhilanthropyRoundtable 2013)

Introduction: What is at Stake

Arguing for radical reform of sex education often requires fighting for its existence in the first place. Due to the topic’s charged moralized nature, sex ed has a long history of criticism, especially from religious advocates and those who believe sexual and reproductive conversations belong exclusively in the privacy of the home. Yet in practice, only 43% of parents say they feel “very comfortable” talking to their children about sex, and 50% of teens say they feel uncomfortable talking about sex with their parents. (Planned Parenthood 2011) (Planned Parenthood 2012) Following an incident in Chicago Public Schools (discussed later in this paper’s “Evidence” section), parent Rachel Gigliotti described topics of “sex with a condom, sex without a condom, sex with lube” as “things I wouldn’t even discuss in my own personal life.” (NBC Chicago 2014) If parents are unwilling to discuss fundamental topics like contraception and lubrication in their personal lives, much less with their children, the question is begged: then where, if at all, will young adults learn?

This paper treats education as a public good, and comprehensive sexual education (CSE) as a vital component of that public good. Even differing philosophies of the ‘purpose of education’ offer ample justification for curriculum that includes not only ‘core’ subjects like math and history, but also topics of personal biology, health, safety, risk, and social skills. David Labaree (1997) groups “the root of educational conflicts” into three alternative goals for American education…: democratic equality (schools should focus on preparing citizens), social efficiency (they should focus on training workers), and social mobility (they should prepare individuals to compete for social positions.)” Even though the last goal treats education as a private good, CSE arguably serves all three goals, as its overarching aim is not to encourage premature sexual activities but to empower young people to know the facts, know their rights, and make informed decisions.

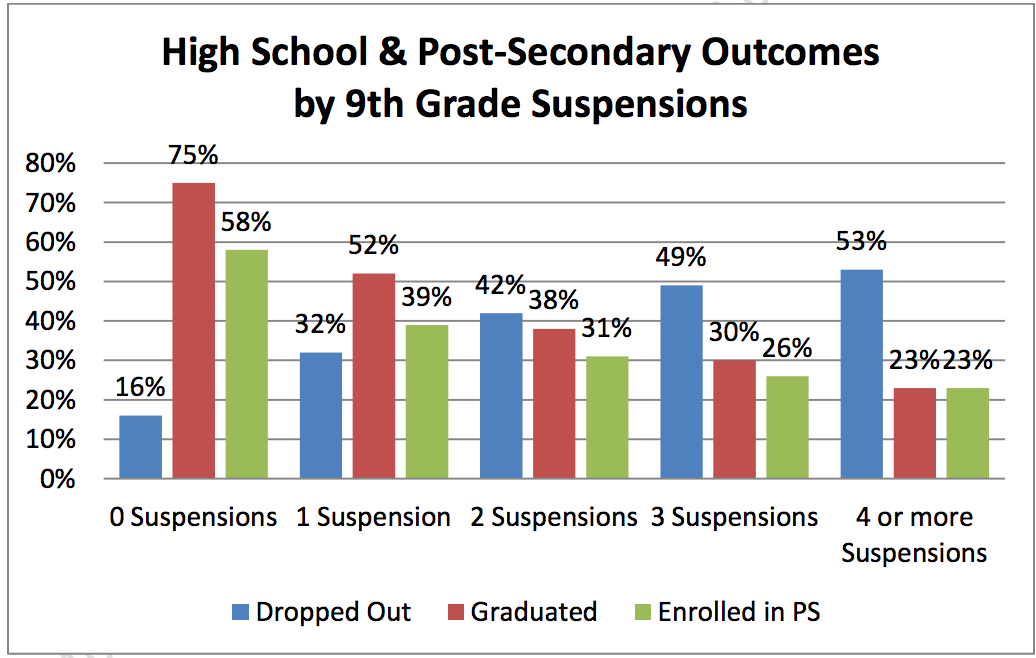

Consider the topic of informed consent—when a young person is taught that they equally have the right to say “yes” and the right to say “no,” and a universal right to have their answer honored, they are not only more equipped in sexual situations, but in everyday interactions, in the workplace, legally, and in any situation involving power dynamics. The ripple-effect social implications of this are huge; consider that in 2016, 46% of Americans voted for a candidate well-known for saying, about “beautiful women,” “Grab ’em by the pussy. You can do anything.” (Leip 2016) (NY Times 2016) Would this be the case if every American were educated about consent from a young age? Furthermore, plenty of evidence suggests that good sex education keeps more kids in school longer, to complete the rest of their education: “Nearly one-third of teen girls who have dropped out of high school cite early pregnancy or parenthood as a key reason. Only 40 percent of teen moms finish high school, and less than two percent of teen mothers (those who have a baby before age 18) finish college by age 30.” (Shuger 2012)

The term “comprehensive” sex ed has emerged to distinguish itself from “abstinence-only” sex ed which advises—in many cases morally requires—abstaining from sexual activity until marriage. (By extension, this implies that humans relinquish their right to sexuality if they do not conform to social constructs of marriage.) Abstinence-only education is historically ridden with value judgments against sexually active individuals and double standards against women. In various abstinence-only curricula around the country, a woman who has lost her virginity before marriage is likened to a dirty sneaker, a chewed stick of gum, a used piece of tape, or a piece of chocolate that has been passed around the class: used, dirty, undesirable, and worthless. (LastWeekTonight 2015) (Semuels 2014) This sends messages to young girls that they exist to marry and be valuable to men, that sexual activity devalues them, that “they cannot be sexual beings in the way that boys can,” and for female victims of sexual assault, that the fault is theirs. (Beyoncé 2014)

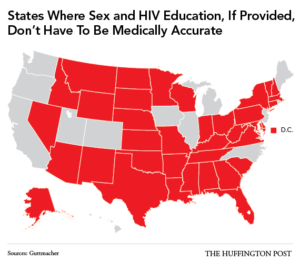

Is this kind of education the norm or the outlier? What does sex ed look like in most American public schools? A proper diagnosis is elusive; despite the growing trend towards accountability measures in core subjects, almost no accountability or effective standardization exists for sex ed. Research shows however that even in 2017, sex ed in America looks more like the “chewed stick of gum” model than not. Guttmacher Institute, which provides the leading data on sex ed standards, reports that as of May 1, 2017, only 24 states and Washington DC mandate sex education, and only 13 require that the information presented be “medically accurate.” 37 states require that when sex ed is offered, abstinence be either “stressed” (26) or “covered” (11), while only 18 states require offering information on contraceptives. Only 2 states explicitly prohibit sex ed programs from promoting religion, and in 3 states—Alabama, South Carolina, and Texas—any information presented on non-hetero sexual orientation must be explicitly negative. Furthermore, countless schools rely on outsourced curriculum materials—public or private—to show in their classrooms, which means that variance from school to school is almost impossible to track. Some kids are getting Planned Parenthood representatives in class, some kids are getting condom-on-banana demonstrations in class, some kids are getting the chewed gum analogy, some kids are getting a lady John Oliver describes as “trying to yell the horniness out of teenagers,” some kids are getting exhaustive lists of sexually transmitted diseases without ever being taught what sex is or how it works or why humans have it in the first place. (LastWeekTonight 2015) Some kids are getting nothing at all.

What are we trying to prevent? Are we trying to prevent students having sex? Or are we trying to prevent early pregnancy, sexually transmitted diseases, sexual assault, and unhealthy sexual relationships? Abstinence-only education leans on the former even if under the guise of the latter. And while there is a strong philosophical case to be made that only the latter deserves a place in public education, extensive research shows that abstinence-only education is already failing at both. In 2014, the same Mississippi town that used the dirty chocolate classroom lesson reported that 76% of teenagers are sexually active while in high school, and that the local birthrate was 73 out of 1,000 females between 15 and 19: nearly triple the national rate at the time, which while declining, is still among the highest in the developed world. (Semuels 2014) (Holpuch 2016)

By contrast, a “comprehensive” sex education is set apart not only by medical accuracy but by inclusivity. While abstinence is technically medically accurate (yes, it is the only 100% effective way to prevent pregnancy and STIs), it omits much of the larger picture: the normalcy of sexuality in development, informed consent, contraceptive methods (especially those beyond the male condom), abortion, sexual pleasure, masturbation, forms of attraction, gender identity, sexual orientation, healthy relationships, and more. (Advocacy for Youth)

Ironically, the crux of the dilemma is that while CSE programs are elusive, support for them isn’t. National endorsement of CSE is overwhelming, not only among medical, scientific, and public health professionals, but also among education authorities, and even the American public. (SIECUS) So why is CSE so difficult to implement? The next sections explore attempts to enact and enforce CSE on various scales, and where this has been most effective.

Background: Attempts at Standardization

A 2015 editorial by Alice Dreger—writer, medical historian, bioethicist, and parent of a high-school boy—asked “Why isn’t sex education a part of Common Core?” Her question raises a confusing trend in national accountability: Common Core has embodied the huge push in national curriculum standardization, yet it only accounts for math and language, leaving other subjects relatively untouched. In some cases, Common Core’s emphasis on these two subjects has even had adverse effects on other subjects: in schools where standardized math/ELA test scores are low and budgets are increasingly skimpy, ‘non-core’ programs such as art, music, technology, physical education, vocational education, and health are often first on the chopping block to accommodate more time, money, and resources towards raising scores. In her article, Dreger advocates for consent and pleasure education to replace time spent on “endless lessons about how to put on a condom,” apparently not realizing how many American students won’t get condom education at all, much less consent or pleasure education. Oddly enough, she addresses the disparities in American sex ed twofold, both explicitly in her call for national standards, and implicitly in her ignorance of ‘how bad some other kids have it.’ (Dreger also gained media attention later that year for live-tweeting her son’s East Lansing, MI sex ed class, which featured abstinence-only speakers connected with a local anti-abortion “crisis pregnancy center.” (MLive 2015) The awareness she raised eventually pushed the school board to pull the religiously-affiliated speakers from their curriculum. (Culp-Ressler 2015))

Ultimately, Dreger’s article does more to advocate for why CSE should be nationally standardized than explain why it is not already. To answer this question, it’s necessary to delve into the history of sex ed standardization attempts, and examine the stark contrast between the drivers of Common Core and the drivers of nationalized CSE.

Though not remotely affiliated with Common Core, national sex education standards do exist, and they are comprehensive. “The National Sexuality Education Standards: Core Content and Skills, K-12” were released in 2012 by the Future of Sex Education (FoSE) Initiative, a “partnership between Advocates for Youth, Answer, and the Sexuality Information and Education Council of the U.S. (SIECUS).” They differ from Common Core in several key ways.

- Curriculum and tools for teachers are free, online, and open-sourced. FoSE’s website provides not only a detailed list of the standards for each grade, but a long list of tools for implementation that hone in on training teachers and other personnel (nurses, psychologists, etc.) and supplying administrators with templates to assist and evaluate budding CSE programs in their schools. (FoSE 2012) These tools are available to any teacher or school who wishes to access them, yet they require bottom-up self-implementation and enforcement. FoSE does not explicitly provide funding or personnel for teacher training, only written materials. By contrast, Common Core is implemented top-down in schools and classrooms. Teacher participation is mandatory, and both teacher and student performance is evaluated by national tests that the state has adapted.

- The stakes and accountability are different. Because of the personal and social nature of sexual education, it’s harder to track successful implementation in the same way. A math test generally gives a pretty good sense of what math a student knows and how they will use it in the real world. A sex education test, even if it measured what a student knew, wouldn’t necessarily provide any insight into how that student would make decisions in the future. (Given some of the abstinence-only programs we examined previously, it wouldn’t take a genius to figure out ‘sex is bad, don’t have it’ is they key to a high score on a test in an abstinence-only school.) While the stakes of both are high, sex education is more about social skills and personal health than competition and employability.

- The National Sexuality Education Standards were created by non-profits. These standards are crafted to be national but have no explicit federal government ties or endorsements. By contrast, Common Core is written by a coalition of states and incentivized as part of Obama’s federal Race to the Top program, and is surrounded by a wide support web (funding, public relations, content contributions) of state governments, third party companies, and prominent individuals. (Bernd 2013)

These three key differences shed light on the most important difference between NSES and Common Core, namely that the latter has been widely adopted by states, and the former hasn’t: unlike Common Core, states have essentially no tangible incentive—that is, financial incentive—to adopt NSES. While Common Core is tied to a bundle of federal carrots including Race to the Top grants and Title I funding for struggling schools, the non-profits that created NSES cannot fund the implementation of CSE standards, much less fund rewards for implementing CSE standards. (Kertscher 2013) (Ravitch 2016)

It’s no secret that the current federal administration’s views on public schooling, women’s rights, public health, gender, and sexuality make for a bleak outlook for federally-incentivized CSE; an administration that recently attempted to revoke transgender students’ Title IX protections in public schools is highly unlikely to support CSE that includes discussion of sexuality and gender identity in the first place. (Peters et al. 2017) There are some arguments to be made for how nonprofit coalitions like FoSE could incentivize implementation: perhaps by reorganizing spending to offer aid to districts implementing CSE, or to broaden their coalitions (maybe to include for-profit allies) to increase funds and support, or to emphasize how CSE could ultimately lower costs for states and schools (decreases in teen pregnancy and STIs could potentially lessen government funds spent on public assistance and state-subsidized health services.) However, perhaps in the name of efficacy, national standardization isn’t the necessary route at all: the next section will explore the pros and cons of alternatives.

Evidence: City-Based Public CSE Projects, Chicago as a Model

We find ourselves in search of a middle ground: good sex ed is so important that it can’t depend solely on the luck of a good teacher (a fictional 2014 movie popularized this narrative, placing a virginal straight white male teacher in a majority Latinx school to ‘save’ their sex ed program) but there’s also evidence to suggest that federally and nationally implemented standardization is neither probable, enforceable, nor measurably effective. City-led CSE reform just might be the middle ground that is needed to balance some level of large-scale standardization with small-scale implementation.

Chicago Public Schools (CPS), the third largest public school district in the continental US, has led the way in forging CSE reform at the city level. The Chicago Board of Education effectively implemented NSES in CPS in February 2013, with no clear catalysts or financial incentives at the time. (CPS Policy Manual 2013) By May 2013, House Bill 2675 mandating “medically accurate, developmentally and age-appropriate” Comprehensive Health Education was passed by the Illinois General Assembly, and eventually signed into law by Governor Quinn; prior to this, Illinois had not mandated teaching sex education at all, and when provided, mandated medical and moralized stress on abstinence. (NCSL 2016) By June 2013, the Chicago Dept. of Public Health (CDPH) published a policy brief in support of the recent city and state reforms, lending its support to the CPS CSE rollout and announcing a federal Teen Outreach Program (TOP) grant jointly awarded to CDPH and CPS for their cooperation in reducing teen pregnancy.

Chicago is a remarkable case study for several reasons. First: Chicago is a rare example of where NSES standards and trainings have been explicitly adopted in actual classrooms. Second: this reform occurred at a time when the federal government was in fact increasing spending for abstinence-until-marriage programs by $75 million a year. (de Melker 2015) Third, and most importantly: although Chicago’s CSE initiative eventually received state and federal reinforcements (both legally and financially), this reform was city and district-led. Only after the district policies were enacted did state law and federal dollars follow suit.

Chicago’s road to CSE reform hasn’t been an entirely smooth one; it hit its most public snafu in November 2014, after parents encountered material that detailed “the basics of female condoms,” “feel-good reasons to use them,” and “other forms of contraception, sex toys and sex acts” in CSE curriculum materials for fifth and sixth graders. CPS responded with, “The objectionable material presented at Andrew Jackson Language Academy this week is not and never was part of the student sexual education curriculum. It was mistakenly downloaded and included in the parent presentation, and we agree with parents it is not appropriate for elementary school students.” (NBC Chicago 2014) Indeed, most parents involved in the controversy supported CPS’ CSE reforms, but were largely concerned with the age-appropriate timing of material rather than CSE itself.

Improvement of the initiative may require some ‘tinkering towards utopia’ (to use a choice phrase in educational reform), but on the whole, response has been positive. In December 2014, CPS Sexual Health Program Assistant Maalika Bannerjee wrote: “Though there are hiccups, and progress can take time, it’s happening. Even I, coming from a liberal school in Massachusetts, didn’t have a chance to discuss gender identity or consent or healthy decision making in the classroom. By 2015, students in over 600 CPS schools will be able to do just that.” In distinct difference from the mistaken material, her accounts detailed activities that were far more commonplace in CPS schools as a result of the rollouts: for instance, a teacher-training exercise where participants had to describe their weekend without using gendered language. Bannerjee writes,

“There’s a pause. I notice some teachers begin sentences, and then stop. But after a few minutes, the conversations begin to flow. At the end, I ask them how it went. One gym teacher said he struggled with the activity. ‘I said ‘I’ a lot, and it felt really impersonal,” he said. Another person chimed in with some alternatives; he suggested the use of “they” in place of “he” or “she,” and “partner” or “significant other” in place of “boyfriend” or “girlfriend.” Another teacher said the activity helped her think about how difficult it is for some LGBTQ students, who may need to revise their language in school to avoid harassment from their peers. And yet another person said it made him think about using more inclusive language in the classroom, to make all students feel safe and comfortable at school.” (Bannerjee 2014)

Although Chicago’s 2015 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) data is not yet available to compare with 2013 data and gauge rollout effects, CPS has seen tangible positive impacts of the reforms in other ways. Some take the form of the classroom interactions like the one Bannerjee recorded above. Others take the form of student activism in the wider Chicago community. In December 2015, the Chicago Tribune reported on a 17-year-old CPS high schooler, Heaven Johnson, who partnered with the city’s Public Health Department to “launch a citywide safe-sex initiative that includes posters at CTA [metro] hubs and other parts of the city, a social media campaign (#ChicagoWearsCondoms) and volunteers periodically handing out free condoms.” Johnson’s efforts are quite literally seen all over the city, and her website directs citizens to “169 locations around Chicago that distribute free condoms, as well as addresses, phone numbers and hours for facilities that provide free sexually transmitted infection and HIV testing and treatment.” (Stevens 2015)

Conclusion

As with any policy model, city-led CSE reform is not proposed as a catch-all panacea to rescue America from sex ed’s victimization at the state and federal level. Some locations prove more difficult than others: for instance, in New Orleans, city-led CSE proposals faced similar roadblocks and backlash from the state level as state-led CSE proposals. (O’Donoghue 2015) Some locations don’t have the luxury of a school board large enough to encompass many schools nor formidable enough to spar with conservative municipal governments: persistent advocacy is still needed at the state level, especially to make sure rural students don’t ‘fall through the cracks’ of CSE reform.

However, I present the Chicago model as an exciting case where national CSE standards are actually starting to reach classrooms and have a positive impact on students as a result of localized bottom-up action. Despite initial state and federal resistance, Chicago’s great strides in CSE represent not only the potential of American cities, but indeed of public schools.

[Word Count: 3469]

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to peer editors Eliza Scruton and Molly Ono.

Works Cited

Advocates for Youth. Sex Education Programs: Definitions & Point-by-Point Comparison. Retrieved from http://www.advocatesforyouth.org/publications/publications-a-z/655-sex-education-programs-definitions-and-point-by-point-comparison

American Federation for Children. (2015, March 13.) Betsy DeVos SXSWedu. [Video file.] Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f_2nH4aLLDc&feature=youtu.be

Bannerjee, M. (2014, December 30.) Taking Pride in Progress: Implementing Sex Ed in Chicago. Retrieved from http://nhc.networkforchange.org/chicago/blog/taking-pride-progress-implementing-sex-ed-chicago

Bernd, C. (2013, September 6.) Flow Chart Exposes Common Core’s Myriad Corporate Connections. Retrieved from http://www.truth-out.org/news/item/18442-flow-chart-exposes-common-cores-myriad-corporate-connections

beyonceVEVO. (2014, November 24) Beyoncé – ***Flawless ft. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. [Video file.] Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IyuUWOnS9BY

Chicago Department of Public Health. (2013, June.) SEXUAL EDUCATION POLICY IN ILLINOIS AND CHICAGO. Retrieved from https://www.cityofchicago.org/content/dam/city/depts/cdph/CDPH/HCPolicyBriefJune2013.pdf

Chicago Public Schools Policy Manual. (2013, February 27.) Title: SEXUAL HEALTH EDUCATION; Section: 704.6; Board Report: 13-0227-PO1. Retrieved from http://policy.cps.edu/download.aspx?ID=57

Culp-Ressler, T. (2015, April 21.) One Woman Live-Tweeted Her Son’s Abstinence-Focused Sex Ed Class. Now Things Might Change. Retrieved from https://thinkprogress.org/one-woman-live-tweeted-her-sons-abstinence-focused-sex-ed-class-now-things-might-change-415fdd10b6e6

de Melker, S. (2015, May 27.) The case for starting sex education in kindergarten. Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/newshour/updates/spring-fever/

Dreger, A. (2015, February 27.) Why Isn’t Sex Education a Part of Common Core? Retrieved from https://psmag.com/why-isn-t-sex-education-a-part-of-common-core-4a5b1a4deb7f

FoSE. (2012.) National Sexuality Education Standards. Retrieved from http://www.futureofsexed.org/nationalstandards.html

FoSE. (2012.) The National Teacher Preparation Standards for Sexuality Education: Tools for Implementation. Retrieved from http://www.futureofsexed.org/implementation.html

Guttmacher Institute. (2017, May 1.) Sex and HIV Education. Retrieved from https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/sex-and-hiv-education

Holpuch, A. (2016, September 28.) US teenage birth rates fall again but still among highest in developed world. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/sep/28/us-teenage-birth-rates-fall-again

Kertscher, T. (2013, October 24.) How much is the federal government involved in the Common Core school standards? Retrieved from http://www.politifact.com/wisconsin/statements/2013/oct/24/sondy-pope/how-much-federal-government-involved-common-core-s/

Klein, R. (2014, April 8.) These Maps Show Where Kids In America Get Terrifying Sex Ed. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/04/08/sex-education-requirement-maps_n_5111835.html

Labaree, D. (1997.) Public Goods, Private Goods: The American Struggle over Educational Goals. American Educational Research Journal 34(1):39-81.

LastWeekTonight. (2015, August 9.) Sex Education: Last Week Tonight with John Oliver (HBO). [Video file.] Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L0jQz6jqQS0&pbjreload=10

Leip, D. (2016.) 2016 Presidential General Election Results. Retrieved from http://uselectionatlas.org/RESULTS/national.php

MLive. (2015.) Author tweets sex ed course at East Lansing school. Retrieved from https://storify.com/MLive/author-tweets-sex-ed-course-at-east-lansing-school

Moviclips Trailers. (2014, October 11.) Sex Ed Official Trailer #1 (2014) – Haley Joel Osment Movie HD. [Video file.] Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j2vmzw9GjEo

National Conference of State Legislatures. (2016, December 21.) STATE POLICIES ON SEX EDUCATION IN SCHOOLS. Retrieved from http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-policies-on-sex-education-in-schools.aspx

NBC Chicago. (2014, November 14.) Parents Shocked by Material in Presentation on School’s New Sex Health Curriculum. Retrieved from http://www.nbcchicago.com/news/local/Parents-Shocked-by-Material-Mistakenly-Included-in-Presentation-on-Schools-New-Sex-Health-Curriculum-282788211.html

The New York Times. (2016, October 8.) Transcript: Donald Trump’s Taped Comments About Women. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/08/us/donald-trump-tape-transcript.html?_r=0

O’Donoghue, J. (2015, May 19.) New Orleans doesn’t get the sex education curriculum it wants. Retrieved from http://www.nola.com/politics/index.ssf/2015/05/new_orleans_sex_education_abst.html

Peters, J., Becker, J., & Hirschfield Davis, J. (2017, February 22.) Trump Rescinds Rules on Bathrooms for Transgender Students. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/22/us/politics/devos-sessions-transgender-students-rights.html

PhilanthropyRoundtable. (2013, Spring.) Interview with Betsy DeVos, the Reformer. Retrieved from http://www.philanthropyroundtable.org/topic/excellence_in_philanthropy/interview_with_betsy_devos

Planned Parenthood Federation of America. (2011, October 3.) New Poll: Parents are Talking With Their Kids About Sex but Often Not Tackling Harder Issues. Retrieved from https://www.plannedparenthood.org/about-us/newsroom/press-releases/new-poll-parents-talking-their-kids-about-sex-often-not-tackling-harder-issues

Planned Parenthood Federation of America. (2012, October 2.) Half of All Teens Feel Uncomfortable Talking to Their Parents About Sex While Only 19 Percent of Parents Feel the Same, New Survey Shows. Retrieved form https://www.plannedparenthood.org/about-us/newsroom/press-releases/half-all-teens-feel-uncomfortable-talking-their-parents-about-sex-while-only-19-percent-parents

Ravitch, D. (2016, January 22.) EXCLUSIVE: How Does ESSA Affect Opt Outs? Part 4. Retrieved from https://dianeravitch.net/2016/01/22/exclusive-what-does-essa-affect-opt-outs/

Semuels, A. (2014, April 2.) Sex education stumbles in Mississippi. Retrieved from http://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-ms-teen-pregnancy-20140403-story.html

Shuger, L. (2012.) Teen Pregnancy & High School Dropout. Retrieved from https://www.americaspromise.org/sites/default/files/legacy/bodyfiles/teen-pregnancy-and-hs-dropout-print.pdf

SIECUS. Who Supports Comprehensive Sexuality Education? Retrieved from http://www.siecus.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=Page.ViewPage&PageID=1198

Stevens, H. (2015, December 3.) Chicago (and its skyscrapers) wear condoms, thanks to new campaign. Retrieved from http://www.chicagotribune.com/lifestyles/stevens/ct-chicago-wears-condoms-campaign-balancing-20151203-column.html

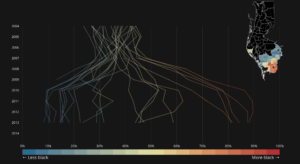

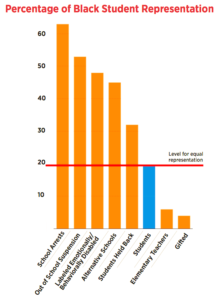

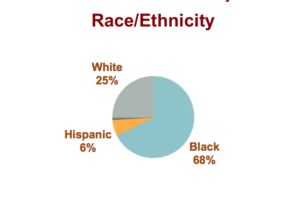

Figure 1: This shows the proportion of black students in Pinellas County schools prior to and post 2007. The map in the top right corner displays Pinellas County, showing that the mostly black schools are heavily concentrated in the southernmost part of the district.

Figure 1: This shows the proportion of black students in Pinellas County schools prior to and post 2007. The map in the top right corner displays Pinellas County, showing that the mostly black schools are heavily concentrated in the southernmost part of the district.

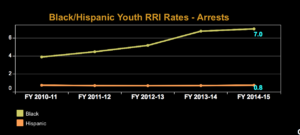

Figure 8: The growing Relative Rate Index shows that racial disparities in school arrests and the juvenile justice system are increasing.

Figure 8: The growing Relative Rate Index shows that racial disparities in school arrests and the juvenile justice system are increasing.

Source:

Source: