Otis Baker Professor Mira Debs EDST 245: Public Schools and Public Policy 5/3/2017

Introduction

People often attribute the achievement gap between boys and girls to learning differences between the sexes [1]. One way educators address these differences is by placing boys into single gender classrooms. An all-boys school is seen as a way to tailor education to the specific learning needs of boys. According to the UCLA Center for Mental Health in Schools, all-boys schools do provide advantages. They make boys less competitive, and more collaborative. The report also concludes that all-boys schools are better at providing same gender role models and makes for a less distracting learning environment [2]. All-boys schools have the ability to reverse educational trends for males, especially in environments where they may have more distractions or fewer role models.

In New Haven, Dr. Boise Kimber believes so. Dr. Kimber believes that such an environment could help young Black boys in New Haven achieve more than the current education statistics show. He has recently proposed an all-boys school, focused on young men of color in New Haven. There are now strong factions in support of Dr. Kimber and his plan as well as factions in opposition. After analyzing his plan to help these students and then evaluating his model, I believe Dr. Kimber’s plan is certainly noble and deserves its desired funding. However, based on the results of its model schools any future plan should include strong measures for accountability of the academy.

The State of Current Affairs

In 2013, the state of Connecticut published a report boasting about the current status of education in Connecticut. It highlighted that higher percentages of students were graduating high school than in years past.

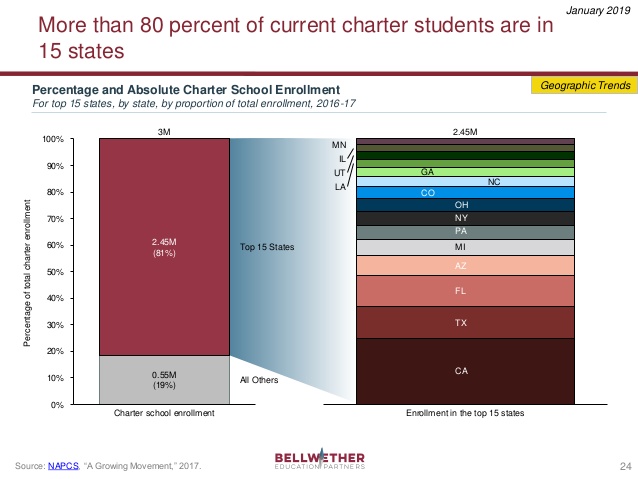

Figure 1: Chart compares state vs. district graduation rates for specific groups

The report boasted an 84% graduation rate for all students, a 2.1% increase from 2011. The rate of graduation for Black students in Connecticut was 73%, a 1.3% increase [3]. This report was encouraging but misleading. The city of New Haven fell significantly short of the rest of the state. In the fine print (a link to the rest of the data) the survey provided the graduation rate for students in New Haven. In the Elm City, 70% of all students graduated, 14% lower than Connecticut at large. While the rest of the state might be improving, New Haven is falling behind. The discrepancy between the district and the state was not even across all student student groups. There were small reductions in the rates of graduation for Asian and white students, but the largest change was in male students vs. female students. The state graduation for males in Connecticut is nearly 82%. In New Haven, that rate for males drops to 63%, an alarming 19% decrease [4]. The drop for females in New Haven is only 10% below females statewide. In terms of Black males, the graduation rate in the state of Connecticut is 53% [5]. The datas show two trends. New Haven is significantly behind the state in education. And, the ones suffering the most are Black males.

There are several possible explanations for why male students in New Haven are suffering. One of the principal explanations is that Black males are poorly represented in the teacher force. In 2013, of 1,883 teachers in the New Haven school district, only 56 of them were Black males. The New Haven district students are 42% Black and 41% Hispanic [6]. There is a mismatch between the number of minority male students in New Haven and the number of minority male teachers. The potential implications of this gap extend beyond simply having a diverse workforce. Young Black and Hispanic males have fewer teachers that they can view as role models who look like them. A Johns Hopkins report found that young Black boys that have at least one black teacher from grades 3-5 have a 39% lower chance of dropping out of high school. The study also discovered that these same boys have a 29% increase in college matriculation.[7] Black students, especially young Black males benefit immensely from having Black teachers as role models. One teacher interviewed for Through Our Eyes, a study on Black teachers, offers an explanation: “I think we don’t have the trust barrier sometimes that other teachers of a different ethnicity may” [8]. Black students, especially males, benefit from having a trusted advisor with shared experiences. This trust translates to students being more willing to engage in and out of the classroom as well. In New Haven, there is a substantial shortage of Black Male teachers, which is likely a primary contributor to the lower graduation rates of Black male students.

Violence is a contributor to the lower graduation rates of Black males. In 2013, of the 20 homicides that occurred in New Haven, 9 of the victims were between 18-23 years old.[9] Of these 20 homicides, 17 of the victims were Black. Though these victims were just beyond the age of high school graduation, the evidence shows that violence is prevalent around young males in New Haven. Gun Violence in these urban areas distracts students from their studies. Obviously, gun violence can result in traumatic experiences. But it can also create an atmosphere of hyper alertness, making students stress about details like their route to school [10]. This violence can lead many away from school and often into destructive behaviors and pursuits. Spending time in juvenile detention lowers the rate of high school graduation by 13% according to a study by MIT [11]. The prevalence of violence and crime in New Haven magnifies the need for more guidance, structure, and mentorship to keep young males away from crime and in school.

Dr. Kimber’s Proposed Solution

Dr. Boise Kimber, a pastor at the First Calvary Baptist Church in New Haven, first envisioned an all-boys school for young Black men in New Haven in 2007. He had become extremely concerned with the opportunities and paths laid out for young men of color in his larger community [12]. He knew that as the achievement gap between Blacks and Whites in New Haven schools grew, too many Black boys were being left behind, dropping out of school, and turning to lives of crime or unemployment. He saw that there was a lack of mentorship for boys of color and a dearth of educators who looked like them. Dr. Kimber felt that these factors were all intertwined. So, he decided that he wanted to create a school that could do something about it. He told an interviewer that he, “wanted to create an environment where boys of color in New Haven could participate in a structured environment where they could learn to become young men. Young men with a purpose. Young men being men in this 21st century.” Kimber’s vision manifested itself into what he called C.M. Cofield Academy [13].

Kimber envisioned C.M. Cofield Academy as a school that would serve at-risk boys of color in New Haven. He wanted to model the school after the mission of Morehouse College, the historically Black Men’s college in Atlanta: “to develop men with disciplined minds to lead lives of leadership and service by emphasizing the intellectual and character development of its students and by assuming a special responsibility for teaching the history and culture of black people.”[14] The all-boys school would have a strict uniform policy, and it would focus on teaching both academics and values like responsibility and discipline. Kimber’s school would also have predominantly Black male teachers, providing an image of role models who are positive contributors to their community and beyond. When Kimber originally proposed the school, he wanted to make it a state-funded charter school. The New Haven Board of Education (BOE) rejected his original proposal citing “too many charters” as the reason for its failure. Kimber has now returned to the BOE several times with different elements to the proposal. He has achieved a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the New Haven division of the American Federation of Teachers to build the school and has now proposed it as an inter-district charter run by the New Haven BOE, the first of its kind in New Haven. Kimber is modeling the structure of the school on Eagle Academy, which operates six all-boys schools of predominantly boys of color in and around New York City. These schools focus on mentorship for at-risk youth and work to achieve many of Kimber’s same goals [15].

Many of the modifications Kimber has made to his proposal are specifically to gain Board approval and move forward. He plans to start with approximately 60-80 students, divided into just 4 classrooms. He claims that the school will not require the construction of any new building, but rather will utilize rented space. This means that the school would likely not require any “new” funding. Instead, Kimber and his supporters propose that the district redirect existing education dollars to fund the school. Ultimately, Kimber hopes that the board will approve his proposal and hire an outside consultant to formalize a partnership between C.M. Cofield and the Eagle Academy Network. This would finally grant him a contract of education, making the C.M. Cofield Academy official [16]. There are several members of the BOE currently in opposition to Dr. Kimber’s proposal. The biggest obstacle for the plan is a question of per student funding. Because C.M. Cofield plans on being an inter-district charter, monitored by the New Haven BOE, it cannot receive per student state funding. Instead, the New Haven school district must pay for each student. This would be a smaller problem if Kimber didn’t insist on the policy of accepting students from other districts. The BOE is hesitant to accept a proposal for where the New Haven taxpayers would have to pay for other district’s students [17]. However, Kimber still contends that opposition from the BOE is personal, not because board members believe that the plan fails to help close the achievement gap in New Haven. However, Kimber also has some supporters for the school. Mayor Toni Harp has endorsed the idea. She believes that the BOE should have an open mind on different ways of addressing the achievement gap.[18] Kimber expects that with the election of two new BOE members, the proposal will finally be approved in January of 2018.

Eagle Academies and the Model

The original Eagle Academy was founded in 2004 in the South Bronx. The school was founded by the 100 Black Men of America group and David Banks, who now serves as the president of the Eagle Academy Foundation. The group’s mission is to improve conditions for young Black men in their communities with the motto “what they see is what they’ll be” [19]. Banks and the group set up the school with the belief that boys learn differently than girls and need more guidance and mentorship, especially in at-risk communities. The original Eagle Academy then spawned the creation of several other Eagle Academies around New York City, as well as one in Newark, New Jersey.

The schools have several general practices that push these goals forward. The Eagle Academies aim to create a strong sense of brotherhood through unique traditions and rituals. The students at Eagle Academies attend town hall meetings each morning where they discuss current issues in their community and beyond. They close each of these meetings with “libations” where boys water a tree and give thanks to people in their life. Finally they all recite William Ernest Henley’s Invictus before the start of classes.[20] The students also compete in academics and service through a “house” system. Students earn points for their house by achievement in and out of the classroom. These all contribute to the school’s goal of creating brotherhood.

Eagle Academies also work to foster significant parent involvement with schooling. Each school has a parent liaison that is a full time employee dedicated to helping parents understand what is going on at school and explaining how they can help their sons. Two other key elements to the Eagle Academies’ approach are early college preparation and Black male teachers who come from the business world. Early college preparation for Eagle Academy students sets forth goals to work towards. Having these specific goals makes it more likely that the students continue their education after high school. But arguably the most important feature at Eagle Academies is the presence of strong black male role models for the students. The Eagle Academies believe that the young men of color need to see the world of possibilities through strong Black male mentors. These mentors inspire the students to believe that these positions in society and in their community are not just possible for them, but expected of them [21].

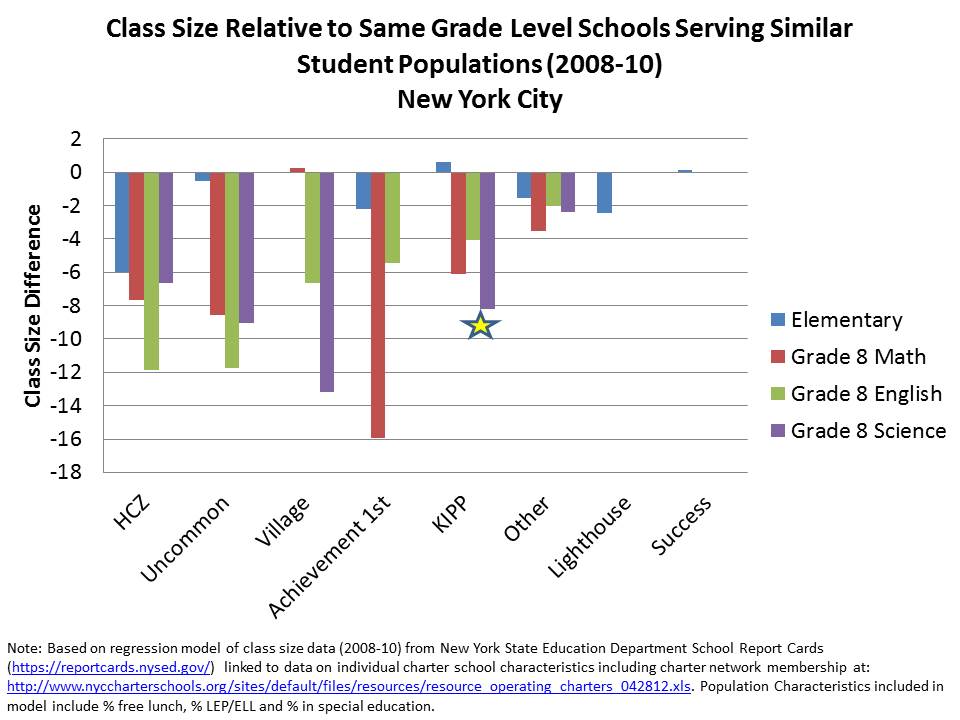

The mission of Eagle Academies is rosy, but in practice many of the results of the school are not as inspiring. In a survey provided to all parents and teachers in the New York Public School system, Eagle Academy often scored lower than its surrounding borough, the Bronx, and the citywide average. Eagle Academy received only a 70% positive rating for rigorous instruction while the borough and city averages were 79% and 81%, respectively [22]. Eagle Academy’s reviews on providing a supportive environment were even more concerning than their ratings academic for rigor. Supposedly a key component of the school, only 63% of survey respondents believed the school provided an adequately supportive environment in which its students could achieve. This number was also lower than the borough and city averages. Graduation rate was the one area where the school had more success. Eagle Academy was able to graduate 79% of students compared with a 70% graduation rate of schools in similar environments. Eagle Academy also beat the borough and city graduation rate averages. A concerning corollary to this graduation rate statistic is that of the Eagle Academy graduates, only 12% passed a college preparedness examination. Surrounding schools serving similar demographics averaged 25% [23].

Figure 2: Eagle Academy statistics compared to NYC counterparts

The primary conclusion that this data suggests is that Eagle Academies are not academically rigorous. This could be a result of prioritizing keeping students in school rather than discouraging students by having them fail. The other troubling conclusion is that the reviews of the school environment were not overwhelmingly positive. This might not be a structural problem with Eagle Academies and their mission, but rather a problem of leadership and personnel. Regardless, it is concerning that the school is not able to definitively achieve one of the initiatives that it cites as a primary goal.

Conclusion

It is impossible to argue that Dr. Kimber’s vision is not a noble one. He believes in young Black men, and he believes in creating a system through which they are placed on a better path to succeed. However, it is still unclear whether the C.M. Cofield Academy, as proposed, is the best way to achieve that. The potential pitfalls of Kimber’s plan are many. The Eagle Academy model shows that while Kimber’s school could succeed in its goal of engaging young men of color and keeping them in school, it is possible that the students remain unprepared for college or other secondary education. Kimber also could have difficulty attracting Black men from the business world, an essential element of the mentorship component in the Eagle Academy model.

C.M. Cofield Academy has many advantages over its intended model, the Eagle Academies. Kimber’s school, as it is currently proposed, aims to serve a small group of students. Therefore, Kimber would have to find fewer exemplary Black male teachers. The smaller scale would also make it easier for administrators and the Board of Education in New Haven to monitor the school. C.M. Cofield could be accountable for its smaller number of students and work at a micro level to make a strong impact on the at-risk young men of New Haven.

To close, I would make the following policy recommendation: I would approve Dr. Kimber’s plan for C.M. Cofield Academy. However, I would place strict accountability policies on the school for academic rigor. I would also place the school on a trial program that grants them a conditional contract for education for 4-5 years, at which point the Board of Education re-evaluates the school’s contract. I think Kimber’s plan could make a significant impact on a the young males of New Haven, but it needs to proceed with the proper accountability measures placed on both academic achievement and on C.M. Cofield Academy’s adherence to Eagle Academy’s focus on mentorship for at-risk boys.

Footnotes:

- National Education Association.Research spotlight on single-gender education

- Yayang Xiong, C.Single sex education.

- CT Department of Ed. (2015). Connecticut 2014 cohort graduation rate

- Ibid.

- John, P. (2015). The schott 50 state report on public education and black males.

- Bailey, M. (2013, ). Out of 1,883 teachers, 56 black males. New Haven Independent

- Rosen, J. (2017). Black students who have at least one black teacher are more likely to graduate.

- Griffin, Ashley and Hilary Tackie. 2016. Through Our Eyes: Perspectives and Reflections From Black Teachers. Education Trust.

- Ortiz, J. (2016, ).New haven homicides and shooting down in 2016. New Haven Register

- Quick, K. (2016).Gun violence puts education under fire, stifling achievement. Retrieved fromhttps://tcf.org/content/commentary/gun-violence-puts-education-under-fire-stifling-achievement/

- Dizikes, P. (2015). Study: Juvenile incarceration yields less schooling, more crime.

- Baker, O. (2017). Interview with Dr. Boise Kimber

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Bass, P. (2017, ). Kimber swings back at school critics.New Haven Independent

- Baker, O. (2017). Interview with Dr. Boise Kimber

- 100 black men of america. (2017). Retrieved from http://www.100blackmen.org/

- Eagle Academy Bronx. (2016). Traditions. Retrieved from https://sites.google.com/eaglebronx.org/eagle/about-eagle/traditions

- Ibid.

- NYC Dept. of Education. (2016). 2015-16 school quality snapshot.().NYC DOE.

- Ibid.

References

100 black men of america. (2017). Retrieved from http://www.100blackmen.org/

Bailey, M. (2013, ). Out of 1,883 teachers, 56 black males . New Haven Independent

Baker, O. (2017). Interview with dr. boise kimber

Bass, P. (2017, ). Kimber swings back at school critics. New Haven Independent

CT Department of Ed. (2015). Connecticut 2014 cohort graduation rate. ().

Dizikes, P. (2015). Study: Juvenile incarceration yields less schooling, more crime. Retrieved from http://news.mit.edu/2015/juvenile-incarceration-less-schooling-more-crime-0610

EAFNY. (2016). The eagle academy foundation. Retrieved from www.eafny.com

Eagle Academy Bronx. (2016). Traditions. Retrieved from https://sites.google.com/eaglebronx.org/eagle/about-eagle/traditions

Liu, M. (2017, ). Kimber’s charter sparks creed backlash. New Haven Independent

National Education Association.Research spotlight on single-gender education. Retrieved from http://www.nea.org/tools/17061.htm

NYC Dept. of Education. (2016). 2015-16 school quality snapshot. ().NYC DOE.

Ortiz, J. (2016, ). New haven homicides and shooting down in 2016. New Haven Register

Quick, K. (2016). Gun violence puts education under fire, stifling achievement. Retrieved from https://tcf.org/content/commentary/gun-violence-puts-education-under-fire-stifling-achievement/

Rosen, J. (2017). Black students who have at least one black teacher are more likely to graduate. Retrieved from https://hub.jhu.edu/2017/04/05/black-teachers-improve-student-graduation-college-access/

St. John, P. (2015). The schott 50 state report on public education and black males.

Yayang Xiong, C.Single sex education. ().UCLA Center for Mental Health in Schools.

Zahn, B. (2017, ). New haven board of education discusses proposal for public all-boys school. New Haven Register