Introduction

In 2015, “Failure Factories,” a Tampa Bay Times exposé on the failure of hyper-segregated south county elementary schools called Pinellas County “the worst place to be black and attend public schools in Florida.”

After a 2007 decision by the school board to abandon integrative busing measures, five elementary schools in a small, historically black area of the southern part of the county quickly became five of the worst schools in Florida. Since 2015, the series “Failure Factories” won a Pulitzer Prize in local reporting, a new superintendent was hired, the federal government launched a civil rights investigation into the district’s practices, and black students in Pinellas are no better off.

Indeed, the effects of hyper-segregation soon bled into every facet of the school system, including disciplinary measures that increasingly began to affect black students at a widening, disproportionate rate (National Juvenile Justice Network 2015, and Florida Department of Juvenile Justice 2015).

Analysis of Pinellas County discipline records show that black students are more likely than their white peers to face in-school-suspension, out-of-school suspension, and school arrests (National Juvenile Justice Network 2015). I plan to argue that the racial disparities seen in disciplinary practices and the 2007 decision to end busing efforts have contributed to the racial achievement gap in Pinellas County Schools.

I will then analyze data from the eighth worst performing school in Florida, Campbell Park Elementary, tracking changes to academic performance following resegregation. Although I will not attempt to prove causality, the unique plight of south county schools cannot be explained by factors like poverty as these schools are performing worse than schools in districts with fewer resources (Bureau of Economic Analysis 2006).

Finally, I will consider literature that suggests these factors are disproportionately harming black students in Pinellas. Other reports have studied the achievement gap and disciplinary disparities in Pinellas County but none have discussed the intersection of these as a direct result of the 2007 to stop integrative busing.

Background

As is common across the nation, Pinellas County Schools has struggled to integrate schools since Brown v. Board due in large part to the unequal demographic makeup of the district neighborhoods (Rothstein 2014). School enrollment data shows that 55.9% of students are white, 18.6% are black, and 16.4% percent are Hispanic (Pinellas County Schools 2016). However, black students in Pinellas are concentrated in the southern part of the county so much so that 85% of African American families live within a 12-square-mile section in St. Petersburg, the fourth largest city in the state of Florida (Fitzpatrick, Gartner, & LaForgia 2015, DeBray 2007). Julie Janssen (2001) describes the unique demographic pattern:

This school district has specific and unique geographical politics, stemming in part from the division of the County into north and south by Ulmerton Road. The racial composition of students in the two geographic regions are notably dissimilar with the majority of black students living in the southern part of the district and only small “pockets” of black students living north of the dividing line, Ulmerton Road. (p. 13)

This pattern is longstanding and the racial makeup of the district looked similar in 1971, when the court decision Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg (1971) forced the school district to implement busing to integrate the county (DeBray 2007). This court ordered busing was for all intents and purposes effective. In 1976, only 3.8% of black students went to majority African American schools whereas 54.5% of black students had gone the majority African-American schools in 1970, prior to the Swann decision (DeBray 2007).

The 1971 court order also laid out enrollment limits that stated no school would exceed 30% African American students (later changed to 42% for the 2003-2004 school year) (DeBray 2007).

Yet this 1971 plan to begin busing in Pinellas County was implemented in such a way that the predominantly white residents in the northern part of the county were excluded from the orders. And so, black students south of the Ulmerton road divide were bused outside of their neighborhood to achieve racial diversity (DeBray 2007).

Understandably, black residents spoke out against this inequity and in 1998 the plan for school choice was revisited. Families across the county and the local National Association for the Advancement of Colored People chapter met with the School Board, which then voted to ask the U.S District Court for a unitary designation for the county, essentially freeing the district from the court order laid out in Swann. This was done in hopes of developing a method for voluntary choice that would put a stop to the unfair treatment of families in the south county neighborhoods (DeBray 2007).

The district court ruled in favor of the unitary distinction, allowing the county to develop a method of choice integration so long that it complied with the previous limits of racial makeup for individual schools. Choice “zones” were created and so long as families made choices that adhered to the racial makeup limitations, their choices were granted. Additionally, students in north county were no longer exempt and thus busing became more equitable across the county (DeBray 2007).

In 2007, the Parents Involved vs. Seattle School District Supreme Court case ruled that schools could no longer control enrollment by race. This decision meant the end of the practice of obligatory racial proportions that Pinellas County and other districts across the national had been using to balance diversity within the county. So, in 2007 the Pinellas County School Board voted to end integrative busing. Families across the country rejoiced that their children would no longer have to commute 30-45 minutes to a school outside of their residential neighborhood. But black community members were not as pleased and voiced concerns that the predominantly black neighborhoods in southern county would suffer for these changes. The district ensured that the quality of the schools would not falter, promising extra funding and resources that never came (Tampa Bay Times Staff 2007, and Fitzpatrick, Gartner, and Laforgia 2015).

Thus, the hypersegregation of Pinellas County began.

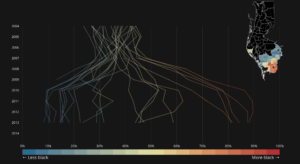

Figure 1: This shows the proportion of black students in Pinellas County schools prior to and post 2007. The map in the top right corner displays Pinellas County, showing that the mostly black schools are heavily concentrated in the southernmost part of the district.

Figure 1: This shows the proportion of black students in Pinellas County schools prior to and post 2007. The map in the top right corner displays Pinellas County, showing that the mostly black schools are heavily concentrated in the southernmost part of the district.

Academic Failure after Resegregation

The decision to end busing turned out to be a disastrous one for black families in Pinellas County. Resources were not funneled to schools in historically black neighborhood schools as was promised. Instead, the district used shady tactics to attempt to shortchange south county schools from their district funding, counting money received from the federal Title I allotment towards their district budget total (Fitzbatrick, Garter, and Laforgia 2015).

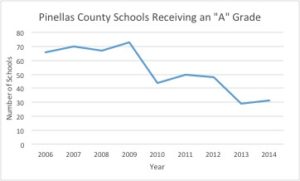

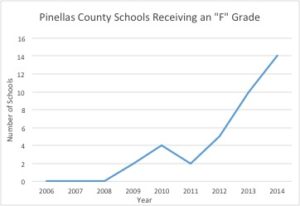

It didn’t take long for the effects of implementation to negatively impact school performance. The state of Florida uses a grade-based accountability system to evaluate each of its schools at the end of the academic year. Schools are measured by metrics including performance on state standardized tests but also learning gains for all students and for the lowest performing 25% of students. Academic outcomes in Pinellas County took a dive across the district after 2007. The charts below show the number of Pinellas County Schools that received an “A” on Florida’s annual school grading system and the number that received an “F”.

Figure 2: The number of schools receiving an A grade on the annual accountability report dropped after 2007.

Figure 3: The number of schools receiving an F grade on the annual accountability report rose from 0 schools to 14 schools in just six years.

Source: Florida Department of Education. School Accountability Reports 2006-2014.

Academic Inequality

Even though Pinellas County showed a decline across all schools’ performance after 2007, it was the south county schools that felt the brunt of the impact. Without the resources that the white, north county students brought to the south county schools, the schools quickly became some of the worst in Florida (Fitzpatrick, Gartner, LaForgia 2015).

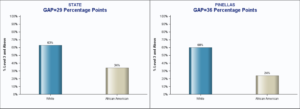

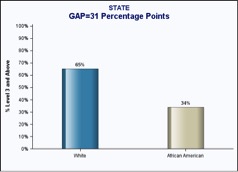

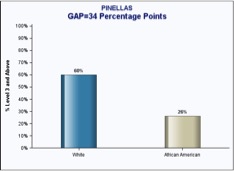

And since the southern county schools are predominantly black, a pronounced black-white racial achievement gap emerged in Pinellas County. Testing results from Florida standardized tests administered to all student in the 2015-2016 school year are shown below.

Figure 4

Pinellas County boasts an achievement gap between their black and white students that is markedly higher than state averages in both English Language Arts and Mathematics

Figure 4.1: The achievement gap in Pinellas County (right) as compared to state averages (left) in English Language Arts. Florida Department of Education. 2015-2016

Figure 4.2: The achievement gap in Pinellas County (right) as compared to state averages (left) in Math. Florida Department of Education. 2015-2016

A Case Study

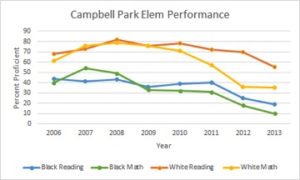

In 2007, prior to resegregation in Pinellas, Campbell Park Elementary was a “B” school with a school population of 32.8% white students and 47.8%. By 2015, Campbell Park had become segregated with a population made up of 13.6% white students and 79.9% black students. It was consistently receiving an “F” grade on its annual accountability report (Florida Department of Education).

Here, I track Campbell Park’s decline from an average elementary school to one of the worst in the state. This decline took place in the years following the 2007 decision to abandon busing. The school quickly became hyper-segregated, lost teachers, saw an unprecedented increase in violent incidents and exclusionary discipline practices (Fitzpatrick, Gartner, and LaForgia 2015).

Figure 5: While academic achievement suffered across the board at Campbell park, the black-white achievement gap perisisted, with only 20% and 10% of black students being proficient in reading and math respectively in 2013.

While each of the aforementioned factors can independently cause students at a school to suffer losses in academic performance, the decline at Campbell Park Elementary was unparalleled by any other school in Florida. In fact, schools in communities with the same racial and socioeconomic makeup were not performing as badly as Campbell Park (Fitzpatrick, Gartner, and LaForgia 2015).

Discipline in Pinellas County

On the Pinellas County School Board website, it states that “In all instances, school discipline should be reasonable, timely, fair, age-appropriate, and should match the severity of the student’s misbehavior.” And for some students, this might hold true. However, investigation into county discipline records shows that black students are disproportionately on the receiving end of disciplinary practices, and to a greater degree than their white peers.

Compared to the State

Pinellas County boasts an unusually high number of suspensions. In fact, Pinellas County employs suspension as punishment more often than 70% of the other counties in Florida (National Juvenile Justice Network 2015).

Similarly, Pinellas has a high rate of school arrests, recording a higher number of school arrests for 2015 than 81% of counties in Florida (National Juvenile Justice Network 2015).

Racial Disparities

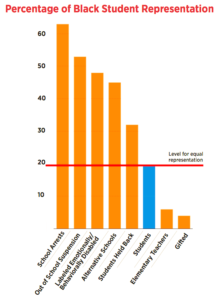

While these numbers alone should be enough to make Pinellas officials pay attention to the district’s disciplinary problems, the underlying racial disparities taking place in all facets of school discipline are even more concerning.

- 54% of black students received an in-school suspension compared to 20% of their white peers

- Pinellas is 3rd in the state for disproportionately arresting black students

While 20% of the students in Pinellas County are black, black students are overrepresented in the number of school arrests, out-of school suspensions, number of students labeled “Emotionally/Behaviorally Disabled”, number of students held back a grade, and the number of students sent to an alternative school. Black Pinellas students are underrepresented in gifted classrooms. Moreover, only 8% of Pinellas County teachers are black, 12 points below the proportion of black students and nearly half the state average (National Juvenile Justice Network 2015).

Figure 6: Black students are overrepresented in discipline numbers and special needs classrooms and underrepresented in the teaching force and gifted classrooms.

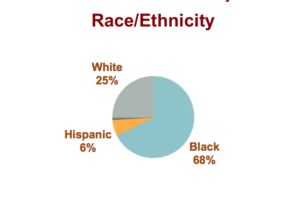

Furthermore, black students in Pinellas represent 68% of the students arrested for school related incidents.

Figure 7: Even though black students comprise less than 20% of students enrolled in Pinellas County schools, they make up almost 70% of school arrests.

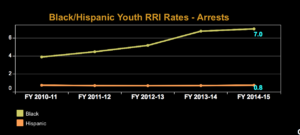

And despite a downward 5-year trend of school arrests in Pinellas County, the county’s Relative Rate Index, a measure used to compare arrests of black juveniles versus white juveniles has been steadily increasing since 2010 (Florida Department of Juvenile Justice 2015).

Information gathered in the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice Disproportionate Minority Contact Benchmark report for the FY 2014-2015 measures the occurrences of juvenile interaction with the juvenile justice system. A Relative Rate Index score of 1.0 indicates that the rate of occurrence for white juveniles is the same as the rate of occurrence for minority juveniles. An RRI score greater than 1 indicates that the rate of occurrence is higher for minority juveniles than white juveniles, and vice versa for a RRI score less than 1.

Pinellas County has an RRI score of 6.2, making it the 4th highest in the state.

Figure 8: The growing Relative Rate Index shows that racial disparities in school arrests and the juvenile justice system are increasing.

Figure 8: The growing Relative Rate Index shows that racial disparities in school arrests and the juvenile justice system are increasing.

Explanations

While I cannot definitively say that either the disparities in discipline practices nor the 2007 decision to end busing directly caused the lower academic performance in Pinellas County and the southern county schools specifically, national studies point to the conclusions that these phenomena negatively affect student performance.

Time spent engaged in academic learning and student performance have consistent positive correlations (Greenwood, Horton, & Utley 2002). The National Juvenile Justice Network found in 2015 that black students in Pinellas County had lost a combined 250,000 school days to out-of-school suspension.

In 2010, three researchers (Gregory, Skiba, and Noguera) studied the correlation of racial disparities in achievement and discipline and found that “Suspended students may become less bonded to school, less invested in school rules and course work, and subsequently, less motivated to achieve academic success.”

In 2016, a study concluded that 1/5 of black-white differences in school performance can be attributed to school suspensions (Perry & Morris 2016). Furthermore, the common narrative in support for the use of suspension holds that removing the disruptive students is necessary for the obedient students to succeed. However, exclusionary discipline measures (like out-of-school suspension and arrests) have been shown to hurt not only the disciplined students but even the non-suspended students (Perry & Morris, 2014). In their 2014 study, Perry and Morris discovered that when school’s suspended large numbers of student it has indirect adverse effects on the non-suspended students by creating a punitive environment within the school.

Seeing that Pinellas tops the list of districts in Florida for its use of suspension, the academic failure of its schools (and specifically its black students) should not come as any surprise. Indeed, while these phenomena hold true regardless of race, Pinellas’ disproportionate use of exclusionary discipline measures on black students undoubtedly contributes to the double-digit achievement gap.

Likewise, studies have shown that integrated schools can narrow the black-white achievement gap (Rothstein 2014). And like discipline reforms, focusing on integration benefits not only low-income, minority students like those in southern Pinellas County, but all students. In their report on the benefits of diversity in K-12 schools, Amy Stuart Wells, Lauren Fox, and Diana Cordova-Cobo find the following:

Researchers have documented that students’ exposure to other student who are different from themselves and the novel ideas and challenges that such exposure brings leads to improved cognitive skills, including critical thinking and problem solving.”

Recommendations

Pinellas County failed its black students in 2007 by voting to end integrative busing. But it continues to fail them every day by keeping policies in place that disproportionately hurt black students.

In order to move toward a more equitable system, Pinellas must abandon its use of exclusionary discipline practices. By implementing more specific guidelines for administrators to use before punishing a student, schools can work to bring down the number of suspensions, thereby creating a more positive school environment for all. Additionally, anti-bias training for teachers ought to be implemented as a way to decrease the disparity between black and white disciplinary actions (National Juvenile Justice Network 2015).

School Resource Officers should be likewise trained in anti-bias protocol and additionally in de-escalation techniques. When students are taken out of school for non-violent offenses, no one wins.

To address the stark achievement gap between black and white students and north and south county schools, there exists a few options.

- The county could reinstitute busing

This seems like an unpopular solution based on the public support for the end of busing and without a plan in place to avoid settin racial quotas, the county could inadvertently place itself in violation of the Parents Involved Supreme Court Decision.

- Students could be sorted by economic diversity

Studies have shown that creating economic diversity in schools allows student to receive some of the same benefits that going to a racially diverse school would give them (Schwartz 2009). Additionally, this method of integration is compliant with the Parents Involved ruling.

- Rework the allocation method for county funds

This could work to give south county schools the resources they need in the absence of wealthy community members. Metrics would need to take into account the wealth of the surrounding community. This policy would be difficult to implement within a county because taxpayers who are able move to more expensive neighborhoods to go to higher-achieving schools.

- An expansion of the county’s magnet and fundamental school programs

While this method has done a successful job in the past of creating more integrated schools, it raises the concern that although demographically the schools are desegregated, the school community is not as students exist in racially homogenous pockets.

Conclusion

Until the school board and community leaders can agree on a plan that institutes some combination of these proposals in Pinellas County Schools, the hyper-segregation that has plagued the district will continue to grow alongside the black-white achievement gap. It is no coincidence that these schools became failure factories once the county turned a blind eye to the importance of racial integration. If separate but equal didn’t work in 1954, it surely isn’t working for black children in 2017 Pinellas County.

References

Adams, Jane Meredith. 2015. “Study: Suspensions harm ‘well- behaved’ kids” EdSource. January 8. Accessed April 30th, 2017.

Bureau of Economic Analysis. 2006. Per Capita Personal Income – Florida Counties, Florida and the U.S

Delbray-Pelot, Elizabeth H.. 2007. “NCLB’s Transfer Policy and Court-Ordered Desegregation.” Educational Policy. Vol 21, Issue 5, pp. 717-746.

Fitzpatrick, Cara, Gartner, Lisa, and LaForgia, Michael. 2015. “Failure Factories,” Tampa Bay Times, August 14.

Florida Department of Education. 2015. Closing the Achievement GAP. Interactive Report.

Florida Department of Education. 2006. School Accountability Reports.

Florida Department of Education. 2007. School Accountability Reports.

Florida Department of Education. 2008. School Accountability Reports.

Florida Department of Education. 2009. School Accountability Reports.

Florida Department of Education. 2010. School Accountability Reports.

Florida Department of Education. 2011. School Accountability Reports.3

Florida Department of Education. 2012. School Accountability Reports.

Florida Department of Education. 2013. School Accountability Reports.

Florida Department of Education. 2014. School Accountability Reports.

Florida Department of Juvenile Justice. 2015. Delinquencies in Schools 2013-2014.

Florida Department of Juvenile Justive. 2014. Racial and Ethnic Disparities Benchmark Report 2012-2013.

Gregory, Anne, Skiba, Russell, & Noguera, Pedro. 2010. “The Achievement Gap and the Discipline Gap: Two Sides of the Same Coin?” Educational Researcher, Vol 39, Issue 1, pp. 59-68.

Janssen, J. (2001). An analysis of the legal and historical context of the Pinellas County School District’s separation from court-ordered desegregation established in Bradley v. Board of Public Instruction. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of South Florida.

Morris, Edward W., and Perry, Brea L. 2016. “The Punishment Gap: School Suspension and Racial Disparities in Achievement.” Social Problems. Vol 3, Issue 1, pp. 68-86.

National Juvenile Justice Network. 2015. Pinellas County Schools Report Card.

Perry, Brea L., and Morris, Edward W. 2014. “Suspending Progress: Collateral Consequences of Exclusionary Punishment in Public Schools.” American Sociological Review. Vol 79, Issue 6, pp. 1067-1087.

Pinellas County Schools. 2017. Facts-at-a-Glance. Accessed May 3, 2017. https://www.pcsb.org/Page/650

Pinellas County Schools Office of Assessment, Accountability and Research. 2015. Discipline Disparity.

Rothstein, Richard. 2014. “The Racial Achievement Gap, Segregated Schools, and Segregated Neighborhoods – A Constitutional Insult.” Economic Policy Institute. Vol 6 Issue 4

Schwartz, Heather. 2009. “Do poor children benefit academically from economic integration in schools and neighborhoods? evidence from an affluent suburb’s affordable housing lotteries” PhD dissertation, Department of Philosophy, Columbia University, New York City.

Wells, Amy Stuart, Fox, Lauren, and Gordova-Cobo, Diana. 2016. “How Racially Diverse Schools and Classrooms can Benefit All Students.” The Century Foundation.