Executive Summary

Underrepresented minority, low-income, and first-generation high school students face unique challenges when applying for college and financial aid. With a current average caseload of nearly 500 students, however, school counselors are unable to provide them with the necessary support. In order to help school counselors guide more students through the complex journey to college, the National College Advising Corps (CAC) places recent college graduates–most of whom come from disadvantaged backgrounds themselves–in public high schools across the country. CAC not only addresses the class and racial disparities in college access, but also builds a pipeline of future leaders in school counseling and higher education administration. CAC’S meticulous program design and thoughtful branding make it an instructive model for other college access programs and advocates.

Introduction

At the beginning of each school year ask almost any high school senior what causes them the most stress, and more often than not the response will be “applying to college.” With increasingly competitive admissions rates and seemingly boundless sticker prices on higher education, the college application cycle has come to instill fear in high school students and their families. After all, the stakes are high. Economists and policymakers consistently cite a college degree as the key to better employment prospects and higher wages. For instance, a Pew Research Center study recently found that college-educated millennials earn $17,500 more on average than their peers with only a high school diploma (“The Rising Cost of Not Going to College,” 2014). The economic premium of a college education is even greater for low-income students. According to a report by the Brookings Institution, without a college degree children born in the bottom fifth of the income distribution have a 5% chance of reaching the top fifth of the income ladder as adults. With a college degree, their chance of significant upward mobility more than triples to 19% (Isaacs, Sawhill, & Haskins, 2008).

The drive for more students to obtain a college degree, however, overlooks the immense difficulty of getting to college in the first place. There are several moving parts of the application process that are difficult for students to juggle all by themselves. From writing personal statements, securing letters of recommendation and identifying colleges with the proper fit, to applying for financial aid, student loans and scholarships, preparing for and applying to college are daunting to say the least.

Applying to college is especially daunting for minority, low-income, and first-generation students, who may not have the resources or support outside of school to navigate the complex application process. They often must rely on in-school supports such as their school guidance counselors. But with the average student-to-school-counselor ratio in our nation’s public schools fast approaching 500-to-1, counselors are stretched too thin to provide the necessary college advising to students struggling to map out their postsecondary plans. Additionally, school counselors consistently report that they receive inadequate training in college and career admissions and college affordability (National Office of School Counselor Advocacy, 2012). The sobering result is the underenrollment of qualified students from underrepresented backgrounds in four-year colleges and universities. Currently only 45% of students in the bottom income quartile enroll in postsecondary education, compared with 81% of students in the top quartile (Cahalan & Perna, 2015).

Several programs have started to address this college access gap by offering robust mentoring services and scholarships to high-achieving low-income, minority, and first-generation students. Prominent examples include QuestBridge, Matriculate, the Gates Millennium Scholarship and the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation. These programs represent noble efforts to ensure that the most promising students receive a college education, but their “cream-skimming” practices largely disregard the majority of academically weaker but equally disadvantaged students. In light of the severe school counselor shortage, many of these students resort to facing the college application process alone.

This report is a case study of a national nonprofit aiming to help those who have been left behind. Founded in 2005, the National College Advising Corps (CAC) sends recent college graduates, many of whom are minority, low-income or first-generation themselves, into public high schools across the country to provide school counselors with additional college counseling support. CAC serves a dual purpose of 1) fostering a college-going culture among all students, regardless of circumstance, and 2) giving its college advisers the experience to become future leaders in school counseling and higher education administration. This report will first situate CAC within the current landscape of school counseling in America’s public high schools. It will then analyze the program’s impact, distinctive features, limitations and potential for expansion in order to highlight CAC’s instructive value to other college access programs and advocates.

Knowledge is Power: The role of college counseling in closing the information gap

A critical determinant of whether students apply to and enroll in college is adequate information about the application process. Students from wealthy families usually face few barriers to obtaining such information. Not only do they frequently attend schools with strong college-going cultures and support networks, but they also have the means to afford private counselors to supplement their in-school counseling services (Avery, Howell, & Page, 2014). High-income students with friends and family members who attended college themselves are thus at a significant advantage in the college application process.

Underrepresented student populations tend to be less well-informed for a variety of reasons. Both low-income and first-generation students face the additional challenge of applying for financial aid and understanding which colleges offer sufficiently generous packages (Kuh et al., 2006). They are also more likely to attend schools and live in neighborhoods where the college-going culture and recruitment efforts are not as strong (Hoxby & Avery, 2012). In addition, first-generation students do not have parents who attended college to guide them through the process. Instead they rely on easily accessible information such as online rankings since traveling to visit college campuses for information sessions and interviews is cost-prohibitive (McDonough et al. 1998). Unfortunately these sources of information are extremely blunt instruments that cause students to misperceive the academic, socioemotional, and financial fit of a college. Educators may also be less supportive of underrepresented students throughout the college admissions process due to their race, as research shows that teachers systematically expect lower academic achievement from students of color (Gershenson, Holt, & Papageorge, 2016).

School counselors are uniquely positioned to ensure that students, particularly those belonging to underrepresented groups, are fully informed about college admissions and affordability. One study shows that visiting a school counselor significantly predicts increased college application rates for high school students. Furthermore, according to a study based on data from the National Center for Education Statistics’ Schools and Staffing Survey, an additional high school counselor is associated with a 10% increase in 4-year college enrollment (Hurwitz & Howell, 2014).

Overextended and underutilized: Why school counselors are falling short

Counselors are enthusiastic about promoting college-and-career-readiness within their schools. Nearly three-quarters of school counselors believe they should prioritize giving students an “early understanding of application and admissions processes” (Bridgeland & Bruce, 2011). Even though school counselors can and want to play an important role in closing the information gap and improving college access for disadvantaged students, however, many fail to do so.

The first and foremost reason why is that school counselors, on average, face caseloads of over 450 students per counselor. The American School Counselor Association (ASCA) recommends a student-to-school-counselor ratio of no more than 250-to-1 (“The Role of the School Counselor). This presents an enormous challenge for counselors to develop meaningful one-on-one relationships with students and help guide each student through the college admissions process. Even though school districts would like to expand their counseling staffs, financial constraints prevent administrations from remedying counselor shortages (Karp, 2017).

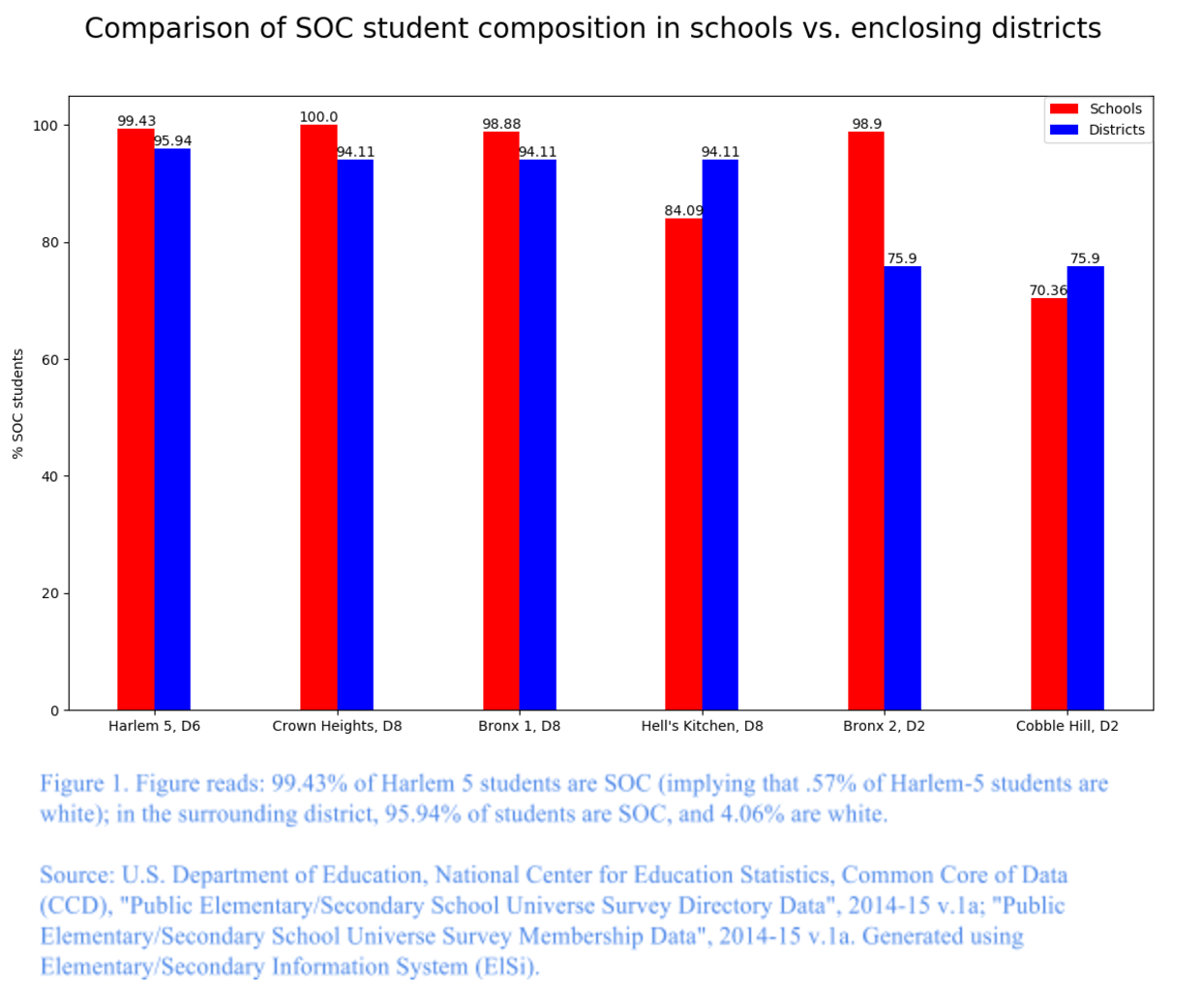

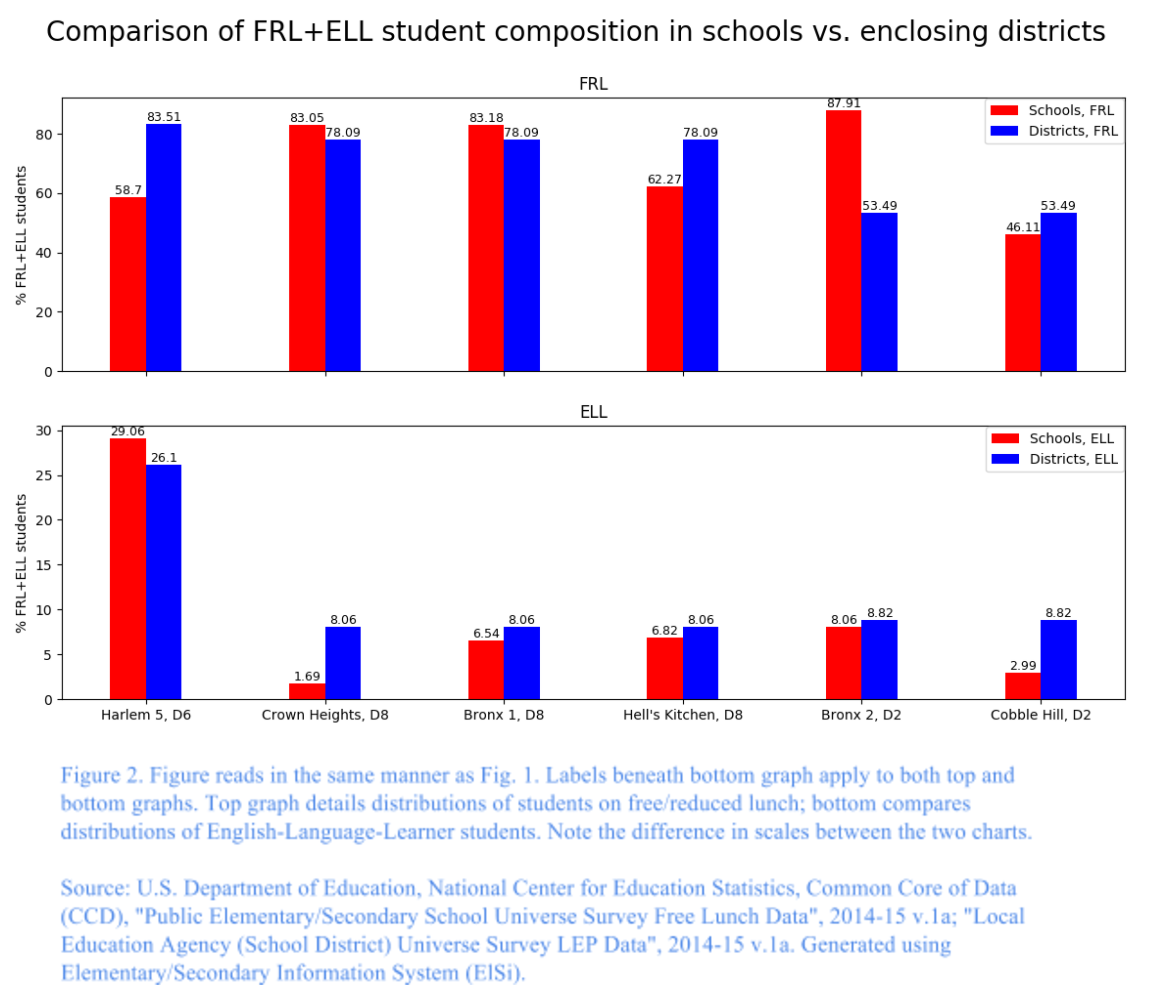

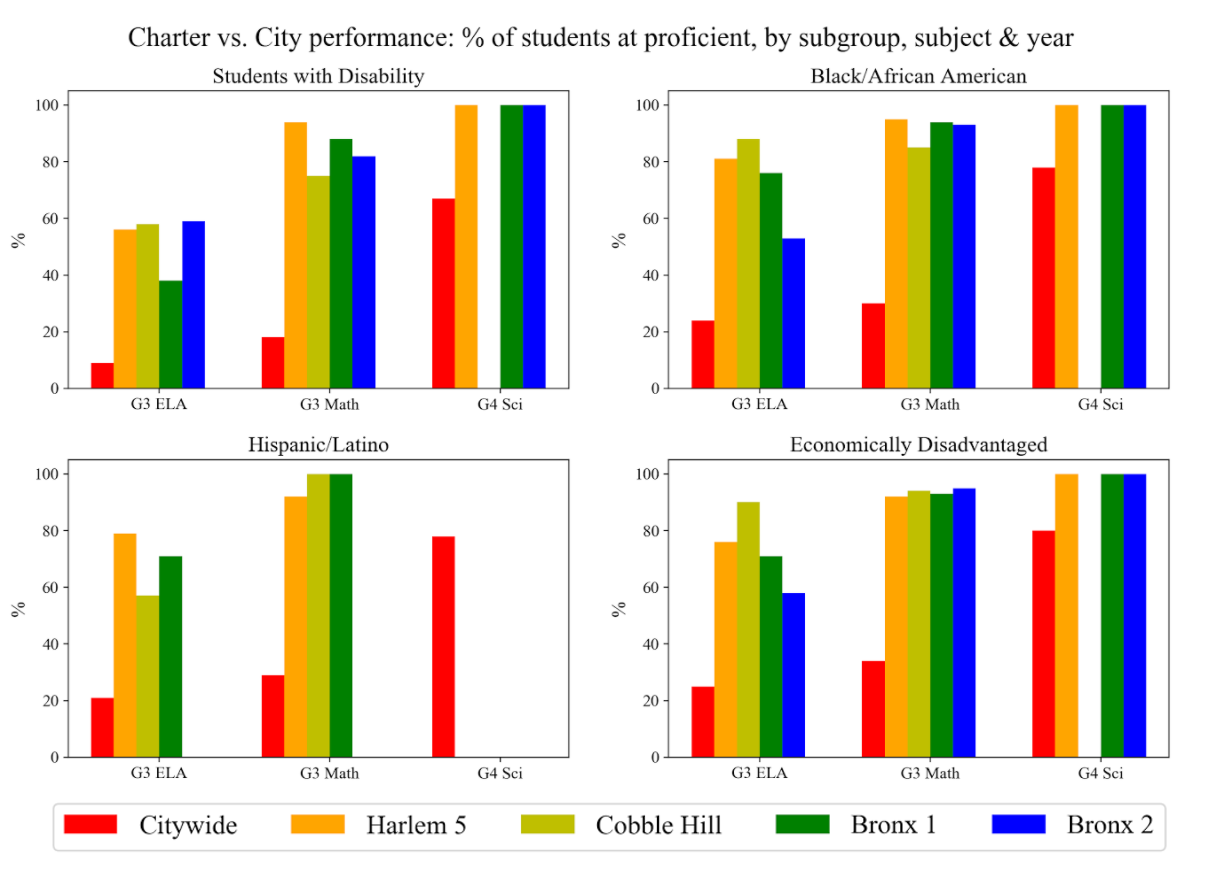

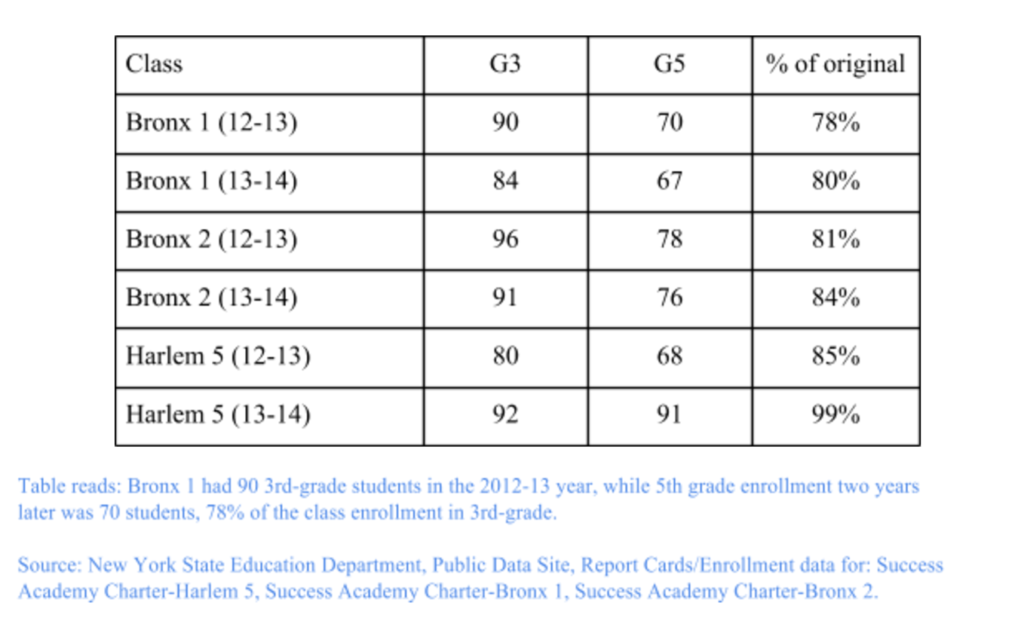

It is also striking to note how students of color and low-income students bear the greatest costs of counseling understaffing:

School counselors are also unable to provide the proper support for students applying to college because their school administrators require them to perform extraneous tasks unrelated to college counseling, such as creating the master class schedule and administering standardized tests. On average, counselors at public high schools devote less than a quarter of their time to “postsecondary admission counseling” (“School Counselors: Literature and Landscape Review,” 2011). In a recent survey of high school counselors, 58% expressed the desire for more time dedicated to “helping students navigate the college application and financial aid processes” (The College Board 2012 National Survey of School Counselors and Administrators, 2012).

School counselors are often the primary college advising resource for underrepresented students and have the potential to play a crucial role in improving their postsecondary outcomes. Currently, however, they are stretched too thin and over-burdened with other responsibilities. Given that understaffing of school counselors is largely a funding problem, how do we increase access to college counseling services for underrepresented students in the short-run?

Killing Two Birds with One Stone: The National College Advising Corps

Founded in 2005 by CEO Dr. Nicole Hurd, the National College Advising Corps (CAC) is a unique college access initiative that provides widespread access to college counseling services for minority, low-income, and first-generation students. CAC places recent college graduates from 24 partner universities into public high schools across the country. These college graduates are tasked with fostering a college-going culture within their school communities and acting as advisers to students navigating the complex process of college admissions, financial aid, and matriculation (College Advising Corps). CAC advisers must attend an intensive four- to six-week summer training program before they begin working, where they learn from experts about the nuances of the college application process, such as SAT/ACT fee waivers and FAFSA. Advisers commit a maximum of two years to serving in their assigned schools. There are currently over 500 advisers serving high school students in 15 different states (March 2016 Member Spotlight: College Advising Corps, 2016).

Since its conception, CAC has served over 600,000 students in both rural and urban high schools. An independent study conducted by researchers at Stanford University analyzed the effectiveness of CAC advisers in Texas and found positive results across several performance indicators (Bettinger et al., 2010):

CAC has also recently added a supplemental program to their in-school college counseling model called College Point eAdvising, which mimics other virtual advising models by providing remote support to high-achieving, low-income students. While the Stanford report only verified the benefits of CAC advisers on the ground, this eAdvising feature clearly allows CAC to cast an even wider net and guide more students through the college application and financial aid process.

Furthermore, Dr. Nicole Hurd envisions CAC as “a double bottom line program” that creates a new generation of education leaders (Hurd, 2016). Key higher education policy debates surrounding financial aid reform, student debt management and loan forgiveness, and the academic and social experiences of first-generation and undocumented students in college have much to gain from school and college counselors who have worked with students on the ground. CAC is thus able to kill two birds with one stone: 1) helping underrepresented students gain access to postsecondary education opportunities, and 2) creating a pipeline of school counselors and leaders into education.

Recipe for Success: What sets CAC apart from the crowd

In addition to achieving impressive results and encouraging more college graduates to consider a career in education, CAC has several features in its design that distinguish it from other college access programs.

First of all, CAC is non-selective with regards to academic achievement. In other words, it does not only provide college counseling services to high-achieving underrepresented students. While programs that do so presumably narrow their focus in order to concentrate its efforts on a smaller demographic, CAC recognizes the value of every student regardless of circumstance and realizes that there are equally valuable alternatives to prestigious four-year universities, such as community college and professional training programs. The fact that CAC has managed to maintain high-quality college advising services at such a large scale is arguably its greatest asset.

CAC’s near-peer mentoring model also gives it a distinct advantage over solely virtual advising platforms. Living within their school communities allows advisers to establish more trust and sustained relations with not only their students, but also their students’ families. In fact, in New York and Detroit, CAC has begun piloting initiatives focused on increasing parent engagement in their child’s journey to college. The power of near-peer mentoring is greatly enhanced by CAC’s prioritization of a diverse advising corps. Over two-thirds of CAC advisers were either low-income or first-generation themselves when they applied to college (Hurd, 2016). It is especially important for college counselors to share a similar background with their advisees because it allows advisers to understand which postsecondary opportunities will best allow their students to thrive academically, socially, culturally, and financially.

Lastly, CAC incorporates details in its design that sometimes go ignored by other college access programs. For instance, whereas education policy is largely biased toward urban schools, advisers serve in both urban and rural settings. CAC also includes college persistence among its performance indicators, which refers to the proportion of students who continue their college education beyond the first year. College persistence is often overlooked but is becoming an increasingly important statistic because policymakers realized that focusing only on matriculation was insufficient if students later dropped out of school. The Stanford evaluation of CAC concluded that 74% of students who met with a CAC adviser and enrolled in college persisted through to their second year (College Advising Corps).

Counseling for America? Potential shortcomings of CAC

CAC is one of several initiatives that replicates Teach for America (TFA), the nonprofit organization founded in 1989 by Wendy Kopp that places recent college graduates in schools for two years. TFA has come under fire for diverging from its original mission of addressing the nationwide teacher shortage and instead sending corps members to schools with adequate staffing, thereby causing competition with and even displacing veteran district teachers (Brewer, 2016). Critics of TFA also point to the detrimental effects of teacher turnover and insufficient training at the expense of student outcomes (Blanchard, 2013). Furthermore, more experienced educators and policymakers lament the proliferation of alternative certification pathways like TFA because they believe they de-professionalize teaching even further (Milner, 2013).

While CAC mirrors TFA’s two-year placement model, it differentiates itself from TFA in two important ways. In terms of program design, CAC is the formal employer of its advisers, meaning its partnering school districts do not need to allocate funds for an additional staff member. Moreover, CAC does not brand itself as a corps of lone saviors. CAC emphasizes that advisers supplement, rather than supplant, existing high school counseling staff, thus helping the school assist more students (“March 2016 Member Spotlight: College Advising Corps,” 2016).

That said, CAC must be careful about contributing to the de-professionalization of school counseling and make greater efforts to explicitly recognize the opportunity costs of forgoing traditional certification. If advisers aim to become a career counselor, CAC needs to acknowledge that earning an accredited degree is necessary for counselors to understand their students’ holistic development and to craft more personalized and beneficial postsecondary education plans.

Conclusion

CAC has several opportunities to expand the scope of its impact in the short term. The organization should continue partnering with more colleges and universities to incentivize a larger pool of college graduates to pay it forward to high school seniors. CAC might also consider broadening its advising services to middle school students, as problems such as low academic performance and financial need arise much earlier than high school. CAC should also extend its performance indicators to include student debt and college persistence rates beyond the second year, which are necessary to understand students’ longer-term postsecondary success. In all, though, over the past decade CAC has made strides toward the goal of helping more underrepresented high school students across the nation apply to and enroll in college.

The college access divide is a multifaceted issue that will require more than one solution in order to fix. CAC represents one such solution that allows more disadvantaged students to reap the lifelong economic and personal benefits of attending college. Looking ahead, however, independent non-profit organizations such as CAC cannot close the college access gap by themselves. College access advocates need to develop long-term structural solutions to these disparities such as equitable school finance laws and more generous financial aid policies.

It is also imperative that educators, postsecondary institutions, and policymakers look beyond college completion as the ultimate goal. College completion is a worthy goal to strive for, but we as a nation must realize that underrepresented minority, low-income, and first-generation students face several barriers to entry. Fortunately, although getting to college is half the battle, each year more and more students can count on the College Advising Corps for support every step of the way.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Professor Mira Debs and Clare Kambhu for their mentorship this semester, and to Elijah Mas, Sara Harris, and Emily Patton for their insightful edits.

Works Cited

Avery, Christopher, Howell, Jessica S., Page, Lindsay. (2014). A Review of the Role of College Counseling, Coaching, and Mentoring on Students’ Postsecondary Outcomes. College Board. Retrieved 3 May 2017 from https://research.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/publications/2015/1/college-board-research-brief-role-college-counseling-coaching-mentoring-postsecondary-outcomes.pdf

Bettinger, E. P., Antonio, A. L., Evans, B., Foster, J., Holzman, B., Santikian, H., & Horng, E. (2010, August). National College Advising Corps: 2010-2011 Evaluation Report (Rep.). Retrieved 3 May 2017 from http://www.socialimpactexchange.org/sites/www.socialimpactexchange.org/files/Evaluation%20Report%2010-11%20(04%2025%2012)%20FINAL.pdf

Blanchard, Olivia. (2013). I Quit Teach for America. The Atlantic. Retrieved 3 May 2017 from https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2013/09/i-quit-teach-for-america/279724/

Brewer, Jameson T. (2016). Teach for America: Lies, Damned Lies, and Special Contracts. Huffpost. Retrieved 3 May 2017 from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/t-jameson-brewer/teach-for-america-lies-da_b_9195600.html

Bridgeland, J., & Bruce, M. (2011, November). 2011 National Survey of School Counselors: Counseling at a Crossroads (Rep.). Retrieved 3 May 2017 from http://media.collegeboard.com/digitalServices/pdf/nosca/11b_4230_NarReport_BOOKLET_WEB_111104.pdf

Bryan, J., Moore-Thomas, C., Day-Vines, N., & Holcomb-McCoy, C. (2011). School counselors as social capital: The effects of high school college counseling on college application rates. Journal of Counseling and Development, 89, 190-199. Retrieved 3 May 2017 from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2011.tb00077.x/epdf

Cahalan, Margaret & Perna, Laura. (2015). Indicators of Higher Education Equity in the United States: 45 Trend Year Report. Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education. Retrieved 3 May 2017 from http://www.pellinstitute.org/downloads/publications-Indicators_of_Higher_Education_Equity_in_the_US_45_Year_Trend_Report.pdf

Hoxby, Caroline M. & Avery, Christopher. (2012). The Missing “One-Offs”: The Hidden Supply of High-Achieving, Low Income Students. National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved 3 May 2017 from http://www.nber.org/papers/w18586.pdf

Hurd, N. F. (2016, May 31). “I Believe in You”: the Power of Near-Peer Advisers and the College Advising Corps. Retrieved 3 May 2017 from http://www.kauffman.org/blogs/edinsight/2016/5/i-believe-in-you-the-power-of-near-peer-advisers-and-the-college-advising-corps

Hurwitz, M., & Howell, J. (2014). Estimating Causal Impacts of School Counselors With Regression Discontinuity Designs. Journal of Counseling & Development, 92(3), 316-327. Retrieved 3 May 2017 from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00159.x/epdf

Identifying and using secondary datasets to answer policy questions related to school-based counseling: A step-by-step guide. (2017). Springer. Retrieved 3 May 2017 from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315698886_Identifying_and_using_secondary_datasets_to_answer_policy_questions_related_to_school-based_counseling_A_step-by-step_guide

Isaacs, Julia B., Sawhill, Isabel W., & Haskins, Ron. (2008, February 20). Getting Ahead or Losing Ground: Economic Mobility in America. Retrieved 3 May, 2017 from https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/02_economic_mobility_sawhill.pdf

Karp, S. (2017, April 26). Few College Counselors At CPS Add Uncertainty To Post-Grad Push. Retrieved 3 May 2017 from https://www.wbez.org/shows/wbez-news/few-college-counselors-at-cps-add-uncertainty-to-postgrad-push/3272c76d-2f03-477a-9a60-400a18866da7

Kuh, G.D., Kinzie, J., Buckley, J.A., Bridges, B.K. & Hayek, J.C. (2006) What Matters to Student Success: A Review of the Literature. Commissioned report for the National Symposium on Postsecondary Student Success: Spearheading a Dialog on Student Success. Washington, DC : National Postsecondary Education Cooperative. Retrieved 3 May 2017 from https://nces.ed.gov/npec/pdf/kuh_team_report.pdf

March 2016 Member Spotlight: College Advising Corps. (2016, March). Retrieved 3 May 2017 from http://www.educational-access.org/our-members/member-spotlight/college-advising-corps/

McDonough, P.M., Lising, A., Walpole, A.M. et al. (1998). Research in Higher Education. Springer. Retriever 3 May 2017 from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40196306

Michael Greenstone et al, Thirteen Economic Facts about Social Mobility and the Role of Education, The Hamilton Project (2013) The Pell Institute, Indicators of Higher Education Equity in the United States: 45 Year Trend Report (2015). Retrieved 3 May 2017 from http://pellinstitute.org/downloads/publications-indicators_of_higher_education_equity_in_the_us_45_year_trend_ Report.pdf

Milner, Rich. (2013). Policy Reforms and De-professionalization of Teaching. National Education Policy Center. Retrieved 3 May 2017 from http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/policy-reforms-deprofessionalization

National Office of School Counselor Advocacy. (2012). The College Board 2012 National Survey of School Counselors and Administrators Report on Survey Findings: Barriers and Supports to School Counselor Success. College Board Advocacy & Policy Center. Retrieved 3 May 2017 from https://secure-media.collegeboard.org/digitalServices/pdf/nosca/Barriers-Supports_TechReport_Final.pdf

School Counselors: Literature and Landscape Review (Rep.). (2011, November). Retrieved 3 May 2017 from http://media.collegeboard.com/digitalServices/pdf/advocacy/nosca/counselors-literature-landscape-review.pdf

Seth Gershenson, Stephen B. Holt, & Nicholas W. Papageorge. (2016). Who believes in me? The effect of student–teacher demographic match on teacher expectations. Economics of Education Review, Volume 52. Retrieved 3 May 2017 from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2016.03.002

The College Board 2012 National Survey of School Counselors and Administrators (Rep.). (2012, October). Retrieved 3 May 2017 from https://secure-media.collegeboard.org/digitalServices/pdf/nosca/Barriers-Supports_TechReport_Final.pdf

The Rising Cost of Not Going to College. (2014, February 11). Retrieved May 03, 2017, from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2014/02/11/the-rising-cost-of-not-going-to-college/#

The Role of the School Counselor (Rep.). (n.d.). Retrieved 3 May 2017, from https://www.schoolcounselor.org/asca/media/asca/home/RoleStatement.pdf