Akintunde Ahmad

African American Male Achievement

Welcome to Oakland, California, the most diverse city in the United States. In Oakland, you can find it all. Every ethnicity, every language, every religion. From artists and athletes and academics, to bikers and dancers and teachers, this city truly captures the beauty that encompasses all forms of humanity. Oakland is a special place. On one hand the success of the city’s sports teams, growth in job markets, and unique culture are to be praised and celebrated. On the other hand, the city’s criminal justice system and socio-economic education inequalities are in desperate need of fixing. While some demographic groups can live in Oakland and reap all of the benefits that this amazing city has offer, other marginalized groups are being forgotten and left to deal with the burden of being on the receiving end of the city’s economic and social inequality. To be blunt, the African-American community in Oakland is in need of healing. Specifically, African-American males are consistently getting the short end of the stick when it comes down to what cities like Oakland have to offer. Black males are the lowest achieving pupils in our nation’s schools, the most likely to be arrested and incarcerated, and the most likely to fall victim to gun violence. These issues are intersectional, with education, incarceration, and economic inequality being the main issues that need fixing. These problems have persisted throughout history, and while there has been much talk about the problems, there haven’t been many effective solutions. However, the Manhood Development Program in Oakland, CA is taking on the challenge to change the narrative for black men by infiltrating Oakland Unified School District’s classrooms and implementing strategies and programming that target the city’s most troubled demographic group.

Why African-American Males?

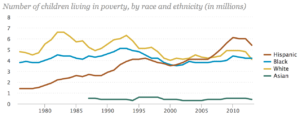

So why exactly do cities need programs targeting and assisting African-American males? Lets look at the statistics. A Pew Research study tells us that across the United States, “black children were almost four times as likely as white or Asian children to be living in poverty in 2013, and significantly more likely than Hispanic children” (Patten and Krogstad, 2015).

Graphic Taken From Pew Research Study, 2015

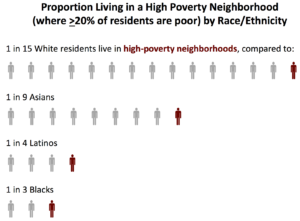

A report by the Schott Foundation for Public Education states that in the 2012-13 school year, the national graduation rate was 59% for Black males, 65% for Latino males, and 80% for White males (Schott Foundation, 2015). According to a report done by the Sentencing Project, if current trends continue, one of every three black American males born today can expect to go to prison in his lifetime (Sentencing Project, 2013). Now, lets shift the focus to Oakland specifically. When it comes to incarceration, a 2013 report stated that 73.5 percent of juvenile arrests in Oakland are black males, even though they make up only 29.3% of the Oakland Youth population (Black Organizing Project, 2013). When it comes to education, black males have consistently had the lowest graduation rates in Oakland’s public school district. In 2011-2012, African-American males graduation rate was 52.4%, compared to a district graduation rate of 66.8% (Oakland Unified School District, 2014). When observing overall inequality, a report by the Alameda County Public Health Department stated that compared to a white child born in the Oakland Hills, a black child born in West Oakland is 13 times as likely to be poor and a four times less likely to be reading at grade level in the fourth grade (Brown, 2016).

Graphic Taken From The Community Assessment, Planning, Education, and Evaluation Unit of the Alameda County Public Health Department, 2015.

Introducing the African-American Male Achievement Program

The evidence is clear. In cities like Oakland, African-American boys need help, and in more ways than one. In order to effectively change the narrative for African-American males, programs must attempt to combat not only issues that exist on school campuses and in the classroom, but also account for the economic inequality, mass incarceration, and disparate rates of violence that effect young black men. Thankfully, in Oakland, CA, the Office of African-American Male Achievement is doing something to change that. By bringing in African-American male teachers to the classroom, teaching curriculum focused on African-American history, and building personal mentorship relationships, the Manhood Development Program has been a model for other urban districts to look to to successfully uplift its black males with the hopes of having them graduate college ready. In 2010 the Oakland Unified School District created the Office of African-American Male Achievement, spearheaded by Chris Chatmon, with the vision of stopping “the epidemic failure of African-American male students in the Oakland Unified School District (OUSD)”, and the mission of creating “the systems, structures, and spaces that guarantee success for all African-American male students in OUSD” (OUSD, 2017). The Oakland Unified School District is the first school district in the United States to create a department dedicated to addressing the specific needs of African-American male students. While there had many initiatives in the past that tried to combat the issues that African-American males in the district faced, Oakland’s Board of Education, Urban Strategies Council, and the East Bay Community Foundation came to the conclusion that in reality, these past efforts had done little to nothing to actually impact the experience of the district’s black males (OUSD, 2017).

Following the inception of the Office of African-American Male Achievement, or AAMA, the Manhood Development Program (MDP) was then initiated in 2010. This was the flagship program of the newly created department, aimed at implementing the change they wanted to see on the ground level. The program functioned as such: African-American male instructors were handpicked based on their cultural competency and ability to relate to youth, in addition to their past teaching experiences. Each instructor taught an elective course that was offered five days a week during the school day. Class sizes ranged from 20-25 students, with classes mixed up based on student achievement level. One third of the class was high achieving, one third was average, and the other third was under-achieving. The program was originally instilled in only three schools in OUSD, but currently functions in twenty-four schools throughout the district, existing in elementary, middle, and high schools (Wisely, 2016).

The Manhood Development Program revolved around three central goals:

1) Decrease suspensions and increase attendance. 2) Decrease incarceration and increase graduation rates. 3) Decrease the opportunity/achievement gap and increase literacy. One of the first steps at achieving these goals is getting a commitment from the students to standards of the Office of African-American Male Achievement (Watson, 2014).

The Standards of Brotherhood

- Respect for ourselves and each other.

- Keep it 100 (Tell the truth)

- Lift Ups, No Put Downs

- Look out for each other

- Play Hard, but Also Work Hard

- Represent Your Best Self At All Times

- Be On Time

- Be responsible for your own actions

- Build the Brotherhood

- Trust yourself and others in the brotherhood

With these agreements made, the instructors then work on building a family environment in the classroom and across all students in the district. Students refer to one another as “Brother ____” or “king”, terms that reinforce the value that each individual has, and the familial community the program wishes to instill amongst its members. A district leadership council exists amongst the students with representatives from each school, making sure that program ideals and values line up across the different schools. Students attend leadership conferences together, and travel as far as New York City to learn about what it means to be a black man (Brown, 2016). Students also participate in the annual African-American Male Achievement Symposium, where each school’s class showcases what they have learned about black manhood at Oakland’s historic Fox Theater. And the instructor’s serve as much more than just teachers. They act as mentors and vouch for their students, often serving as the intermediaries between their students and the other teachers in the school when issues arise.

In the classroom, the curriculum is structured around studying black history, building self-esteem, and learning professionalism. It’s much more than just academics. Students are also learning life readiness skills. Younger students learn about the narratives and images of historically significant black people. The high school students go even deeper, covering everything from ancient African civilizations to the Civil Rights movement to current issues like Black Lives Matter. But it doesn’t stop here. Students learn skills like how to tie a necktie, dress professionally, or how to present themselves in public. They talk about the struggles that they face on a day-to-day basis as black men, with issues ranging from gun violence in their communities to how to deal with police brutality (Lee, 14). These are issues that most black male students are not often afforded the opportunity to openly discuss, rather it be amongst peers or structured in a classroom. By having an older black male that has experienced similar situations, Manhood Development Program teachers are able to facilitate dialogue that stimulates emotional and mental growth out of black male students that other instructors just would not be able to achieve.

The Change

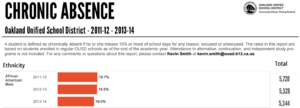

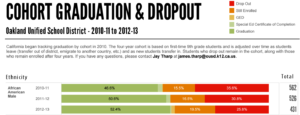

Now, lets examine some of the statistics of the district since the founding of AAMA and the instillation of the Manhood Development Program. The graduation rate for African-American males increased from 51% in 2011-12 to 61% in 2014-15, a major 10% jump. The number of African-American males on the honor roll rose from 20% in 2013-14 to 32% in 2015-16, a 12% increase. The suspension rate fell from 22% in 2010-11 to 10% in 2014-15, a 12% decline. The chronic absence rate fell from 19.7% in the 2011-2012 school year to 18% in 2013-2014. The number of students in the juvenile justice system fell 40%, from 273 in 2010-11 to 164 in 2014-15 (Wisely, 2016).

Graphs obtained from the OUSD District Data Website

Based on these charts, it is easy to see that since the founding of the Office of African American in 2010, the district’s African-American males are making improvements. To give more statistics, grade point averages are now 25 percent higher for Manhood Development Program students than for Black male students who haven’t taken the course. District-wide, the Black male graduation rate has improved from 42 to 57 percent since the course was introduced. The number of Black male high school seniors who qualify for admission to the University of California (UC) or California State University is 6 percent higher among the Manhood Development Program participants than for non-participants (OUSD, 2017).

And while these metrics on academics, behavior, and attendance are important, there is even more data pertaining to how the Manhood Development Programs have affected students attitudes and approach in school. Look at these statistics. 43% of students report that their teachers respect them versus 77% for the MDP participants. 44% of students report that their other teachers want them to get good grades versus 85% for MDP. 65% of students report that their other teachers expect them to succeed versus 92% for MDP (Watson, 2014). Clearly, the instructors in MDP are having an impact on student’s lives that exceeds just their academic performance.

Why Does It Work?

Representation matters. According to a 2017 study by the IZA Institute of Labor Economics, “exposure to a black teacher during elementary school raises long-run educational attainment for black male students, especially among those from low-income households” In addition, estimates suggest that exposure to a black teacher in primary school cuts high school dropout rates by 39%, and also raises college aspirations along with the probability of taking a college entrance exam (IZA, 2017). In a report on reflections from black teachers, the educator’s experiences in the classroom reflect what research has proven. “Teachers of color bring benefits to classrooms beyond content knowledge and pedagogy. As role models, parental figures, and advocates, they can build relations with students of color that help those students feel connected to their schools. And they are more likely to be able to enhance cultural understanding among white colleagues, teachers, and students”. The report went on to say “Black teachers in our sample, much like in other research, felt they had an easier time building connections with students, especially Black students, because of perceived cultural and experiential similarities. They said this immediate, surface-level connection with many Black students helped those students trust them and feel safe in their care” (Griffin and Tackie, 2016). So, just by having a black male teacher that they can relate to on campus, student’s learning experiences are transformed. The feeling that they have somebody that they can trust and turn to with their issues subsequently affects their viewpoints towards their overall learning experience.

In addition to the students being able to see themselves in their teachers, the culturally relevant topics that they study also help with garnering interest in academics. While so many of the schools that have the highest percentages of students of color are teaching to standardized tests, and neglecting relevant social studies, the Manhood Development Program’s curriculum actually engages its students in topics that they can relate to. One Huffington Post article reads “we should be preparing these students for the challenges of race in America with a broader knowledge base and more elective courses. Instead, we are robbing a generation of students of ownership over their identity by turning the social sciences into collections of reading quizzes” (Hartmann, 2017). The intersectional academic skills of black male students in Manhood Development Program are improved by using engaging topics to gauge student interests. The language used in the program also adds so much value. The use of the N-word is prohibited, and as previously stated, students refer to each other as king or brother in order to reinforce the ideal that each student has immense value, and should be respected and treated as such.

The Future of the Program: Oakland and Beyond

While the Manhood Development Program has had a significant impact on district achievement scores for black males, in reality, the amount of black males who are actually enrolled in these programs is but a fraction of the African-American males in the district. An MSNBC article reported that in 2014, the program was only reaching about 400 students a year, roughly 4% of black males in the district (Lee, 2014). In 2016, the program existed in 24 schools and served over 800 students (Wisely, 2016). Each year, the Office of African-American Male Achievement strives to scale up this program to reach more of its young black males by instilling the MDP in more of the district’s schools. The effects of this program have proved to be nothing but positive, however at the end of the day it takes a lot of money for these kinds of programs to function over long periods of time. The program currently has an annual operating budget of $3.5 million, with half funded by the district and the other half funded by private donors (Wisely, 2016). In a district that has recently called for $25.1 million in cuts over the next 18 months, the future of the Manhood Development Program could be in jeopardy (Tsai, 2017). Without increased funding, realistically there is no way for the program to reach more of the black male students in need in Oakland.

The Office of African American Male Achievement has been transparent about its process of coming to existence, and has made its curriculum and operating methods open for other districts to replicate. There are plenty of districts across the United States that could benefit from implementing a Manhood Development Program, and the hope is that other district’s administrators and officials will recognize the impact this program has had in Oakland and bring a program like it to their respective city’s. In 2014, Minneapolis Public Schools launched their own Office of Black Male Student Achievement, which has already showed promise in improving the academic achievement of its students (Wisely, 2016).

What’s Next?

In 2016, Oakland founded its Department of Equity, with the mission of “eliminating the predictability of success and failure that currently correlates with any social or cultural factor, interrupting inequitable practices, examine biases and create inclusive and just conditions for all students, discovering and cultivating the unique gifts, talents and interests that every student possesses, understanding that we must first ensure EQUITY before we can enjoy EQUALITY” (OUSD, 2017). As a result of the foundation of this department, three new programs have been developed to target the city’s other demographic groups in need. There are programs for African American Girls and Young Women Achievement, Latinx and Indigenous Student Achievement, and Asian Pacific Islander Student Achievement. These programs will be launched in the 2017-2018 school year, so there is no data on their effectiveness yet, but the hope is that they can replicate the successes of the Office of African American Male Achievement.

Conclusion

Many cities across the United States have struggled with finding effective methods of combating the inequalities of society. Far too often, African-American males are the demographic group that is impacted most by this inequality. In 2010, the Office of African-American Male Achievement was founded in the Oakland Unified School District. Its flagship program, the Manhood Development Program, implemented an Afro-Centric academic curriculum with self-esteem building techniques taught by African-American male teachers into classrooms throughout the district. Graduation rates increased, alongside grade point averages and attendance rates. School suspensions declined, while attitudes towards Manhood Development teachers were reported to be far more favorable than that of other teachers. The successes of this program are clear, and the hope is that this program is able to expand in the Oakland Unified School District, and be replicated across the United States in urban cities like Oakland.

Works Cited

The Black Organizing Project, Public Counsel, and ACLU of Northern California. “From Report Card to Criminal Record: The Impact of Policing Oakland Youth.” US Human Rights Network. N.p., 08 Jan. 2014. Web. 03 May 2017.

Brown, Patricia Leigh. “Lessons in Manhood for African-American Boys.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 04 Feb. 2016. Web. 03 May 2017.

The Community Assessment, Planning, Education, and Evaluation Unit of the Alameda County Public Health Department. “How Place, Racism, and Poverty Matter for Health in Alameda County – Documents.” The, 25 Feb. 2016. Web. 03 May 2017.

Gershenson, Seth, Cassandra M. D. Hart, Constance A. Lindsay, and Nicholas W. Papageorge. “The Long-Run Impacts of Same-Race Teachers.” IZA. EconPapers. N.p., 21 Mar. 2017. Web. 03 May 2017.

Griffin, Ashley, and Hilary Tackie. “Through Our Eyes: Perspectives and Reflections From Black Teachers.” The Education Trust. N.p., n.d. Web. 03 May 2017.

Hartmann, Jennifer. “Teaching Black History to Our Students of Color.” The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, 03 Feb. 2017. Web. 03 May 2017.

Howard, Tyrone C. “Culturally Responsive Pedagogy.” Encyclopedia of Diversity in Education. 2011. Print.

Klein, Rebecca. “These Schools Made A Commitment To Black Boys And Are Now Seeing Big Results.” The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, 17 Feb. 2015. Web. 03 May 2017.

Lee, Trymaine. “How Oakland’s Public Schools Are Fighting to save Black Boys.” MSNBC. NBCUniversal News Group, 15 July 2014. Web. 03 May 2017.

Oakland Unified School District. “African American Male Achievement.” Oakland Unified School District / About Us. N.p., n.d. Web. 03 May 2017. Retrieved from www.ousd.org/Domain/78

Oakland Unified School District. “African American Male Achievement.” Oakland Unified School District / District Data. N.p., n.d. Web. 03 May 2017. Retrieved from www.ousd.org/Domain/78

Oakland Unified School District. “African American Male Achievement.” Oakland Unified School District / Events. N.p., n.d. Web. 03 May 2017. Retrieved from www.ousd.org/Domain/78

Oakland Unified School District. “African American Male Achievement.” Oakland Unified School District / Frequently Asked Questions. N.p., n.d. Web. 03 May 2017. Retrieved from www.ousd.org/Domain/78

Oakland Unified School District. “African American Male Achievement.” Oakland Unified School District / Programs and Services. N.p., n.d. Web. 03 May 2017. Retrieved from www.ousd.org/Domain/78

Oakland Unified School District. “Office of Equity.” Oakland Unified School District / Home. N.p., n.d. Web. 03 May 2017. Retrieved from www.ousd.org/Page/15687

Oakley, Doug. “State and National School Districts Copying Oakland’s Black Male Achievement Office.” East Bay Times. East Bay Times, 15 Aug. 2016. Web. 03 May 2017.

Patten, Eileen, and Jens Manuel Krogstad. “Black Child Poverty Rate Holds Steady, Even as Other Groups See Declines.” Pew Research Center. N.p., 14 July 2015. Web. 03 May 2017.

The Schott Foundation for Public Education. “Black Lives Matter: The Schott 50 State Report on Public Education and Black Males.” Schott Foundation for Public Education. The Schott Foundation for Public Education, 01 Feb. 2015. Web. 03 May 2017.

Tsai, Joyce. “Oakland: School Superintendent Calls for $25.1 Million in Cuts, Orders Hiring Freeze.” East Bay Times. East Bay Times, 12 Jan. 2017. Web. 03 May 2017.

Watson, V. The Black Sonrise: Oakland Unified School District’s Commitment to Address and Eliminate Institutionalized Racism, an evaluation report prepared for the Office of African American Male Achievement, Oakland Unified School District, Oakland: CA. December 2014.

Whitney, Spencer. “75 Percent of Juvenile Arrests in Oakland Are Black Males, Says Report.” Oakland Local. N.p., 11 Oct. 2013. Web. 03 May 2017.

Wisely, John. “First-in-the Nation School Program Turns Boys into Strong Black Men.” Detroit Free Press. N.p., 27 Nov. 2016. Web. 03 May 2017.