Sara Harris

EDST 245: Public Schools and Public Policy

Professor Mira Debs

May 3rd, 2017

Don’t Say Gay:

Why States Are Erasing LGBTQ Students, and How They Have the Power to Change It

Executive Summary

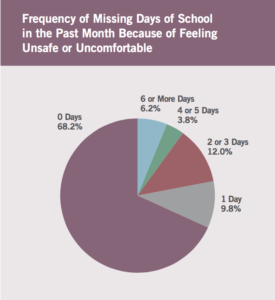

Over the past 60 years in particular, the American public education system has seen significant progress toward creating an inclusive, equitable environment for all students; there has been equal challenges met along the way, however. Inclusive educations has made numerous strives, yet today, some students still remain unsafe and unrepresented. More than half of LGBT-identifying students report feeling unsafe at school, the majority reporting having experienced direct verbal harassment (The 2015 National School Climate Survey). Not only are they facing this bullying, harassment, and discrimination on a personal level, but many still face this treatment on an institutional level.

While some states have active exclusionary laws (known as “no promo homo”), others protect students from harassment or discrimination, and California stands alone in requiring LGBTQ inclusive curriculum. Previous culture and history wars have left the power of forming and enforcing standards to the discretion of the states, in hopes to better cater to more localized needs, but these laws have been upheld at the detriment of LGBTQ students. Maintaining these laws creates a culture of silence in schools which perpetuate a dangerous environment for these students, and leave educators fearing legal backlash upon mention of the topic. This report will provide historical context for the social and cultural barriers to revising curriculum standards, and review the legality of existing “no promo homo” laws. It will also make the case that not only should states remove discriminatory “no promo homo” laws, but adopt standards mandating inclusive curriculum to ensure a quality education.

Introduction: What is No Promo Homo?

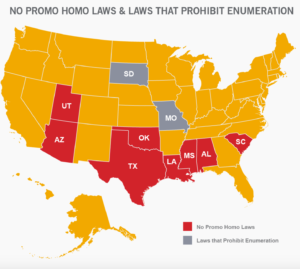

LGBTQ students in American public schools are not afforded any level of guaranteed safety or representation in the classroom. The responsibility to champion inclusive curriculum falls on the state level; today, California remains the only state to have passed such requirements, while seven states– Alabama, Arizona, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Texas, and South Carolina– have policies known as “no promo homo” laws that effectively silence teachers on the topics of LGBTQ issues, history, and health (The Trevor Project, 2017). These laws range in exact language and context, but all have the same effect: erasing these students’ presence and any attempt by educators to acknowledge or support them.

Within the modern education reform debate, attempts to create inclusive, diverse curriculum have taken center stage many times; this has influenced numerous initiatives and decisions even when not the primary focus. In these seven states, educators cannot even entertain the idea of LGBTQ-inclusive curriculum, let alone speak about the topic in the classroom. Alabama currently mandates that “an emphasis, in a factual manner and from a public health perspective, that homosexuality is not a lifestyle acceptable to the general public and that homosexual conduct is a criminal offense under the laws of the state” (Alabama Code Title 16). This references the state’s unenforceable criminalization of homosexuality, a law that was federally overturned in Lawrence v. Texas in 2003. In Arizona, districts are forbidden to include curriculum which “1. Promotes a homosexual life-style or 2. Portrays homosexuality as a positive alternative life-style.” (Arizona Revised Statutes Title 15. Education § 15-716)

These laws perpetuate an image of criminality and shame surrounding students’ identity, and enforce discussion of the topic to be considered taboo. States hold the power to regulate curriculum guidelines and standards, using national standards as a resource to inform and craft the curriculum. The control is given to states in order to allow curriculum formation to happen at the local level to better fit the needs of individual communities (Nash, Crabtree, & Dunn 2000; Zimmerman, 2005). These curricular guidelines come at the cost of students’ wellbeing. States have no legal need to perpetuate a standard of sexual conduct (Lugg, 2003). The idealization of heteronormative relationships is not grounded in any constitutional or other official framework, but rather a reflection of local culture.

All states should be required to remove all language which promotes or mandates discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity in the classroom. Repealing all “no promo homo” laws is the only way towards ensuring safety, inclusion, and quality education for LGBTQ students. This need be accomplished either at the state level, which was accomplished in Utah in 2017, if not enforced by the US Department of Education at a national level. Furthermore, states must move towards adopting LGBTQ inclusive curriculums, as the benefits of inclusive curriculum affect all students.

Background: The History of Modern History Curriculum

In the 1990’s, a social and political battle was ignited by a the development of a new system of national history standards. The “Culture Wars”, a resulting debate over the formation of these standards, were fueled by partisan motives and political ties (Nash et. al., 2000). This debate, however, was not the first of it’s kind in American history. After the Civil War, textbooks in Northern and Southern states reported vastly different accounts of the war and antebellum life. The 1920’s saw a rising critique of history textbooks’ accounts of slavery. In the early 1940’s conservative parent groups, led a movement against allegedly “un American” textbooks, primarily written by Harold Rugg. The Rugg books were criticised for propagating “treasonous”, anti-american ideas; within five years the initiative, spearheaded largely by the American Legion, was successful in encouraging districts to phase out the Ruggs book. The 1950s and 60s saw an influx of more diverse Americans graduated with history degrees. This increase in scholarship coincided with the civil rights movement in the 1960’s, and textbooks started to reflect a shift toward a more accurate, honest portrayal of slavery (Nash et. al., 2000; Zimmerman, 2005).

The 1990’s Culture Wars is the most recent iteration of the same political struggles surrounding curriculum. Fueled by an era of political and social tension, much of the debate surrounding the National History Standards followed partisan lines. The narrative and outcome was little different to it’s predecessors; the conflict was, at its core, between those advocating for a “traditional”, celebratory history of American and “American” values, and those advocating for the addition of new material, and a critical presentation of standard events and figures. (Zimmerman, 2005). The revised standards were not as progressive as the first proposed, providing more of an outline for states and districts to form their own curriculum. It is not the exact result of any specific “history war” in this country’s past that was formative of today’s curriculum standards or mandating processes. It is of greater importance that these moments quickly turned to political, social, and culture wars, through which players fought for which morals, identities, and collective national image would be propagated in schools, through the curricular content which would find itself in new textbooks. In the midst and following the public national debacle surrounding the national standards, in the 1990’s, the main power to create and enforce curriculum fell on the state and local level.

This nation’s historical controversy and disagreement over history has lead to the current climate in which “no promo homo” laws can continue to influence school climate and curriculum. There are no nationally mandated curriculum standards, however the department of education does protect against discrimination “on the basis of race, color, and national origin, sex, disability, and on the basis of age,” (United States Department of Education). This lack of explicit protection in combination with the long-standing controversial and subjective nature of history/social study standards, give states and local districts have the power to either deny these students a positive, inclusive experience.

The Necessity of LGBT-Inclusive Curriculum

California is the only state which features language requiring the explicit inclusion of positive representation of LGBTQ figures and historical contributions. Other than the seven previously mentioned states with “no promo homo” laws, no other states have specific curriculum guidelines in this area, however, this alone is not sufficient. By not passing inclusive standards, these states remain complicit in the adversity faced by LGBTQ students by allowing their history and identities to go unrepresented. The benefits of inclusive curriculum benefit all students, and build a healthy climate for LGBTQ identified students.

The two main subject areas which topics of LGBTQ history and issues arise are in health education and history and social studies (Snapp, Burdge, Licona, Moody, & Russell, 2015). Most of states “no promo homo” laws were passed in the 1980’s and 90’s in response to the AIDS crisis and with the rise of anti-LGBTQ inclusive laws and policy (Lambda Legal, n.d.). These laws, for the most part, are focussed on health and sex education, but their reach does not stop there, often affecting teachers willingness and ability to talk about LGBTQ issues, including harassment or mistreatment within the school (Lambda Legal, n.d.). This creates a culture of silence and shame surrounding the student’s’ identity. Of students who reported incidents, 63.5% said that school staff did not respond or told the student to ignore it. 16.7% were prohibited from discussing or writing on LGBTQ topics for their assignments, while an additional 16.3% were prohibited from doing so in their extracurricular activities (The 2015 National School Climate Survey).

Inclusive curriculum appears most often in history and social studies classrooms (Snapp et. al., 2015). These sections in the curriculum may have positive impacts on students who identify as LGBTQ, but they can easily fall short of their full potential. These lessons are often taught as stand alone topics, and the connections to broader social justice work and can often be missed (Snapp et. al., 2015). Educators can miss valuable teaching moments, even if they are trying their best to incorporate these topics. This speaks to the importance of a structured curriculum reflected in the textbook and teaching materials teachers use. Inclusive curriculum not only teaches all students about specific events and figures important to the LGBTQ community, it also increases the awareness of the obstacles and challenges these students face. Non LGBTQ identifying students may be able to appreciate and acknowledge the difficult position of their peers more, and empathize with them when presented with history and current events in particular. It can also be related to other issues of social justice, and equal rights which students may have learned about beforehand, encouraging them to recognize and relate the injustice and discrimination faced by the LGBTQ community as similar to that faced by other groups (Athanases & Larrabee, 2003).

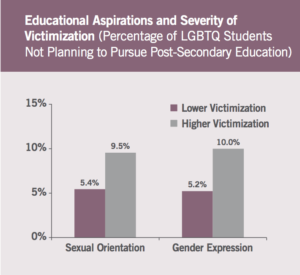

At schools with inclusive curriculum, LGBTQ students are psychologically healthier, and perform better in the classroom (Russell, Fish, 2016). They are more supported, miss less classes, and experience fewer instances of harassment and bullying. Overall, these factors contribute to a safer climate which is fostered by these students’ peers and teachers. The two most effective factors in encouraging students to stop bullying and harassment is witnessing teachers intervene to stop harassment and, most of all, seeing other students do so (Wernick, Kulick, & Inglehart, 2013). By introducing curriculum which demystifies and illuminates LGBTQ history and issues, students will be more likely to actively speak out against negative remarks, and bullying. This creates a positive cycle in which other students would be engaged, improving the overall culture and climate of the school.

The perceived safety of LGBTQ students by their peers has been shown to be an indicator of the heteronormative school culture (Toomey, McGuire, & Russell, 2012). In schools with more inclusive curriculum, students reported a safer environment for their LGBTQ, and specifically gender nonconforming peers. These students perceived safety, may not reflect their reality as many still report high instances of harassment.

Students who attend schools with LGBT inclusive curriculum experience also less verbal and physical harassment and assault. According to GLSEN 2015 School Climate report, 40.4% of students felt unsafe because of their sexual orientation as opposed to 62.6% in schools without inclusive curriculum, 18.6% of students missed school in the past month as opposed to 35.6%. In these environments, LGBTQ students feel more welcomed and accepted by their peers, reporting hearing “gay” used often in a negative way 49.7% opposed to 72.6%, and general homophobic remarks 40.6% opposed to 64.1% of students. They were also more likely to report their classmates were somewhat or very accepting of LGBTQ people, 75.8% compared to 41.6% (The 2015 National School Climate Survey).

Overall, positive representation in the classroom improves the school environment by educating all students, but only 22.4% of LGBTQ students reported being taught positive representation about LGBTQ people, history, or events and 17.9% had been taught negative content (The 2015 National School Climate Survey). Less than half of students reported being able to find information about LGBT-related issues in their school library. This shows that having no requirements is not enough to promote an inclusive environment. The standard cannot be set so low, that the simple absence of discriminatory laws is seen as exemplary.

California: An Agent For Change

In 2012, California became the only state mandating LGBTQ inclusive curriculum standards. The changes to the law were minimal. The bill which introduced these changes did not change any of the state’s standards or curriculum directly. It did, however, ensure that schools and districts make efforts to actively include positive representation of LGBTQ figures. Among other previously underrepresented groups “lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender Americans” were added to the section mandating the “ study of the role and contributions… to the economic, political, and social development of California and the United States of America, with particular emphasis on portraying the role of these groups in contemporary society” (California Department of Education).

The other main change which this bill initiated was new requirements for textbooks and other educational materials. “Education Code Section 60040 directs governing boards to only adopt instructional materials that accurately portray the cultural and racial diversity of our society” (California Department of Education.). Education Code Section 51501 and Section 60044 outline similar prohibitions on instructional materials “reflecting adversely upon persons because of their race, sex, color, creed, handicap, national origin, or ancestry”; this bill added “sexual orientation” to the list (S.B. 48, 2011).

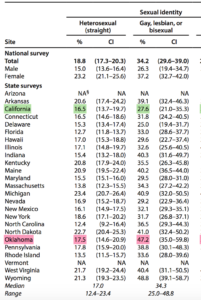

It can be seen in the Center for Disease Control’s report on “Sexual Identity, Sex of Sexual Contacts, and Health-Risk Behaviors Among Students in Grades 9–12” that LGBTQ students in California experience less harassment and bullying at school. In the figure below, the difference in percentage of heterosexual, and gay, lesbian, and bisexual students bullied on school property is much lower in California than Oklahoma, the only state with reported figures which has “no promo homo” laws. Oklahoma has the second highest percentage of LGBTQ students reporting being bullied on school property, and the highest difference between heterosexual and LGBTQ students, at near 30% more.

In California students at several grade levels will learn appropriate topics such as different, diverse types of family structure, landmark cases, and the history of the modern gay rights movement. Perhaps the most widespread effect of this bill will be the new textbooks and instructional materials districts adopted in the 2016-17 school year (California Department of Education). The new standards will be reflected in materials adopted for grades k-12. Surrounding states will have access to these materials as well, and opportunity to adopt them, and mold their own curriculum to the new materials. This has the potential to create a ripple effect of inclusive curriculum in schools and districts; the majority of the work has been done, these materials need only be adopted, and these topics integrated into classrooms.

Considering Implementation

Implementation of LGBTQ inclusive curriculum faces barriers at both the state and local levels. As seen throughout history, political and social landscape of the region dictates most of the discussion and action surrounding what curricular standards are adopted. However, “no promo homo” laws are not invincible. In 2017, Utah’s Senate Bill 0196 “repealed language prohibiting the advocacy of homosexuality in health instruction”, becoming one of the first states to repeal their “no promo homo” law in recent history. The legislation came after the group Equality Utah filed a lawsuit in Salt Lake City’s U.S. District Court, against Utah public school districts, which “asked a federal judge to strike what it calls anti-lesbian, -gay, -bisexual and -transgender curriculum laws because they are unconstitutional and violate First Amendment rights to free speech, 14th Amendment rights to equal protection and laws that prohibit sex discrimination and equal access” (Noble, 2016).

The state, and public school districts, have no real legal authority to promote heterosexuality or gender conformity in schools, just as they have no authority to promote homosexuality (Duggan, 1994; Hunter, 1993; Lugg, 2003; Rosky, 2013). Every student has a default right to be heterosexual, but every child also has the same right to identify as LGBTQ. To limit homosexual or LGBTQ-reated speech is a violation of free speech protections under the First and Fourteenth Amendments, and to limit a student’s LGBTQ status is a form of animus against them that violates the equal protection guaranteed under the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments, to targets students LGBTQ relationships (Rosky, 2013).

Two main arguments against the inclusion of LGBTQ curriculum are based on moral or religious grounds, or the grounds of the legality of homosexuality. However, including LGBTQ figures in the classroom does not infringe upon other’s right to freedom of religion and practice. In 1987, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals wrote in the curriculum case Mozert v. Hawkins, “governmental actions that merely offend or cast doubt on religious beliefs do not on that account violate free exercise” (Lugg, 2003). Parents have the right to teach their own children what they please, but they do not have the right to restrict important and vital information from their children across subjects of sciences, sociology, or psychology; students have the right to their own informed opinion (Lugg, 2003). There is also nothing inherently criminal about identifying as LGBTQ. Since Lawrence v Texas in 2003 federally overturned sodomy laws, and Obergefell v. Hodges legalized same sex marriage in 2015, homosexual identity and conduct is federally protected, even though some “no promo homo” laws still reference invalid state laws regarding these rights.

This being said, the responsibility of implementation should fall on the state and local levels, but the burden of enforcement in the face of possible legal contention should be taken up on a national level. The United States Department of Education currently does not include the words “sexual orientation” or “gender identity” in its anti discrimination policies. By adding these to the existing protection, “no promo homo” could legally be targeted as discrimination.

Conclusion

It is not only important to move towards inclusive curriculum, it is imperative to the wellbeing and education of LGBTQ identifying students. “No promo homo” laws infringe upon these students’ rights, and blatantly promote discrimination and mistreatment. LGBTQ students face significantly higher rates of harassment and miss more classes because they feel uncomfortable or unsafe. These risk factors lead to overall higher rates of negative outcomes including high dropout rates, lower rates of pursuing higher education, and higher mental illness prevalence and suicide rates. The regions where most of the “no promo homo” states lie, the south and midwest, have the highest demand for crisis intervention services provided by organizations, such as the Trevor Project, this could be attributed to the lack of other institutional supports offered at school or in the community (The Trevor Project, 2017).

All children deserve the opportunity to a safe, inclusive educational environment. LGBTQ students face numerous additional challenges in their everyday lives. In order to relieve the additional strain on these students, states must take the first proactive steps. The legality of “no promo homo” laws was challenged and overturned in Utah, and the model for inclusive curriculum has been created in California. States not only have the power to abolish these hateful practices, and implement inclusive policies, they have the obligation to do so in order to ensure the quality of education for LGBTQ students.

Works Cited

Alabama Code Title 16. Education § 16-40A-2 (1975)

Applebee, A. N. (1996). Curriculum as conversation: transforming traditions of teaching and learning. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Arizona Revised Statutes Title 15. Education § 15-716.

Athanases, S. Z., & Larrabee, T. G. (2003). Toward a consistent stance in teaching for equity: Learning to advocate for lesbian-and gay-identified youth. Teaching and Teacher Education, 19(2), 237-261.

Biegel, S., & Kuehl, S. J. (2010). Safe at school: Addressing the school environment and LGBT safety through policy and legislation.

California Department of Education. (2017, March 3). Senate Bill 48. Retrieved April 30, 2017, from http://www.cde.ca.gov/ci/cr/cf/senatebill148faq.asp

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.”Sexual Identity, Sex of Sexual Contacts, and Health-Risk Behaviors Among Students in Grades 9–12″ — Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance, Selected Sites, United States, 2001–2009. MMWR Early Release 2011;60: June 6, 2011

Duggan, L. (1994). Queering the state. Social Text, (39), 1-14.

Eskridge Jr, W. N. (2000). No promo homo: The sedimentation of antigay discourse and the channeling effect of judicial review. NYUL Rev., 75, 1327.

Gay, L., & Network, S. E. (2011). Teaching Respect: LGBT-‐Inclusive Curriculum and School Climate(Research Brief). New York, NY: Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network. Retrieved on July, 18, 2014.

Graff, G. (1993). Beyond the culture wars: how teaching the conflicts can revitalize American education. New York: W. W. Norton.

Hunter, N. D. (1993). Identity, Speech, and Equality. Virginia Law Review, 1695-1719.

Kosciw, J. G., Greytak, E. A., Giga, N. M., Villenas, C. & Danischewski, D. J. (2016).

The 2015 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth in our nation’s schools. (2015) New York: GLSEN.

Lambda Legal (n.d.) “#DontEraseUs: FAQ About Anti-LGBT Curriculum Laws.” Retrieved April 30, 2017, from http://www.lambdalegal.org/dont-erase-us/faq#Q4

Lugg, C. A. (2003). Sissies, faggots, lezzies, and dykes: Gender, sexual orientation, and a new politics of education?. Educational Administration Quarterly, 39(1), 95-134.

McGarry, R. (2013). Build a curriculum that includes everyone. Phi Delta Kappan, 94(5), 27-31.

Nash, G. B., Crabtree, C. A., & Dunn, R. E. (2000). History on trial: culture wars and the teaching of the past. New York: Vintage Books.

Noble, M. (2016, November 07). Equality Utah – In a national first, LGBT advocates sue Utah schools over ‘anti-gay’ laws. Retrieved April 30, 2017, from https://www.equalityutah.org/newsroom/item/227-in-a-national-first-lgbt-advocates-sue-utah-schools-over-anti-gay-laws

Rosky, C. J. (2013). No promo hetero: Children’s right to be queer.

Russell, S. T., & Fish, J. N. (2016). Mental health in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth. Annual review of clinical psychology, 12, 465-487.

S.B. 196, Utah (2017) (enacted).

S.B. 48, California (2011) (enacted).

Snapp, S. D., Burdge, H., Licona, A. C., Moody, R. L., & Russell, S. T. (2015). Students’ perspectives on LGBTQ-inclusive curriculum. Equity & Excellence in Education, 48(2), 249-265.

Stainback, S. (1994). Curriculum considerations in inclusive classrooms: facilitating learning for all students. Baltimore, Md: Brookes.

The Trevor Project. (2017). Retrieved April 30, 2017, from http://www.thetrevorproject.org/pages/facts-about-suicide

Toomey, R. B., McGuire, J. K., & Russell, S. T. (2012). Heteronormativity, school climates, and perceived safety for gender nonconforming peers. Journal of adolescence, 35(1), 187-196.

United States Department of Education, Office of Civil Rights. (2015, October 16). Know Your Rights. Retrieved April 30, 2017, from https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/know.html?src=ft

Wernick, L. J., Kulick, A., & Inglehart, M. H. (2013). Factors predicting student intervention when witnessing anti-LGBTQ harassment: The influence of peers, teachers, and climate. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(2), 296-301.

Zimmerman, J. (2005). Whose America?: culture wars in the public schools. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.