K12 Inc.: Virtually Failing our Students

Sydney Babiak, Emily Patton, Jaclyn Price, and Billy Roberts

Introduction

K12 Inc. is a for-profit, online education company that provides online lessons, interactive activities, and virtual classrooms for full-time students. Technically, this qualifies K12 as an Educational Management Organization (EMO) as opposed to a Charter Management Organization (CMO), which is typically nonprofit and limited to managing services, not providing them. The organization boasts of its adaptability compared to both traditional and alternative charter schools, highlighting the advantages of online education in time flexibility, socialization, curriculum, and individual learning (K12 Inc. 2017). Parent testimonials on the CMO’s website praise a challenging curriculum, with extensive student and parent support, so that even outside a traditional classroom setting, students still receive a superior education (Ibid.). As of 2011, K12 offered 49 online academies in 23 states for a total of 65,396 students (Miron et al. 2012). Critics remark that K12’s unique structure develops student responsibility through autonomy in control of schedule and pace (Ash 2012).

However, student achievement data places K12-managed charters decidedly below their district counterparts. In its position as a for-profit company, K12 pulls public dollars from local, state, and federal governments while often failing to produce results. K12 has been the recipient of public ire and various lawsuits claiming that the company has mismanaged resources and failed to put student achievement ahead of its profits. Despite attractive media and positive testimonials on official school websites, the true nature of K12’s charter schools is exposed in the numbers, which act as a Mr. Hyde to the public Dr. Jekyll that the company likes to flaunt. K12 is sucking up public dollars at a time when policymakers are itching to implement technological solutions to the nation’s issues. In this case, though, it remains doubtful that traditional schooling will ever be supplanted by online education – at least not as long as it looks like K12.

To examine this proposition, our paper evaluates data from six randomly selected K12 schools. We used ELSI, an online tool for searching through federal education statistics, to examine school demographic data recorded by the Department of Education (DOE). We also used demographic data that was recorded as part of the DOE’s Civil Rights Data Collection program. For school performance data, we looked at the school and district performance reports issued by individual states. Each of the online charters we examined was contained within a particular school district, and so all district-level comparisons are with the respective K12 school’s assigned district.

History, Pedagogy and Mission

K12 Inc. was founded in 2000 by Ronald J. Packard, a former banker and McKinsey & Co. consultant (Randall 2008). The company first took off due to $40 million in venture capital from some of Packard’s wealthy cohorts (Ibid.), and according to the chairman of K12 Inc. (and former U.S. Secretary of Education) William Bennett, the organization’s initial audience was the nation’s 1.5-2 million homeschooled children (Starr 2001). At the time of K12’s inception, many in education were exploring different options in school choice, and some believed that online learning combined corporate efficiencies with the Internet in a revolution of public education, offering high quality at lower costs (Saul 2011).

K12’s mission is to provide a superior education for individual children; the company’s website reads, “Whether your student is curious, inventive, political, analytical– or anything in between– the K12 program makes the most of each child’s unique brilliance” (K12 Inc. 2017). These schools are run in an astounding variety of ways, both in terms of management structure and curricular focus (K12 Inc. 2017). The K12 curriculum includes mostly traditional material in math, language arts, science, and social studies, and is supplemented by a Learning Coach that works with students a certain number of hours depending on their grade level (with more coaching for younger students) (Ibid.).

Demographics

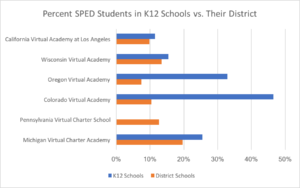

The demographic data of K12’s schools vary by state and district; however, among the six districts we examined, we were able to identify several consistent trends. Overall, our analysis indicates that K12 schools do not enroll the same demographics as other schools in their district. The students they cater to are wealthier, less diverse, and more likely to speak English than their district school peers. To their credit, K12 schools do generally exceed district schools along one demographic measure: special education; though this is likely explained by the difficulty many students face in the public school system while fighting for special education accommodations. Looking for an option that would allow them the flexibility and personal attention they need, special education students likely turn to the online charters as an educational refuge.

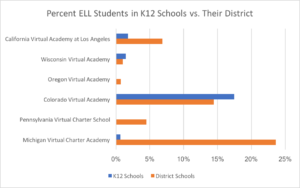

In the realm of English language learners, K12 schools consistently under-enroll. The only significant exception is Colorado Virtual Academy, and their edge over the district schools is marginal. According to a K12 representative with whom we spoke, K12 does not offer instruction in languages other than English, and Colorado Virtual Academy does not appear to be an exception according to their website. The only explanation we can think of to explain the difference is that the Colorado program offers only grades 9-12, meaning students would have likely had significant time in traditional schools to learn the necessary amount of English. The K12 schools in Pennsylvania, Michigan, and California all enroll a significantly smaller percentage of ELL students than do their districts, likely because of the exclusively English course offerings.

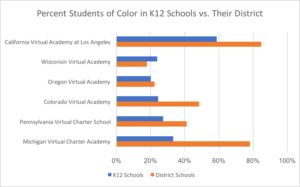

The most striking data are probably the percentages of students of color that enroll in K12 schools. In every instance except in Wisconsin and Oregon, where the white populations are a supermajority in both district and K12 schools, students of color make up a significantly smaller portion of the student body than white students.

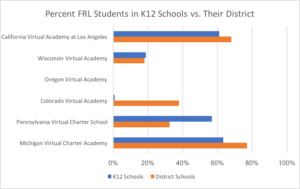

Free and reduced lunch enrollment is a bit more variable than the other demographic measures, though it still points to a more general trend wherein non-FRL students make up a greater portion of K12 schools than district schools. The outliers are Wisconsin, where the enrollments are roughly equal in proportion, and Pennsylvania, where the virtual charter enrolls a significantly greater percentage of FRL students than the district. No data was available for Oregon.

Data sources: SPED (Civil Rights Data Collection, 2013), ELL (Ibid), Race (ELSI, 2014-15), FRL (Ibid).

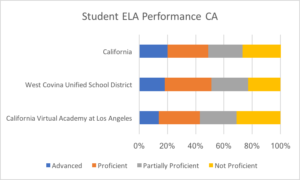

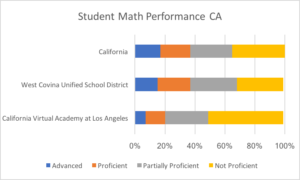

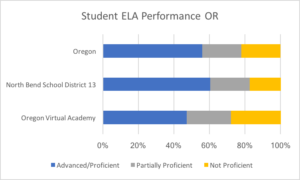

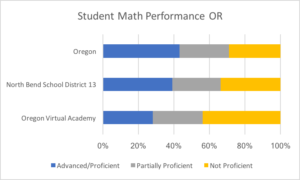

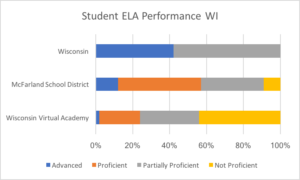

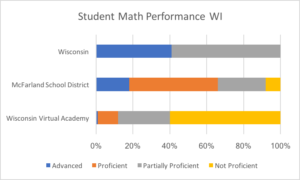

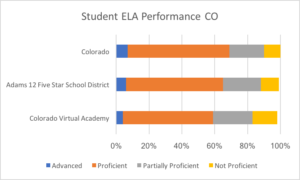

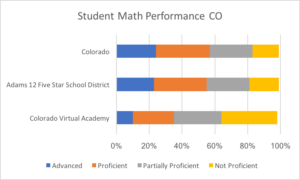

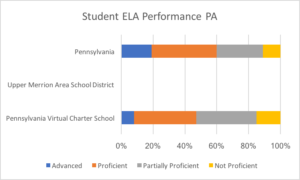

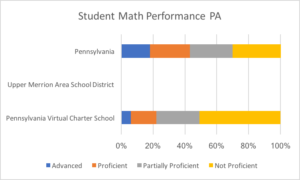

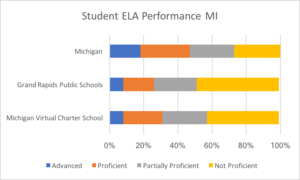

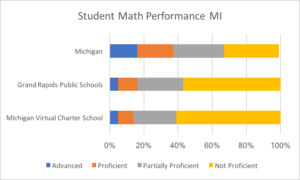

Student Performance

When it comes to student performance, the data is even more explicit in condemning K12 schools; at least in terms of the six schools that we analyzed. With no exceptions, students enrolled in K12 schools performed worse in math than their district and state counterparts. With only one exception, they performed worse in English and language arts (ELA) (though even with the one exception, Michigan Virtual Charter School, it only performed better than the district, not the state – and marginally so). Data was not available for the Upper Merion Area School District in Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin’s statewide data only had two categories: proficient and not proficient.

These data seem to make an incredibly strong case against K12’s for-profit, online charters as a way of properly educating students. It is difficult to conclude for certain, though, that the data represent some failure on the part of the schools. The poor performance could be attributable to selection bias, or the schools’ higher enrollment of special education students, or some other extraneous variable. Still, the results do not bode well for K12, and it would be wise for parents and policymakers to be wary of these schools and their analogs, unless they can somehow turn their currently abysmal performances around.

Data sources: California (California Department of Education, 2016), Oregon (Oregon Department of Education, 2015-16), Wisconsin (Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, 2015-16), Colorado (Colorado Department of Education, 2013-14), Pennsylvania (Pennsylvania Department of Education, 2016), Michigan (Michigan Department of Education, 2015-16).

Marketing and Media

K12 Inc makes bold claims of high parent satisfaction numbers, student success, and flexibility of curriculum (K12 Inc., 2017). However, according to parents, students, and teachers of K12 schools, these claims are flat-out false.

In “The Dirty Dozen,” Welner (2013) identifies several shady tactics through which charter schools endeavor to selectively recruit students. Evidence of these tactics can be found in the following aspects of K12 academy’s marketing materials:

- Descriptors of its flexibility in location: branding its services to “athletes, musicians, performers, military families, and those with physical restrictions.” (K12 Inc., 2017) This works to attract highly mobile students who often perform worse than their stable peers. (Sparks, 2017).

- Marketing targeted toward “advanced learners,” outlining their “college prep” services. This may work to recruit high performing students. (K12 Inc., 2017)

- Marketing that involves images of parents assisting the student with their work, even branding parents as “Learning Coaches.”

- In K12’s promotional “A Day in the Life” profiles, all students are pictured as receiving help throughout the day from their parents. This will exclude those students whose parents are unable to stay home due to employment. (K12 Inc., 2017).

- A lack of both curriculum in other languages and teachers able to teach in other languages. This creates barriers to potential English Language Learners’ enrollment in K12 schools (K12 Inc., 2017).

These marketing techniques not only discourage (and in some cases, preclude) some students from even applying; they also paint a dishonest picture of K12 academy schools as flexible, successful alternative choices to district schools, despite the troves of evidence to the contrary. These false marketing claims have brought about media scrutiny, but also lawsuits for K12 Inc (Saul, 2011).

In a 2011 New York Times profile of K12, the company was criticized as compromising the educational outcomes of students to increase profits, engaging in practices such as:

- Reporting enrollment numbers for students who had never logged in, thereby receiving state funds for students they weren’t teaching. State auditors in Colorado found that the K12-run Colorado Virtual Academy counted 120 students toward state reimbursement even though enrollment could not be verified and a number of students had never even logged on.

- Overworking teachers by increasing the number of students they were required to manage. One teacher from Pennsylvania said her number of students was more like 70-100, not the 1:49 student teacher ratio that K12 reported.

- Lying to shareholders, parents, students and teachers about student performance data.

- Pressuring teachers to pass students who were failing for the sake of enrollment numbers (Saul, 2011).

Additionally, while K12’s site boasts its ability to prepare students for college, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) decided in 2014 that it would not accept coursework from 24 virtual charters that use curriculum provided by K12 Inc (Raden, 2014).

The disparity between what K12 advertises and the actual lived experiences of its students, parents, and teachers has led to several lawsuits and the disappointment of a fair share of the company’s 65,000 students across the nation.

Funding

The channels through which K12 receives funding are as varied and complex as the spectrum of services it offers. With its private shareholders and largely public clients, the company to some extent beholden to what some view as conflicting mandates: the mandate to maximize profits and the mandate to maximize student achievement. This has been a talking point for K12’s skeptics, who have been particularly, who are particularly critical of the way the company handles its public funding.

In the public sector, K12 contracts out its management and educational services to independent charter schools, districts, and states. In return for these services, K12 receives the funding each of its pupils would have received from state and local governments, an average of $5,500 to $6,000 per student in addition to a share of any federal funding districts are receiving. This gives K12 Inc. tremendous control over almost every aspect of their schools including curriculum, hiring of teachers and principals, and evaluating student performance.

In addition to receiving public money through its contracts with public district and charter schools, K12 also raises revenue by selling private online courses directly to families who cannot access any of its tuition-free online public schools. The company receives additional money from corporate investors. Its stocks are publicly traded, a fact that is clearly advertised by the thorough “investors” section on the company’s website (K12 Inc, 2017).

In the years since its founding, K12 has been criticized for abusing its access to public funding by gaming the system in order to receive more money than it is entitled to. One way it has done this is to establish schools in poor districts, which may receive more funding than rich ones in some states. In 2009, K12 established a partnership with the traditional schools of Carroll County, Virginia. Though it enrolled students from across the commonwealth, all children who enrolled in the Virginia Virtual Academy were counted as Carroll County students regardless of where they lived. Because Carroll county was a poor district, K12 was able to receive extra money from the state for students who were technically coming from richer, neighboring districts (Brown and Layton, 2011).

Given founder Packard’s history in banking and consulting, it may come as no surprise that K12 has strong ties to the corporate world. The lineup of investors who helped provide him the $40 million in venture capital that he needed to start the company includes Andrew Tisch of the Loews billionaire family and Larry Ellison of Oracle and Knowledge Universe, a for-profit education conglomerate chaired by Michael Milken (Randall, 2008). The majority of the company’s executives come from for-profit education companies and other corners of the corporate world (Vogel, 2016). The head of K12’s “curriculum and products organization” previously spearheaded product development at Pearson Publishing (ibid.). Today, 87% of the company’s shares are held by institutional and mutual fund owners (Yahoo Finance, n.d.). Its top institutional investors are Technology Crossover Management VII, Ltd. and The Vanguard Group (ibid.). These connections strengthen the company’s incentive to operate with profit–rather than educational quality–as its primary motivator.

Because it receives so much public funding, K12 has also been criticized heavily for the amount of money it has channeled into non-educational ventures, particularly lobbying and advertising (Vogel, 2016). K12 has openly associated itself with the corporate-driven bill mill American Legislative Education Council (ALEC), and has contributed money to the Foundation for Excellence in Education think tank. Both of these organizations have advocated for policies that would encourage greater demand for digital learning tools like the ones produced by K12 (ibid.). To some, these activities suggest that the company has a greater interest in raising revenues and appealing to investors than it does providing quality education services for its students.

Accountability and Oversight

K12 Inc. is held accountable for its spending by both its private investors and its public clients, both of which have voiced strong objections to the company’s lack of transparency about spending.

On multiple occasions, K12’s lack of transparency regarding the way it spends student money has led charters to pull out of their contracts.

- In 2013, K12 Inc. lost a management contract with Colorado Virtual Academies—the state’s largest online charter—after complaints from parents and the school that K12 was mismanaging resources (Hood, 2013).

- In 2014, Agora Cyber Charter School in Pennsylvania, a school that accounts for 14% of the company’s $848.2 million in annual revenue decided to not to renew its management contract with K12 (Raden, 2014).

- In 2016, K12 Inc. had to pay a $160 million to 14 of its group of schools in California known as California Virtual Academies and $8.5 million to the state of California to resolve claims that the company violated California false claims, false advertising, and unfair competition laws (Kieler, 2016).

(Raden, 2014)

K12 Inc. has also faced the ire of its shareholders. In 2012, a shareholder filed a lawsuit against the company alleging that the firm violated securities law by making false statements to investors about students’ poor performance on standardized tests. This class-action suit came after chief executive Ronald J. Packard said that scores from Pennsylvania’s Agora Charter School were “significantly higher than a typical school on state administered tests for growth,” when, weeks earlier, a study found that only 42 percent of Agora students tested on grade level or better in math, compared with 75 percent of students statewide. And only 52 percent of Agora students had hit the mark in reading, compared with 72 percent statewide (Brown, 2012).

In 2011, only a third of K12-managed schools reached adequate yearly progress as mandated by the federal No Child Left Behind Program. Yet, K12 remains the largest purveyor of online schooling in the nation.

Staffing

The K12 website has little to say about the qualifications of its teachers, aside from its claim that “the majority have advanced degrees coupled with years of teaching experience (K12 Inc, 2017).” In its page on career opportunities, the company makes no specifications for the kind of candidates they are looking to hire, except to say that they are seeking “employees with creative ideas who are as committed to making a difference in education as we are (ibid).”

One qualification that all K12 teachers must share, according to the company’s website, is a thorough training in online instruction methods. At least some of this training appears to be led by the company itself, which claims to have trained “more than 5,000 teachers (K12 Inc, 2017).” In addition to this training, the website adds, “teachers go through ongoing professional development so they stay current with future advancements in online instruction (ibid).” The nature of this training is unspecified.

Because a typical online class is larger than a typical class in a brick-and-mortar school, most online teachers begin with a larger group of students than an average public school student would (Brown and Layton, 2011). This has been found to be the case for K12 teachers, some of whom have said they were managing as many as 270 students, even though they had been told they would have 150 (Saul, 2011). This is not addressed on the website, which makes no mention of either teacher sustainability or teacher diversity.

In addition to its teachers, the K12 curriculum relies heavily on the participation and cooperation of learning coaches: “usually a student’s parent or another responsible adult,” according to the website (K12, 2017). The learning coach is responsible for “ensuring their student is on track with assignments and coursework as well as communicating with their teachers throughout the school year (ibid.).”

Though learning coaches do not receive any formal training from K12, they are provided with lesson guides, tools, videos and resources to talk to other parents of other current students (ibid.). According to the K12 website, the time commitment of the learning coach is expected to decrease as grade levels increase. Notably, in what is perhaps its only indirect nod to the possibility of ELL learners, the website also points out that “learning coaches are not required to be fluent in English (ibid.).”

Relationship to district

As the complicated nature of its funding would suggest, the relationship between K12 schools and their surrounding districts has the potential to be highly fraught, particularly when they are competing with district schools for public funding. In in 2008, Forbes reported that “when students abandon the blackboard for the flat screen, their schools lose up to 70% of the taxpayer money that attaches to them (Randall, 2008).” This can pose a significant problem for district schools, especially when the state counts all enrolled students as residents of the district where the charter school is established, as they did in Carrol County.

Other impacts of K12 schools may be slightly more obscure, given the myriad of ways in which their services can be implemented. K12 schools are either categorized as a Virtual Academy, which uses traditional K12 curriculum; an Insight School, which specializes in helping students overcome certain learning challenges; a blended school that combines classroom attendance with online learning; a Destination Careers Academy, which emphasizes college and career preparation; and finally, a District-Run School, where traditional public schools incorporate K12 curriculum in their classrooms using available technology (K12, 2017). The sheer variety of these options makes it difficult to distinguish or even speculate on the overall effect that a K12 school might have on the environment in which it is situated.

Conclusion

While K12 Inc. may have started out as an effort to bring public education into the 21st century with corporate efficiency and online curriculum, giving students across the nation the chance to learn what they might in a brick-and-mortar public school from home, it has since failed to produce satisfactory results. In fact, every virtual charter in the districts studied performed worse than their respective district schools.

Policymakers should be mindful of K12 Inc.’s abysmal track record of failing its students, recruiting only a narrow selection of students while accepting government dollars, lying to shareholders, and serving monetary interests before students. K12 has done everything within its power to increase profits while mismanaging public education resources taken away from district schools.

Bibliography

2016 PSSA State Level Data; 2016 PSSA School Level Data (2016). Data Files, Pennsylvania School Performance Profile, Pennsylvania Department of Education. Online. March 31, 2017.

Ash, Katie. “Flexibility, Support Build Student Independence.” Education Week, October 14, 2012.

Civil Rights Data Collection (2013). U.S. Department of Education. Online. March 5, 2017.

“Day In A Life – A day in the life of three online students.” K12. Accessed March 31, 2017.

ELSI (2014-15). National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education. Online. March 5, 2017.

High School Assessments: Proficiency Snapshots (2015-16). Student Assessment, MI School Data. Center for Educational Performance and Information, Michigan Department of Education. Online. March 31, 2017.

Hood, Grace . “COVA, K12 Inc. To Part Ways As New Online School Is Proposed [Updated].” KUNC. June 11, 2013. Accessed March 31, 2017.

“K12 Inc. (LRN) Major Holders” Yahoo Finance. Accessed April 04, 2017. http://finance.yahoo.com/quote/LRN/holders?p=LRN.

K12 Inc. “Tuition-Free Online & Virtual Public Schools.” Last modified 2017. http://www.k12.com/k12-schools/free-online-public-schools.html.

K12 Inc. “Online Course Curriculum.” Last modified 2017. http://www.k12.com/curriculum.html.

K12 Inc. “Investor Overview.” Last modified 2017. http://investors.k12.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=214389&p=irol-IRHome&_ga=1.174947041.291223893.1488908162.

K12 Inc. “Teachers.” Last modified 2017. http://www.k12.com/k12-education/teachers.html.

K12 Inc. “Who We Are.” Last modified 2017. http://www.k12.com/.

K12 Inc. “Testimonials.” Last modified 2017. http://www.k12.com/k12-education/testimonials.html.

K12 Inc. “Student Success.” Last modified 2017. http://www.k12.com/k12-education/student-success.html.

Kieler, Ashlee. “Online Charter School K12 Hit With $169M Settlement For False Advertising Allegations.” Consumerist. September 29, 2016. Accessed March 31, 2017.

Miron, Gary and Jessica L. Urschel, Mayra A. Yat Aguilar, Breanna Dailey. “Profiles of Nonprofit and For-Profit Education Management Organizations.” National Education Policy Center, January 2012.

“Online Public School, Online High School, Online Private School, Homeschooling, and Online Courses options.” K12. Accessed March 31, 2017.

Oregon Virtual Academy; North Bend School District 13 (2015-16). School and District Report Cards, Oregon Department of Education. Online. March 31, 2017.

Raden, Bill. “Cyber Charter School Revolt Against K12 Inc. Continues – Capital & Main.” Capital & Main. September 3, 2014. Accessed March 31, 2017.

Randall, David K. “Virtual Schools, Real Business.” Forbes, July 24, 2008.

Saul, Stephanie. “Profits and Questions at Online Charter Schools.” The New York Times, December 12, 2011.

SchoolView Data Lab Report (2013-14). Colorado Department of Education. Online. March 31, 2017.

Search Smarter Balanced Test Results (2016). California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress, California Department of Education. Online. March 31, 2017.

Sparks, Sarah. “Student Mobility: How It Affects Learning.” Education Week. March 10, 2017. Accessed April 04, 2017. http://www.edweek.org/ew/issues/student-mobility/.

Starr, Alexandra. “Bill Bennet: The Education of an E-School Skeptic.” Bloomberg, February 14, 2001.

Welner, K. G. “The Dirty Dozen: How Charter Schools Influence Student Enrollment.” Teachers College Record. April 2013.

WIVA Hi, School Report Card Detail; McFarland, District Report Card Detail (2015-16). Accountability Report Cards, Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction. Online. March 31, 2017.

Vogel, Pam. “Here Are The Corporations And Right-Wing Funders Backing The Education Reform Movement.” Media Matters for America. April 22, 2016. Accessed April 04, 2017. https://mediamatters.org/research/2016/04/27/here-are-corporations-and-right-wing-funders-backing-education-reform-movement/210054#k12.