Sydney Babiak

Edgar Aviña

PLSC 240/EDST 245 Public Schools & Public Policy

Introduction

Estimates suggest that more than 7 million children in the United States are without adult supervision for at least some period of time after school. 800,000 elementary school and 2.2 million middle school students are on their own when they leave school (“Taking a Deeper Dive” 4). This unsupervised time puts children at risk for negative outcomes such as academic and behavioral problems, drug use and other types of risky behavior, yet schools with a need to slash costs in an era of constrained budgets often choose to scrap their afterschool programming. Many schools and districts rationalize these cuts by arguing that afterschool programs just do not generate enough payoffs to justify the costs of programming and personnel.

Contrary to this logic, hundreds of studies have documented the positive and statistically significant effects of afterschool programming on academic achievement (“Taking a Deeper Dive” 4) . However, the effects of afterschool programming on social and behavioral skills have received much less attention, in part because measuring progress on social and behavioral skills is more difficult, but also because it has just been relatively under-discussed among most scholars until recently.

This paper argues that afterschool programs that focus on social and behavioral skills are more beneficial to students than those that focus on academics. We will also highlight one framework for structuring afterschool programming that will successfully help children cultivate strong social and behavioral skills, which we are defining as “the cognitive, affective, and behavioral competencies necessary for a young person to be successful in school, work, and life” (“Supporting Social and Emotional Development Through Quality Afterschool Programs” 2). We hope that this paper will help contribute to the conversation about what well-designed afterschool programming focusing on social and behavioral skills might look like. While other studies have examined the positive outcomes of programs that focuses on social and behavioral skills, this report is the first to connect these successes to a specific framework of instruction and curriculum. The need for afterschool programming is ubiquitous, and we must work diligently to create quality programs that genuinely help advance student social and behavioral skills.

Methods

For this report, we researched current strategies in afterschool programming and chose a particular design that we wanted to highlight as potentially impactful. We then used data from studies at various universities and organizations. Many of the projects we pulled from did not answer our questions or implement the CASEL structure exactly, but usually had information on some component of either the effectiveness of afterschool programs, social and behavioral curriculum, or active engagement with students that we could then conceptually connect with the model we were highlighting. We then chose two afterschool programs we found details about within a few of our more comprehensive sources and analyzed their engagement with our the CASEL framework. We designed a few graphics using Google Sheets and the SmartArt functionality in Microsoft Word in order to better illustrate some of our points.

The CASEL Framework of Instruction and Curriculum

CASEL has analyzed dozens of afterschool programs over the past two decades, and has developed their own proposal for how to structure an afterschool program that meaningfully enhances social and behavioral skills. This framework has two parts: SAFE, the methods by which instruction should be given, and the CASEL competency clusters, which are the recommended focus points for the instruction. Each will be presented in turn below.

Figure 1 is a visual representation of how the framework is supposed to operate. All afterschool programs using the CASEL frameworks should have the same instructional strategies (the SAFE method), but each might focus on one or more CASEL competency in particular.

Figure 1

A visual representation of the CASEL Framework of afterschool programming

SAFE

In 2004, CASEL analyzed 73 afterschool programs and found a series of four structural qualities that effective afterschool programming requires to achieve substantive gains in social and behavioral skills. An effective program must be Sequential, Active, Focused, and Explicit.

Programs must be Sequential because new social and behavioral skills cannot be acquired instantaneously (Durlak and Weissberg, “The Impact of Afterschool” 28). Social and behavioral skills are complex, which means that they have to be broken down into smaller components that can be taught sequentially with an ultimately cumulative end goal. Teaching must be linear, and follow a logical progression.

Programs must be Active because students are entering afterschool programs after a full day of regular school, which can mean they will be easily antsy, bored, and distracted. To ensure student engagement, the teaching must be active and involved; students should not be sitting in a room being lectured to when they have already endured a full day of schooling. Moreover, evidence indicates that youth learn best from active engagement where they have chances to practice new behaviors and receive feedback on their performance (Protheroe 3), such as practicing social and behavioral skills through “role playing and other types of behavioral rehearsal strategies” (Durlak and Weissberg, “The Impact of Afterschool” 26), for example. A sequence of practice and feedback should continue until mastery is achieved. Hands-on forms of learning are much preferred over exclusively didactic instruction, which rarely translates into long-term learning (Durlak and Weissberg, “The Impact of Afterschool” 28).

Afterschool programming must be also be Focused on social and behavioral skills—teaching on the development of these skills cannot be merely interspersed sporadically in the program. Many afterschool programs fail to inculcate students with valuable skills precisely because they do not develop focused programming that addresses specific growth areas for students, but rather just operate without any particular direction or goals. Moreover, the content of the programming must be Explicit in communicating to students clearly what the learning objective is. If the goal is to improve self-esteem, that goal must be communicated clearly to students.

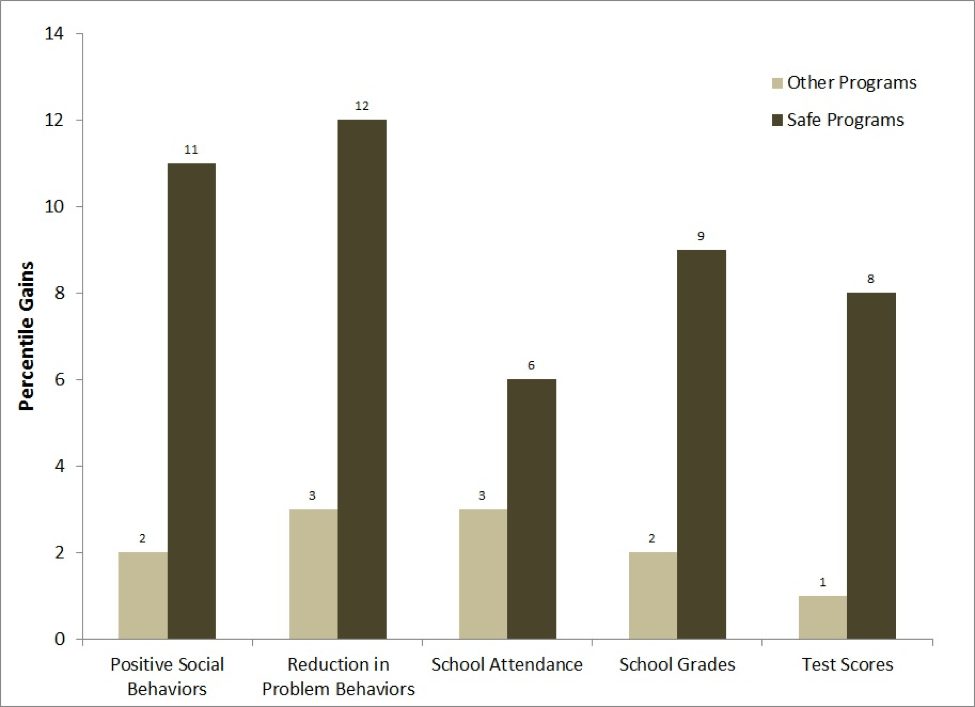

SAFE has proven particularly effective in increasing self-esteem, self-efficacy , improved attitudes toward self and school, and social and communication skills. Figure 2 shows data collected by CASEL on the observed positive benefits of programs that used the SAFE methods and those that did not.

Figure 2

Average percentile gains on selected outcomes for participants in SAFE and Other Afterschool Programs

CASEL Competencies

In their research brief titled Supporting Social and Emotional Development Through Quality Afterschool Programs, CASEL defines five competency clusters that they found critical for young people’s success in school, work, and life (Devaney 2):

- Self-awareness: the ability to understand one’s emotions, and how these emotions influence behavior

- Self-management: the ability to calm down when upset, set and work towards goals, and to manage/control emotions

- Social awareness: the ability to recognize what’s appropriate in certain settings, and to empathize with others

- Responsible decision making: the ability to make decisions that account for social standards, consequences, and context

- Relationship skills: the ability to communicate well, listen and respond appropriately, and to negotiate conflict

CASEL believes these competencies can be taught through explicit curricula or school/classroom-wide interventions that integrate them into every aspect of the school day, such as through collaborative projects in class or facilitated activities at recess. The research brief emphasizes that afterschool programs can do either, and that the best of these programs will teach these use this framework to instill grit, self-control, and growth in its participants (Devaney 4). CASEL’s study also found that consistent participation in programs using SAFE and the CASEL framework led to improvements in peer relationships, sense of self-worth, altruism, prosocial behavior, and decreased problematic behavior (Devaney 5).

Other analyses of afterschool programs with similar frameworks (that emphasize the same competencies but do not explicitly associate with CASEL) also found overwhelmingly positive results with regards to social and behavioral outcomes. Several studies at the School of Education at UC Irvine, like their peers at CASEL, also saw improvements in peer relationships and prosocial behavior, in addition to progress in engagement, intrinsic motivation, concentrated effort, and positive mindsets (Devaney 5).

The Youth Development Research Project at the University of Illinois also reported impressive effort and engagement in their analyses:

…youth report building skills in motivation and effort from participating in youth programs– in particular, youth voluntarily engage in challenging work in youth programs, are committed to completing the work, and therefore put in the effort and make the connection between hard work and results. Youth then learn these behaviors and can engage in strategic thinking and persistent behavior outside the youth program. (Devaney 5)

Collectively, these studies all provide evidence of how concerted focus on key non-academic characteristics in an afterschool program can lead to the development of crucial skills for not only a student’s academics, but for their life to come. This dual benefit is largely what makes afterschool programs that center around social and behavioral learning more fruitful and efficient than their counterparts.

Data

Recent studies provide quantitative evidence that participation in programs that focus on the CASEL competency clusters and use the SAFE method of instruction– rather than just focusing on academics– yield improvements in social and behavioral skills. As discussed previously, these skills are critical for a young person’s success in school, work, and life.

A study of 73 afterschool programs that targeted personal and social skills found that “solid” training approaches included sequenced activities to achieve skill objectives, active learning, and explicit focus on personal or social skills. According to the study, “These programs showed significant positive benefits in terms of student self-confidence, positive social behaviors, and achievement test scores” (David 84). Other observed programs that did not use these same approaches did not produce improvement in any of these outcomes (David 84). The researchers in this study maintain that, “…programs without an academic component can nevertheless demonstrate increases in student achievement, whereas many programs focused on achievement fail to do so” (David 85). Therein we see why afterschool programs must begin to shift their focus towards developing fundamental social and behavioral skills first before approaching academics: building the blocks of sustainable interpersonal aptitudes in young children will set the stage for success in school both immediately and for the rest of a student’s academic career.

A report from Joseph A. Durlak and Roger P. Weissberg reviewed 68 studies on afterschool programs with specific goals of fostering personal and social development (CASEL competencies) compared to control groups of non-participating youth (“Afterschool Programs” 2). Table 1 compares the mean effect sizes of the experimental (SAFE-modeled programs focused on social and behavioral development) and these control groups (Durlak and Weissberg, “Afterschool Programs” 3). The data shows significant positive outcomes for students in afterschool programs that use the CASEL framework compared to those that do not, with particular advantages in school bonding, self-perceptions, and positive social behaviors.

Table 1

The mean effect size of student behaviors in experimental and control groups (Durlak and Weissberg 3)

| Mean effect size of SAFE Programming | Mean effect size of control | |

| Drug use | .16 | .03 |

| Positive social behaviors | .29 | .06 |

| Reduction in problem behaviors | .30 | .08 |

| School attendance | .14 | .07 |

| School bonding | .25 | .03 |

| School grades | .22 | .05 |

| Self-perceptions | .37 | .13 |

| Academic achievement (test scores) | .20 | .02 |

Table 2 shows the value-added benefit of afterschool programs that focused on one or more personal or social skills, measuring how many more youth would benefit from participation in these programs compared to participation in other, nonfocused programs. It is calculated by dividing the difference between the improvement rates of participating and control youth by the control improvement rate ((A-B)/B). The data was collected by Joseph A. Dorlak and Roger P. Weissberg for their report, The Impact of After-School Programs That Promote

Personal and Social Skills.

Table 2

The Value-Added Benefits of Effective Afterschool Programs (Durlak and Weissberg, “The Impact of Afterschool” 18)

| Outcomes | % of Program Participants Improving (A) | % of Controls Improving (B) | Value-Added % Benefit |

| Feelings and Attitudes (child self perceptions, school bonding) | 58.75, 56.5 | 41, 43.5 | 42.6, 29.8 |

| Indicators of Behavioral Adjustment (positive social behaviors, problem behaviors, drug use) | 57.5, 56.5, 55.5 | 42.5, 43.5, 44.5 | 35.2, 29.8, 24.7 |

| School Performance (achievement tests, school grades) | 57.75, 56 | 42.25, 44 | 36.6, 27 |

This data provides more evidence that participation in programs focused on social and behavioral development can lead to improvements in three key areas of a child’s education: attitude, behavior, and academic performance.

Examples

This section presents two successful afterschool programs that focus on social and behavioral skills instead of academic performance. It also demonstrates how their adherence to the CASEL framework of the SAFE method of instruction in coordination with a focus on one or more of the CASEL competency clusters has enabled their success.

Woodrock Youth Development Program

The Woodrock Youth Development Program is a highly-structured afterschool program in Kensington, Philadelphia—a long-struggling neighborhood that harbors over 40% of the drug trade in the whole city (“A Profile]”)— that has improved student social and behavioral skills by adhering to the CASEL framework.

The core of the program is a series of weekly human relations classes. Each class is conducted by a team of two youth advocates, who represent different racial, ethnic, and gender backgrounds. Classroom activities focus on raising awareness about the dangers of substance abuse, “fostering self-esteem through enhancing images of racial membership groups,” and developing an appreciation of other ethnic and cultural traditions (“A Profile”). The curriculum is sequenced and active, with periods for open discussion and role-playing exercises weaved into every lesson. The programming is also focused, in that every class very explicitly addresses a certain kind of skill that it wants its students to develop (LoScutio).

The program has improved student outcomes along several dimensions, as shown by the data in the table below, which measures how much participating students improved over non-participating students. Participants were very similar to non-participants in terms of race, socioeconomic status, and achievement.

Table 3

Woodrock Youth Development Program – Standard deviations in student outcomes for participating and non-participating youth in social and behavioral skills (“A Profile”)

| Skill | Effect Size (in standard deviations) |

| School Attendance Rates | .22 |

| Drug Use Reduction | .19 |

| Increased Racial Tolerance | .22 |

| Self-esteem | .13 |

| Reduction in Aggression | .19 (not statistically significant, p = .09) |

The Woodrock Youth Development Program does not explicitly align itself with the CASEL framework, but its teaching and structure strongly model it. The results from this program, which works with some of the most troubled students in the country, are promising, and hint at the potential power of rolling out a full-fledged SAFE programming with CASEL competency clusters.

Maryland After-School Community Grant Program

The Maryland After-School Community Grant Program is an afterschool program in Baltimore, Maryland, funded by the Maryland Governor’s Office of Crime Control and Prevention with additional federal funds from the U.S. Department of Justice (Zief et al. 43). The program is run by school teachers, the principal, a guidance counselor, a police officer, and student volunteers, and lists two major goals: to lower delinquency and drug use among its students (Zief et al. 44). The program coordinators also report a minor focus on other tangential qualities, such as decreasing negative peer influence and improving social skills (Zief et al. 44).

The Maryland After-School Community Grant Program does not claim to follow the CASEL framework of programming, but nonetheless fits the model in many ways. The program provides academic and social skills instruction, which are presumably focused and explicit, along with additional recreational offerings such as board and video games, pool and ping-pong, and organized sports; these activities account for the “active” component of the SAFE method (Zief et al. 45). Our source does not mention any sequential element to the program’s instruction, which means we can neither confirm nor deny if it employs this last component of SAFE.

The positive results (with significance of p<0.5) seen when studying this program included more time spent with positive peer groups, a decrease in negative peer influences, and increased involvement in constructive activities (Zief et al. 49). However, participants also spent less time in self-care (Zief et al. 47). We speculate that this may be a result of constant instruction and activities in addition to the regular school day– students may not feel the need or feel entitled to take personal times for themselves and their overall happiness.

While the Maryland After-School Community Grant Program is not perfect, it provides an example of some positive results that can come from afterschool programs with directed focus and active engagement. There are many areas where the program could improve, such as with more explicit focus on the CASEL recommended competencies, but nonetheless, their structure has seen solid outcomes in important areas that will benefit these kids far beyond their lives as students.

Discussion

Overall, we see the CASEL framework often creates positive change in students that consistently participate in afterschool programs, even if some programs do not know they are necessarily adhering by the guidelines of this particular structure. The important characteristics extracted from the data and examples show that programs with concise focus on social and behavioral abilities, coupled with active and sequential activities to engage with these skills, can enact positive change that gives kids tools to succeed not only in school, but also for the rest of their lives.

Research has shown that afterschool programs that focus on social and behavioral development yield positive benefits not only in the targeted skills, but also in academic success, which proves why more programs should begin shifting their goals to revolve around these characteristics rather than just improved academics. While success in school is important, it can often be fleeting and unsustainable, whereas characteristics such as persistence and self-control are crucial qualities that have been proven to aid classroom achievement as well (in many cases more successfully than programs that only focus on academics).

For this reason, we believe that afterschool programs should abide by the CASEL framework: structured and operated according to the SAFE model, with emphasis on at least one component of the CASEL competency clusters of self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, responsible decision-making, or relationship skills. While not much research has been done on programs with this structure (mostly because not many yet exist), we maintain that if all afterschool programs can establish strong building blocks in these core areas, success in academics, social situations, and their future life endeavors will come far easier.

Addressing Challenges: Embedded Influence and Attendance

It is important to recognize that even the best-planned program aligned perfectly with the CASEL Framework can still face challenges. The most salient challenge is the issue of student retention: how do you ensure that students maintain continuous attendance? Scholar Ingrid Nelson develops a theory of embedded influence that posits that there are many overlapping and evolving contexts of students’ homes, schools, and communities that can inhibit student attendance (160). Nelson recognizes that participants’ and their social situations change over time, and thus acknowledges that afterschool programming will affect the same student in different ways depending on their situation at home and in their personal lives. For example, a middle school student that is an avid participant in middle school of afterschool programming may drop it all together once she needs to work a job in high school.

The issue of attendance is difficult to solve because of embedded influence and other systems that influence student behavior, but all programs must be conscious of this challenge as they structure their program. A possible method of addressing this challenge would be to mandate attendance, as the Woodrock Youth Development Program does. Tackling logistical challenges can also help increase consistent attendance. For example, something as simple as providing car rides or bus rides to students who struggle to get home after afterschool programming could play a huge role in increasing long-term participation.

We did not address attendance in our outlining of the CASEL framework, because data on attendance was not relayed in our sources. Had we been able to collect our own data, we would have measured attendance patterns against the successes of afterschool programs to identify any possible causal relationships. The issue of attendance is a huge gap in the research that is ripe for more exploration.

Conclusion

Overall, we believe that an afterschool program that is structured according to the CASEL Framework SAFE method and centers around one or more of CASEL competencies is the best design for students. We came to this conclusion after an analysis of the early research and data obtained on this relatively under-studied topic, along with some hypothesizing on our own end. We see the CASEL competencies as fundamental characteristics necessary for a child’s imminent success in school, relationships, and life, and the SAFE design of instruction gives programs a structure to follow that has seen quantified success.

Works Cited

“A Profile of the Evaluation of Woodrock Youth Development Project.” Harvard Family Research Project, 2017. Web. 01 May 2017. http://hfrp.org/out-of-school-time/ost-database-bibliography/database/woodrock-youth-development-project

David, Jane L. “Research Says…After-School Programs Can Pay Off.” Educational Leadership, vol. 68, no. 8, 2011, pp. 84-85. Web. http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational_leadership/may11/vol68/num08/After-School_Programs_Can_Pay_Off.aspx.

“Taking a Deeper Dive into Afterschool: Positive Outcomes and Promising Practices.” Afterschool Alliance. Feb. 2014. Web.http://www.afterschoolalliance.org/documents/Deeper_Dive_into_Afterschool.pdf.

Devaney, Elizabeth. Supporting Social and Emotional Development Through Quality Afterschool Programs. Chicago: Beyond the Bell at American Institutes for Research, 2015. Web. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED563826.pdf.

Devaney, Elizabeth, and Deborah Moroney. Linking Schools and Afterschool Through Social and Emotional Learning: Research to Action in the Afterschool and Expanded Learning

Field. Chicago: Beyond the Bell at American Institutes for Research, 2015. Web. http://www.air.org/sites/default/files/downloads/report/Linking-Schools-and-Afterschool-Through-SEL-rev.pdf.

Durlak, Joseph A., and Roger P. Weissberg. Afterschool Programs that Follow Evidence-Based Practices to Promote Social and Emotional Development Are Effective. Chicago: C.S. Mott Foundation, 2016. Web. http://www.expandinglearning.org/docs/Durlak&Weissberg_Final.pdf.

Durlak, Joseph A., and Roger P. Weissberg. The Impact of After-School Programs That Promote Personal and Social Skills. Chicago: Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, 2007. Web. http://www.casel.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/the-impact-of-after-school-programs-that-promote-personal-and-social-skills.pdf.

LoSciuto, Leonardo, Susan M. Hilbert, M. Margaretta Fox, Lorraine Porcellini, Alden Lanphear. “A Two-Year Evaluation of the Woodrock Youth Development Project.” Journal of Early Adolescence, vol. 19, no. 4, 1999, pp. 488-507. Web. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0272431699019004004.

Nelson, Ingrid A. Why Afterschool Matters. Rutgers University Press, 2016. Print.

Protheroe, Nancy. “Successful After-school Programs.” National Association of Elementary School Principals, May 2006. Web. https://www.naesp.org/resources/2/Principal/2006/M-Jp34.pdf

Vandell, Deborah Lowe, and Elisabeth R. Reisner, Kim M. Pierce. Outcomes Linked to High-Quality Afterschool Programs: Longitudinal Findings for the Study of Promising Afterschool Programs. Irvine: University of California, Irvine, 2007. Web. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED499113.pdf.

Zief, Susan Goerlich, and Sherri Lauver, Rebecca A. Maynard. Impact of After-School Programs on Student Outcomes. Oslo: Campbell Systematic Reviews, 2006. Web. https://www.campbellcollaboration.org/media/k2/attachments/1011_R.pdf.

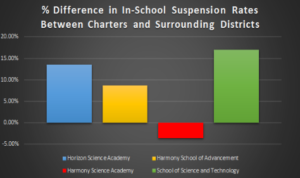

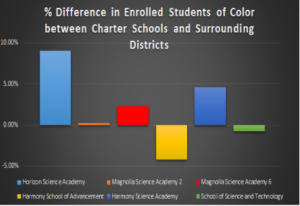

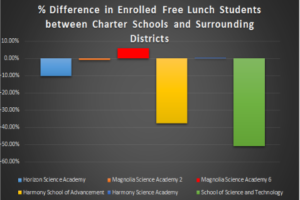

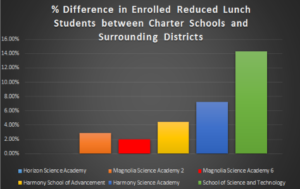

A comparison of the free and reduced lunch data of Gulen schools and their surrounding districts makes it clear that Gulen Schools are

A comparison of the free and reduced lunch data of Gulen schools and their surrounding districts makes it clear that Gulen Schools are  om the fact that Gulen schools enroll much fewer

om the fact that Gulen schools enroll much fewer