Daniel Vernick, May 2017

Fighting for a Future: The Massachusetts ‘No on 2’ Campaign and Its Impact on Public Education Advocacy

Executive Summary

The efforts of the Massachusetts Teachers Association (MTA), the main teacher union in MA and the central organizer of the 2016 anti-charter campaign, were instrumental to the success of the No on question 2 campaign. The campaign was a success due to its grassroots field operation, effective messaging, and community-based support, and can serve as a model for the public education movement in Massachusetts and across the country.

Introduction

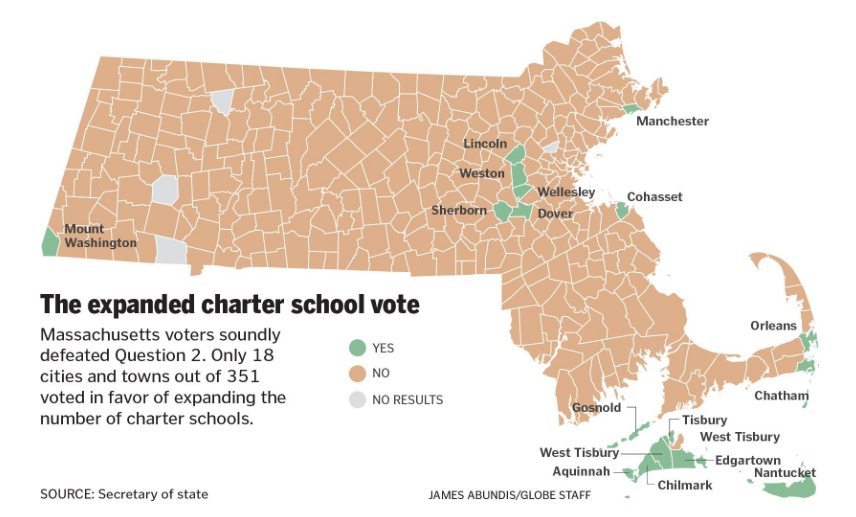

In 2009, the MTA compromised on a deal in the MA legislature to raise the cap on charter schools. They did so because if the bill failed, it would go to a ballot measure – and, in a national atmosphere in which support for charters was rising among both Republicans and Democrats as well as championed by the Obama administration, the union leaders were convinced that such a ballot measure would pass and leave lasting damage on Massachusetts’ public schools. This changed with the election of Barbara Madeloni as MTA President. Madeloni believed in an forcefully progressive approach, a strategy that ended up working. Fast forward to 2016, and Madeloni decided to embrace the anti-charter campaign. According to the polls, which showed a landslide victory for the pro-charter side, many said she should invest union resources elsewhere. Question 2 ended up being defeated 62-38. The result was not only a landslide in public support away from charters but also a landslide of questions for pro-charter advocates, whose strategies largely failed. The result rejuvenated public education advocates and provides a route of resistance against the charter lobby that once seemed too powerful to resist, which is particularly relevant in the Trump-DeVos era.

Background

When Madeloni was elected, the MA legislature in 2014 was again about to raise the charter cap. Madeloni “urged her rank and file” to resist lifting the cap, which succeeded and showed the potential for grassroots organizing among public education advocates. The potential for a referendum was viewed as negotiating tool by the pro-charter side because it would allow for such a dramatic expansion in charters.[1] MA State Senate ended up passing the Rise Act, which tied charter cap increases to an increase in local education funding for 7 years and would cost 203-212 million per year.[2] The House decided not to compromise with the Senate on the bill and instead leave charters up to the voters, setting off the 2016 ballot campaign.

Madeloni’s willingness to take such a controversial issue head-on and success at mobilizing her membership was crucial. The result was that “teachers came out in force to talk to their neighbors,” and most people place high trust in teachers. One teacher said that their “neighbors looked to [teachers] as authorities on the issues involved in the ballot question, and greeted them warmly when approached to discuss” the anti-charter campaign[3] – a starkly different reaction than most political canvassers receive.

There are currently 78 charters in MA.[4] The current charter cap allows for 120, with 4-5 approved each year. The cap also includes a limit on the percentage of school budget spent on charters, preventing districts from spending more than 9% of their budget–and 18% in low-performing districts–on charters. In cities such as Boston, Lowell, and Springfield, the financial limit has resulted in waiting lists. In 2010, a “smart cap” was instituted. This prioritizes charter applications from CMOs “with a proven track record that seek to expand in low-performing districts.” Still, the charter cap has limited charters in many cities, with tens of thousands of students on waitlists.[5] Question 2 would allow an additional 12 charters per year for an unlimited number of years.

Top in the Nation: Massachusetts Charter Schools

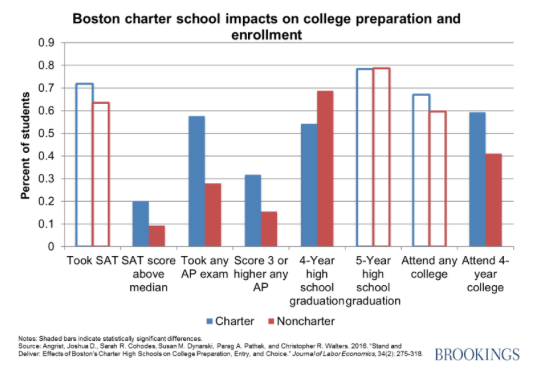

The pro-charter campaign centered on the fact that MA charters are some of the highest performing in the nation and have avoided the scandals than plauge those in other states. A recent Brookings report claims that MA urban charters have positive student outcomes and increase the performance of low-performing students. The MA charter application process “is one of the most rigorous in the country,” which is shown by the closure of 17 charter schools “deemed ineffective or mismanaged” since 1997.[6]

DESE reviews all applications for MA charters. This centralized system allows for universal standards to hold charters accountable and is starkly different from other states, allowing for high performance.[7] Attending a Boston charter for one year results in a substantial increase in test performance and eliminates 1/3 of the “racial achievement gap.”[8] Competition among charters is part of the reason why MA charters are high-performing, and therefore the anti-charter side argued that drastically decreasing competition would have negative effects on charter quality.

“Great Schools” or “Save Our Public Schools”: Campaign Messaging and Arguments

Charter supporters planned a three part strategy. First was the legislative effort, then a ballot question, and the third alternative was a lawsuit using an elite Boston law firm to “file a class-action suit to lift the charter cap” because “it unconstitutionally denies children access to an adequate education.”[9] Great Schools MA was the umbrella pro-charter campaign committee. Families for Excellent Schools (FES) was the primary organization under the umbrella. FES is a “powerful pro-charter force in NYC,” and opened a branch in MA solely to lobby for question 2. FES is funded by Wall Street donors, many of whom would benefit financially from increased charters. It claims to be grassroots and parent-based, but the reality is that “a small group of charter school chains, politically connected Wall Street financiers, and powerful education officials have controlled FES since its founding.”[10] In New York, FES organized public displays of pro-charter activism, such as 30,000 people marching across the Brooklyn Bridge; “theirs is a powerful spectacle, until one looks too closely and notices that the guys on the walkie talkies are all white and that the parents were told that they had to attend.”[11] MA Secretary of Education James Peyser was on the board of FES as well as a “managing partner of New School Venture Fund,” which is “among the first and largest investors in charter schools and the first to support multi-site” CMOs. Therefore he had a direct interest in passing question 2. Furthermore, as Executive Director of the Pioneer Institute, Peyser also “helped craft a strategy for the charter expansion forces” in MA.[12] FES failed due to its vague messaging that shied away from explicitly stating its goal of pushing charters, instead beginning its work in Boston with a “lavishly choreographed rally” at Faneuil Hall. The rally did not mention charter schools at all.[13]

There were also Massachusetts-based groups under the Great Schools MA umbrella. Democrats for Education Reform (DFER) and the MA Charter Public School Association both poured in money. DFER’s first ominous sign occurred in the September 9th Democratic primary for a State Senate seat in Cambridge and Somerville. The race pitted anti-charter State Senator Pat Jehlen against pro-charter Cambridge City Councilor Leland Cheung. Cheung was closely connected with DFER, who funded his campaign. In response, MTA contributed a smaller amount to Jehlen’s campaign. Jehlen challenged DFER President Liam Kerr to a debate, stating that Kerr is her real opponent. Kerr agreed, and the election became a referendum on charter schools. Cheung ended up losing with just 20% of the vote to Jehlen’s 80%. DFER and the pro-charter lobby claimed that this vote was an outlier that did not represent the opinion of MA voters. Yet they made very similar statements after losing question 2; there is a clear trend and roadmap to oppose charters. These are not isolated losses, but rather a growing fundamental distrust of charter schools that will further manifest itself in the coming years.

The pro-charter campaign kept switching tactics, unable to settle on a central message that worked. Its chaotic messaging contrasted with the No campaign’s straightforward and concrete central message of district school funds being funneled to charters. That argument was reinforced by the hundreds of School Committees across MA that passed resolutions opposing question 2 because they knew firsthand how much money was lost to charters. As polls showed the yes side losing, the Yes side began to directly contradict the No side’s argument, “airing ads saying that charter schools would provide more money for public education.”[14] Another central pro-charter campaign argument was the waitlist, which changed during the campaign due to the MA Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE) releasing a waitlist number that was artificially high. State Auditor Suzanne Bump said that “DESE had overstated the waitlist by an indeterminable amount by rolling over entries from prior years who may no longer be interested.”[15] Not everyone on a waitlist actually wants to go to that school; often students are placed on multiple waitlists so that parents retain a variety of options.[16] Normal public schools also have waiting lists, particularly in places like Boston. These waitlists are unable to “be as expansive as charter waitlists, since they’re only held till January” and do not roll over.[17] Since MA was ranked first in student achievement, and also because 96% of public school students in MA attend normal public schools, voters were generally positive toward the MA education system.[18] MA Parent Teacher Association and MA Municipal Association both officially opposed question 2.[19] These are well-respected and nonpartisan organizations that send a message of bipartisan opposition.

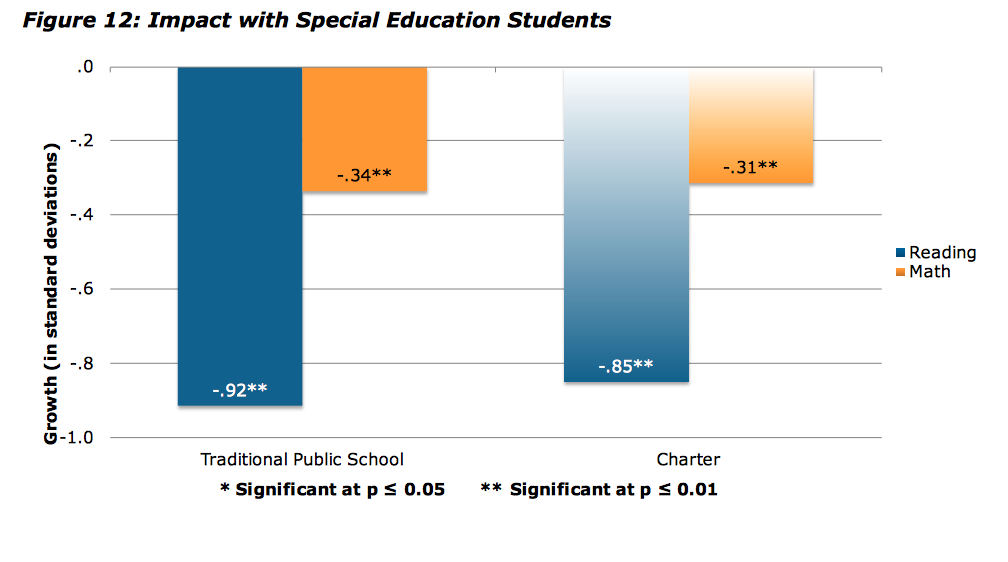

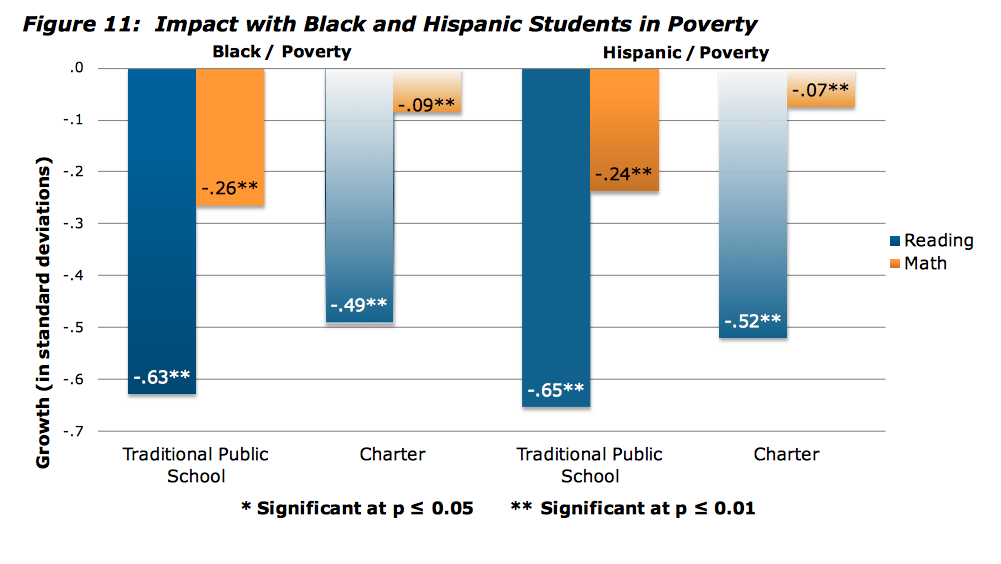

According to a Brookings study, charters in low-income and high-minority urban areas “have large, positive effects on educational outcomes” that are better than in district schools, and those effects are “particularly large for disadvantaged [and] SPED students” (see figures 1-3).[20] Another recent study showed that Boston charters that opened new schools after the cap was raised in 2010 “were able to maintain their strong results.”[21] On the other hand, students in rural and suburban charters “do the same or worse” than students in district schools.[22] The charter cap does not currently affect expansion of schools in suburban and rural areas, as they have not reached the cap.

The pro-charter side’s argument centered on ensuring that all students have access to a quality education. They argued that the referendum would modestly increase charters, and one ad even ended with “Yes on 2: for stronger public schools.”[23] Boston Mayor Marty Walsh, a traditional charter supporter and former member of the board of a Boston charter,[24] opposed the ballot question due to the “pace and scope” of charters that the referendum would allow for. He called the referendum “a looming death spiral aimed squarely at the most vulnerable children in our city.”[25] Sweeney, the Boston finance chief, agreed and thought that 12 new charters per year could “nearly eliminate the Boston Public Schools.”[26] If only 3 new charters were approved each year in Boston over the next decade, the Boston funds going to charters would increase from 5 to 20 percent. Charter advocates responded by saying that Boston has to “be responsible for getting its own fiscal house in order,” and that the city will have to close schools.[27] Nonpartisan city officials and financial watchdogs agreed with the No on 2’s argument that the increase in charters would drain dangerous amounts of money from public schools.

In Lowell, the cost of charters rose by 8.6 million over the past 9 years, but the state funding has stayed flat. Disproving another central Yes on 2 argument, “the charter school waitlist in Lowell…is dwarfed by the number of kids waiting to get into district schools.”[29] Lowell ended up voting against charters by 56.8 to 43.2.[30] The No side’s arguments spread far beyond education advocates to reach the average voter.

The No campaign “successfully connected charter school expansion to dark money and to a market-based ideological agenda,” revealing the Wall Street businessmen, conservatives, and New Yorkers that they argued were pouring money to dictate what’s best for Massachusetts. Since 2010, cities such as Boston, Fall River, and Lawrence have had an increase of 83% in charter spending but only 15% increase in state education aid. This results in money taken from other portions of the city budget, and the cities affected already have some of the highest poverty rates in the Commonwealth.[31] Due to overhead costs such as building maintenance and transportation, schools may “not be able to adjust to the loss of revenue” to charters.[32] Moody’s Investors Service agreed that passage of question 2 would be “credit negative” for the cities of Boston, Springfield, Lawrence, and Fall River.[33] The yes campaign responded by denying these concerns, stating that charters have “zero impact on district school finances.”[34] After question 2’s failure, Moody’s said that that result is “credit positive” for MA cities.[35]

The Yes side’s financial dominance allowed it to air an unprecedented amount of ads for a ballot campaign. One frequently aired ad consisted of Governor Baker saying, “Imagine if your kid was trapped in a failing school,” reaching for the emotions of white suburban voters to do what’s right for Black and Latino children in inner cities, whose images flash across the screen. Another ad said that it’s critical to raise the cap in order to remove what it claimed to be 37,000 students off charter waiting lists in MA. Great Schools MA’s TV ads “contain several themes from the pro-charter playbook,” and therefore the failure of this messaging means that it can also fail in future campaigns. For instance, the Boston Globe op-ed supporting question 2 emphasized students “languishing on waitlists.”[36] Good aspects of the traditional system “were generally portrayed as exceptions in a failing system,” which is false in Massachusetts’s top in the nation system. Since MA students rank first in the nation, voters are likely to oppose any drastic changes to the current system; the No campaign’s portrayal of the Yes side as extremist led many traditionally pro-charter politicians to take what they perceived to be the safer option and oppose question 2, thus shifting public opinion.

The most senior education officials in America backed the pro-charter narrative, with Secretary of Education John King, Arne Duncan, as well as Congressman Stephen Lynch, and Speaker DeLeo in MA. They joined together to attempt to unite the Democrats in an ad titled “Real Democrats are YES on Question 2.”[37] The No side included many politicians and officials who had traditionally been pro-charter. Mayor Walsh’s opposition to question 2 sent a clear message that opposing drastic expansion of charters does not mean one has to oppose charters themselves. Walsh opposed question 2 due to the deep budgetary implications it would have on Boston Public Schools. Mobilizing pro-charter politicians to oppose question 2 by depicting it as radical was a critical strategy; “more charter supporters recognize that Question 2 is the wrong solution” due to the dramatic increase of charters allowed as well as the lack of local control.[38]

In 2015, 412 million was taken from the 243 school districts and given to charters.[39] The No campaign successfully encouraged conversations with friends and neighbors about how much will be lost to charters if the number of charters dramatically increases. They emphasized the fact that 12 new charters per year would in 10 years nearly triple the number of MA charters. Furthermore, the dropping of the limit on the amount that a district could lose to charters could effectively eliminate public education in certain cities.[40]

A Skewed Budget: Financial Aspects of the Referendum Campaign

The Yes side spent $23.6 million to the No side’s $14.1 million,[41] making it the most expensive referendum campaign in MA history. The top 5 yes campaign donors were FES, followed by Alice Walton, the group Strong Economy for Growth, Jim Walton, and Michael Bloomberg. In contrast, the no campaign’s top donors were MTA, NEA, AFT, and AFL-CIO.[42] Local teacher unions in cities and towns affected by charters, such as Boston, Lowell, and Lawrence, also donated thousands.[43] Massachusetts corporations MassMutual Financial, State Street Bank, EMC Corporation, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals all contributed to Great Schools MA.[44] Wealthy out-of-state donors also poured money into the pro-charter effort; Arkansas residents and Walmart heirs Alice and Jim Walton donated $1.8 million while Michael Bloomberg gave $490,000.[45] FES poured 17 million to the Yes campaign but is not required to disclose donors and is registered in New York.[46] For “average voters…the outsized role being played by rich New Yorkers was utterly incomprehensible.”[47] $778,000 was also donated by bankers that manage MA pension funds to question 2.[48] The No campaign successfully crafted a narrative that conveyed the fact that wealthy, white out-of-state donors thought they knew what type of education was best for Massachusetts’ inner-city children. New England NAACP president and No on 2 campaign chair Juan Cofield said that “this is a truly unprecedented financial push by the charter industry to buy our election with untraceable money.”[49] The MA Charter Public School Association said that the out-of-state money from financial executives is essential to combating the financial power of teacher unions, despite the fact that the No side had nearly half the money of the Yes campaign.

The well-funded campaigns produced many TV ads and direct mail, which resulted in many more voters paying attention and thus more likely to make an informed choice. Opposition to charters became more than a niche issue. Undecided voters realized that there was “something fishy” about the Yes on 2 campaign’s seemingly constant back-to-back TV ads. This suspicion was confounded by additional deceptive tactics; for instance, one of the five pro-charter campaign committees was called, “Advancing Obama’s Legacy on Charter Schools Ballot Committee,” tying the yes campaign to Obama despite the fact that he did not weigh in on either side.[50]

Leading the Opposition: The Role of Teacher Unions in the Campaign

For the past few decades, teacher unions had been on the defensive about charters. But throughout the campaign, unions–particularly the MTA under Barbara Madeloni–were on the offensive. It was reported that $778,000 was donated to Great Schools MA by “executives from eight financial firms that hold management contracts with the state pension fund,” which is led by strong charter-supporter and popular Republican Governor Charlie Baker.[51] MTA and AFT-MA filed with the SEC to call for federal and state investigation into hedge fund managers’ donations to the yes campaign. Those executives cannot donate to Baker’s campaign due to campaign finance regulations, but they are able to donate to the pro-charter campaign and thus gain favor with him. Campaign finance experts said that this is a way for executives to “legally circumvent pay-to-play rules.”[52] Madeloni was on offense in a statement, saying, “it is appalling that ads starring [Baker] are being financed by donations from Wall Street fund managers who have an interest in currying favor with the administration.”[53] Baker called it a “distraction.”[54] While the investigation did not go anywhere, it obtained negative media coverage for the pro-charter campaign and contributed to the public perception of the Yes side being funded by wealthy donors disconnected from Massachusetts communities.

NEA President Lily Garcia said, “This is really important for us.” NEA’s 3 million members make it the largest union in America, and thus its backing carries substantial weight. Politico wrote before the election that the failure of question 2 would be “a significant symbolic coup for teachers unions.”[55] Failure of question 2 would also “deter other states from considering [charter] expansions amid signs the anti-charter side is gaining momentum.” The union’s first victory came in the form of the Democratic Party platform at the 2016 convention, which, at the personal request from AFT President Randi Weingarten, was amended to be more anti-charter than ever.[56] The grassroots no on 2 campaign was driven by local teacher unions, which are present in every district and are run and staffed almost entirely by teachers in that district. For instance, Belmont Education Association (BEA) handed out anti-charter flyers containing the BEA logo at major Belmont events. Parents’ “conversation with local teachers played a central role in building opposition.” One voter said that teachers in her town of Brookline “are the ones who really made up my mind.”[57] A variety of other unions, from AFSCME to CWA, joined the teacher unions to form a broad labor coalition under the SOPS umbrella, expanding the grassroots reach of the anti-charter effort.

The pro-charter side claimed that teachers were pressured by the union to oppose question 2. One teacher said that on the first day of her job, all teachers met in the auditorium. The local union president then gave a speech about the No campaign, and slips of paper were passed out to sign up for the No campaign.[58] Others argue that it’s a “lazy script” to simply attribute defeat of question 2 to teacher unions. In reality, “the vote…represents a political realignment” on the charter issue due to progressives firmly united against them.[59] People on the ground understood this, though those out-of-state were disconnected and thus “stunned when Elizabeth Warren announced she was No on 2,” failing to understand the degree of the realignment.

From the Bottom Up: Grassroots Organizing and the Leadup to the Question 2 Vote

Save Our Public Schools (SOPS) was the No campaign’s umbrella organization, which itself is a more direct branding than the vague name Great Schools MA. Organizations under the umbrella included MA Teachers Association, AFT Massachusetts, New England NAACP, Citizens for Public Schools, MA AFL-CIO, and other community groups.[60] The role of unions as running the No campaign, a narrative promulgated by the Yes campaign and mainstream media, is “exaggerated.” Teacher unions “were only one component of a broad-based and diverse No coalition.” Unpaid volunteers “did a staggering amount of work.” For instance, parents in Boston alone were organized into the group Quality Education for Every Student, which ran “highly organized” canvasses and phone banks consistently throughout the summer and through election day.[61] Anti-charter volunteers contacted 378,000 households in Boston while the Yes campaign contacted 150,000 in Greater Boston.[62] Average people took it upon themselves to help out the No campaign; for instance, parents made videos that went viral on social media, and volunteers “turned their homes into makeshift call centers” to phone bank. Many students also contributed by canvassing, phone banking, and using the infrastructure built during their 2016 budget walkout.[63] “The coalition extended well beyond teacher unions”[64] to include civil rights groups and social justice organizations. All of these groups “fanned out across the state every weekend” to spread the word. The No campaign canvassed 1.5 million voters–a stunning figure for a referendum campaign–and the final tally was 2 million votes against the measure. Therefore grassroots campaigning truly did make a large difference, and the victory indicates “the potential of substantial pushback against the corporate agenda from coordinated grassroots organizing.”[65]

The Yes campaign had far fewer people canvassing, phone banking, and spreading the word via social media.[66] Their “grassroots” field operation was actually made up almost entirely of people who were paid to knock doors, make phone calls, hold signs, and poll watch. Many were not even from MA. The campaign attempted to portray an image of being driven by support from low-income, inner-city people of color. A few parents of color, whose children went to Boston charter schools, spoke at highly choreographed Yes on 2 rallies to portray an image of African-American support. In the end, it was impossible to create support where it didn’t exist. The rallies and support for the No on 2 campaign were less scripted and more genuine.

215 School Committees passed resolutions opposing question 2, highlighting the loss of funds to their district schools and thus reinforcing the No campaign’s central argument. They also emphasized the lack of ELL and SPED resources in charters, which leave district schools to take on the burden of financing those more expensive students. Because the resolutions were passed consistently from the spring through the November election, they provided the No campaign with a “strong sense of momentum” that was publicized in order to control the media narrative.[67] Each local school board resolution resulted in media coverage in each city and town, and allowed local canvassers and phone bankers to gain traction. Use of school boards could be an impactful strategy in the success of future campaigns.

Racial Aspects and the African-American Mobilization Against Question 2

Black and Latino parents organized in their communities through groups such as the NAACP, Black Educators Alliance of MA, and Union of Minority Neighborhoods.[68] NAACP not only endorsed No on 2 but was a direct member of the campaign committee, and Juan Cofield–NAACP New England President and SOPS chair–was the public face of the No campaign. This was critical not only in turning a substantial constituency against charters, but also in showing that the Yes campaign’s narrative of voting yes to support inner-cities is backward because inner-city voters overwhelmingly opposed question 2. A few months before the vote, the NAACP convention voted for a moratorium on charters expansion “until they adopt the same level of oversight, civil rights protections, and transparency as public schools.”[69]

Some black pro-charter organizations opposed the NAACP position, such as the Black Alliance for Educational Options and African-American Boston newspaper Bay State Banner.[70] The Yes campaign used tactics with underlying racial motives; for instance, they sent a mailing covered by a picture of President Obama, with text that said “preserve Obama’s education legacy,” yet Obama was never involved in either side. FES created a group called Unify Boston, which spent months getting signatures from parents of color who wanted “great neighborhood schools.” Yet when the leaders told the signature gatherers “that the actual goal of the campaign was to lift the charter cap, a revolt broke out.” A former organizer remarked, “It’s like they think people of color are stupid.”[71]

Black politicians such as Boston City Councilor Tito Jackson and Boston NAACP President Michael Curry played a prominent role in mobilizing their community against question 2. Both represented the No side in debates, attended rallies, and served as “go-to persons for Boston newspaper articles on the campaign.”[72] They showed the depth of No campaign’s support in the black community, rather than the artificial image of support that the Yes campaign attempted to portray.

In areas of Boston like Mattapan, with some of “the lowest performing schools in the state, opposition to Question 2 ran deep,”[73] with many people repulsed by outsiders believing they knew best without actually being on the ground in the community. Boston NAACP president Michael Curry said that “communities of color spoke loudly.”[74] Some of the most emphasized pro-charter arguments highlighted the need to support students of color in failing schools. For instance, one journalist wrote a piece titled, “It’s Heartbreaking’: Boston Parents Ask Why Their Wealthy Neighbors Are Fighting Charter Schools.”[75] This piece tried to portray charters as supported by people of color who live in areas with the highest concentration of charters. But the overwhelming 2 to 1 opposition in those areas showed the opposite; the landslide against charters in inner-city Boston is even a larger margin than the statewide result.[76] Civil rights leaders “say families of color yearn for something deeper [than charters]: A plan to improve the quality of education…so they don’t need alternatives.”[77]

A New Era: Democratic Party Solidarity Against Question 2

Democrats and Republicans initially supported question 2 in similar numbers.[78] In the final vote, Democrats opposed it overwhelmingly. At the June 4th, 2016 MA Democratic State Convention, an event I attended, “Save Our Public Schools” signs abounded despite the fact that the question had not yet even been certified for the ballot. Signatures were submitted by the pro-charter campaign on June 22nd, and the question was certified on July 6th.[79] Pro-charter forces also made a massive push for Democratic delegates and activists. DFER, for instance, was the only outside group to send an official mailing to delegates prior to the state convention. That mailing was an invitation to a DFER breakfast for delegates, which had elaborate food and was attended by pro-charter state legislators. SOPS did not have a breakfast, but it was clear at the convention that they had the people. Numerous SOPS tables appeared throughout the convention hall, and anti-charter stickers were a near-constant sight on delegates while hardly any pro-charter stickers could be spotted. DFER also paid for multiple breakfasts–which cost around $5000 each–at the Democratic National Convention,[80] attempting to portray an image of support for charters in MA.

The No on 2 campaign “tapped into genuinely viral energy.” This spurred the MA Democratic Party to officially oppose question 2, which likely would not have happened without the enormous grassroots mobilization. This stance against charters is at odds with some Democratic legislators, including Speaker DeLeo.[81] Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren both endorsed the anti-charter campaign. Warren echoed the central argument of the anti-charter campaign, saying that more charters would damage the education of “students in districts with tight budgets where every dime matters.” She emphasized that 400 million was taken from public schools to charters, resulting in cuts to district schools including “in arts, technology, AP classes, preschool, bus service, and more.”[82] In a blue state like MA, Democratic unity contributed greatly to the No campaign’s landslide victory.

Crossing the Partisan Divide to Oppose Charters: Geographic Trends in the Election Results

The anti-charter effort was victorious in almost every town in Massachusetts. The few towns that voted yes were also some of the wealthiest in Massachusetts. Weston, easily the wealthiest town with median household income of $201,200,[83] voted 60-40 in support of charter schools, the second highest margin in the state (the highest was 61-39 in Aquinnah, a tiny affluent community on Martha’s Vineyard).[84] Dover, the second wealthiest town, voted 58.7 to 41.3 for charters, the third highest pro-charter margin in the state. Sherborn, with the fifth highest pro-charter margin, is also the fifth wealthiest town. There is a clear correlation between the wealthiest towns and the highest pro-charter margins. The exclusive affluent communities of Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard supported charters. On Martha’s Vineyard, wealthy white Edgartown and Chilmark voted yes, while the heavily African-American community of Oak Bluffs voted no, signaling that pro-charter support among the wealthiest Bay Staters was limited to whites.

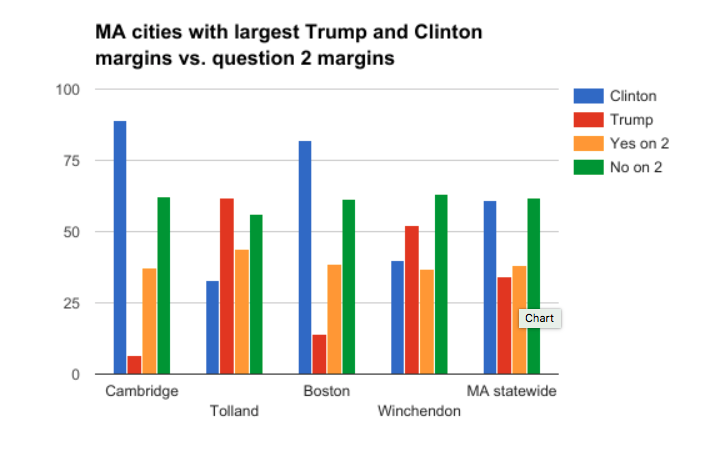

Towns that voted for Trump by high margins also voted against charters by margins similar to those in Boston, Worcester, and other liberal cities. For instance, Tolland had the highest margin for Trump and Cambridge had the highest margin for Clinton, but their charter margin was remarkably similar. This implies that Trump-DeVos education policies are not popular with his white working class base, and therefore it’s critical for public education advocates to mobilize that group in order to most effectively resist. The No campaign’s tactic of grassroots outreach in all areas of the Commonwealth succeeded even in white, working-class, Trump supporting areas and therefore a similar anti-charter strategy can be successfully applied across the Midwest and throughout the country. The statewide trend was replicated along wealth lines in Boston itself. The largest anti-charter margin occurred in the predominantly low-income and African-American area of Roxbury while the highest margin in support of charters occurred in the wealthy and white Back Bay.[85] The coalescence of the black community around the anti-charter campaign was reflected in the inner city vote total, with Roxbury, Mattapan, and Dorchester all voting around two to one against question 2. All cities and towns with a large number of charter schools voted against question 2. In fact, no town that voted for charters has a single charter school.

A Model for the Nation: Applying Lessons from the Massachusetts Anti-Charter Campaign to Future Public Education Advocacy

The day after the vote, the Boston Globe headline read, “Crushing defeat leaves charter-school movement in limbo.”[86] This “exceeded the worst case scenario” of charter supporters. One researcher at a pro-charter thinktank acknowledged that the anti-charter side came out ahead on every argument.[87] The No side gained the upper hand because it convinced undecided voters while the Yes side hardly expanded its base. DFER was “quick to issue statements of “we’ll be back – talking-pointed bravado…that conveyed nothing so much as a failure to recognize the magnitude of their loss.”[88] Charter advocates say not to read into the vote. But according to the National Education Policy Center, “the MA campaign suggests that the neoliberal, pro-charter narrative” is ending.[89]

MA’s vote against charters was immediately lauded nationwide as a major step in stopping the tide of charters.[90] Diane Ravitch noted that “this was the first contest over charter schools in which the key issues became public,” highlighting million-dollar donations from financial executives.[91] The Yes effort backfired by creating their worst nightmare, uniting progressives and Democrats against charter schools and into a powerful grassroots force that will continue to fight charters across MA; “all of the momentum is on the [anti-charter] side now.”[92]

Race was a critical aspect. Importantly, the “strong and visible black support for the No campaign upended the Obama-era consensus of broad, bipartisan support for charter schools.”[93] The MTA was the lead organizer in creating the No campaign and its successful strategy. MTA President Madeloni’s decision to pull all the stops on the anti-charter campaign was controversial even within the MTA itself. But her decision to go all-out arguably made all the difference. Teachers and their local unions powered much of this campaign, leading canvasses door to door in every area of the Commonwealth. Teacher unions now have more leverage and will take a broader role against charters in the Trump era.

The landslide victory against charters, and the campaign that made it happen, was unprecedented and lays the path for future resistance to charters. The same tactics and messaging, from coalescing support from the black community to organizing on a grassroots level, can be used not just on other charter school ballot campaigns but also on resisting charters at the legislative level and in other capacities. In the Trump-DeVos era, the No on 2 campaign’s success forms the blueprint for resistance to the privatization of public education.

1. Rinaldi, Jessica. “How Many Charter Schools Are Too Many? – The Boston Globe.” BostonGlobe.com. 03 Nov. 2016. Web. 28 Apr. 2017.

2. Mass. Democrats Vote To Oppose Charter School Question. (n.d.). Retrieved May 03, 2017.

3. Blum, L. What we can learn from the Massachusetts ballot question campaign on charter school expansion. National Education Policy Center.

4. Schoenberg, S. S. (2016, November 15). Moody’s: Vote against charter school expansion ‘credit positive’ for Massachusetts cities like Springfield.

5. Cohodes, S., & Dynarski, S. M. (2017, March 29). Massachusetts charter cap holds back disadvantaged students | Brookings Institution. Retrieved May 03, 2017.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. Jennifer Berkshire. “What Went Down in Massachusetts – Have You Heard.” Have You Heard. Web. 28 Apr. 2017.

10. Blum, L. What we can learn from the Massachusetts ballot question campaign on charter school expansion. National Education Policy Center.

11. Jennifer Berkshire. “What Went Down in Massachusetts – Have You Heard.” Have You Heard. Web. 28 Apr. 2017.

12. Blum, L. What we can learn from the Massachusetts ballot question campaign on charter school expansion. National Education Policy Center.

13. Jennifer Berkshire. “What Went Down in Massachusetts – Have You Heard.” Have You Heard. Web. 28 Apr. 2017.

14. Davis, J. (2016, November 10). Crushing defeat leaves charter-school movement in limbo – The Boston Globe.

15. Blum, L. What we can learn from the Massachusetts ballot question campaign on charter school expansion. National Education Policy Center.

16. Ibid.

17. Ibid.

18. Why Question 2 grassroots opposition is growing. (2016, August 29). Retrieved April 28, 2017.

19. Ibid.

20. Cohodes, S., & Dynarski, S. M. (2017, March 29). Massachusetts charter cap holds back disadvantaged students | Brookings Institution. Retrieved May 03, 2017.

21. Rinaldi, Jessica. “How Many Charter Schools Are Too Many? – The Boston Globe.” BostonGlobe.com. 03 Nov. 2016. Web. 28 Apr. 2017.

22. Cohodes, S., & Dynarski, S. M. (2017, March 29). Massachusetts charter cap holds back disadvantaged students | Brookings Institution. Retrieved May 03, 2017.

23. Why Question 2 grassroots opposition is growing. (2016, August 29). Retrieved April 28, 2017.

24. Ibid.

25. Rinaldi, Jessica. “How Many Charter Schools Are Too Many?” The Boston Globe. BostonGlobe.com. 03 Nov. 2016.

26. Ibid.

27. Ibid.

28. Ibid.

29. Jennifer Berkshire. “What Went Down in Massachusetts – Have You Heard.” Have You Heard. Web. 28 Apr. 2017.

30. “Massachusetts Question 2 – Expand Charter Schools – Results: Rejected.” The New York Times. The New York Times. Web. 03 May 2017.

31. Schoenberg, S. S. (2016, November 15). Moody’s: Vote against charter school expansion ‘credit positive’ for Massachusetts cities like Springfield.

32. Ibid.

33. Staff, G. (2016, November 02). Charter school vote may hurt credit ratings, Moody’s warns Boston, 3 other cities – The Boston Globe.

34. Ibid.

35. Schoenberg, S. S. (2016, November 15). Moody’s: Vote against charter school expansion ‘credit positive’ for Massachusetts cities like Springfield.

36. Blum, L. What we can learn from the Massachusetts ballot question campaign on charter school expansion. National Education Policy Center.

37. Hefling, K. (2016, November 04). Democrats feud over charter schools in Massachusetts. Retrieved May 03, 2017.

38. Why Question 2 grassroots opposition is growing. (2016, August 29). Retrieved April 28, 2017.

39. Ibid.

40. Ibid.

41. Shira Schoenberg. “Who Is Funding Massachusetts Question 2, on Charter School Expansion?” Masslive.com. 05 Nov. 2016.

42. Massachusetts Authorization of Additional Charter Schools and Charter School Expansion, Question 2 (2016).

43. Shira Schoenberg. “Moody’s: Vote against Charter School Expansion ‘credit Positive’ for Massachusetts Cities like Springfield.” Masslive.com. 15 Nov. 2016. Web. 28 Apr. 2017.

44. Shira Schoenberg. “Who Is Funding Massachusetts Question 2, on Charter School Expansion?” Masslive.com. 05 Nov. 2016.

45. Ibid.

46. Shira Schoenberg. “Moody’s: Vote against Charter School Expansion ‘credit Positive’ for Massachusetts Cities like Springfield.” Masslive.com. 15 Nov. 2016. Web. 28 Apr. 2017.

47. Jennifer Berkshire. “What Went Down in Massachusetts – Have You Heard.” Have You Heard. Web. 28 Apr. 2017.

48. Shira Schoenberg. “Moody’s: Vote against Charter School Expansion ‘credit Positive’ for Massachusetts Cities like Springfield.” Masslive.com. 15 Nov. 2016. Web. 28 Apr. 2017.

49. Ibid.

50. Massachusetts Authorization of Additional Charter Schools and Charter School Expansion, Question 2 (2016).

51. Schoenberg, S. S. (2016, November 01). Teachers unions file complaint over ‘pay-to-play’ allegations involving charter school supporters.

52. Ibid.

53. Ibid.

54. Ibid.

55. Hefling, K. (2016, November 04). Democrats feud over charter schools in Massachusetts. Retrieved May 03, 2017.

56. Ibid.

57. Ryan, D. L. (2016, October 18). On charter schools, a new partisan divide – The Boston Globe. Retrieved May 03, 2017.

58. Crookston, Paul. “Massachusetts Teachers Pressured by Union Leaders to Oppose Charter Schools.” National Review. 07 Nov. 2016.

59. Jennifer Berkshire. “What Went Down in Massachusetts – Have You Heard.” Have You Heard. Web. 28 Apr. 2017.

60. Blum, L. What we can learn from the Massachusetts ballot question campaign on charter school expansion. National Education Policy Center.

61. Ibid.

62. Vaznis, James. “In Boston, Charter Vote Reflected Racial Divide – The Boston Globe.” BostonGlobe.com. 14 Nov. 2016. Web. 28 Apr. 2017.

63. Blum, L. What we can learn from the Massachusetts ballot question campaign on charter school expansion. National Education Policy Center.

64. Jennifer Berkshire. “What Went Down in Massachusetts – Have You Heard.” Have You Heard. Web. 28 Apr. 2017.

65. Blum, L. What we can learn from the Massachusetts ballot question campaign on charter school expansion. National Education Policy Center.

66. Ibid.

67. Ibid.

68. Ibid.

69. Strauss, V. (2016, October 15). NAACP ratifies controversial resolution for a moratorium on charter schools.

70. Blum, L. What we can learn from the Massachusetts ballot question campaign on charter school expansion. National Education Policy Center.

71. Jennifer Berkshire. “What Went Down in Massachusetts – Have You Heard.” Have You Heard. Web. 28 Apr. 2017.

72. Blum, L. What we can learn from the Massachusetts ballot question campaign on charter school expansion. National Education Policy Center.

73. Vaznis, James. “In Boston, Charter Vote Reflected Racial Divide – The Boston Globe.” BostonGlobe.com. 14 Nov. 2016. Web. 28 Apr. 2017.

74. Ibid.

75. Jennifer Berkshire. “What Went Down in Massachusetts – Have You Heard.” Have You Heard. Web. 28 Apr. 2017.

76. Vaznis, James. “In Boston, Charter Vote Reflected Racial Divide – The Boston Globe.” BostonGlobe.com. 14 Nov. 2016. Web. 28 Apr. 2017.

77. Ibid.

78. Ryan, D. L. (2016, October 18). On charter schools, a new partisan divide – The Boston Globe. Retrieved May 03, 2017.

79. “Massachusetts Authorization of Additional Charter Schools and Charter School Expansion, Question 2 (2016).” Ballotpedia. Web. 02 May 2017.

80. Mass. Democrats Vote To Oppose Charter School Question. (n.d.). Retrieved May 03, 2017.

81. Ibid.

82. Hefling, K. (2016, November 04). Democrats feud over charter schools in Massachusetts. Retrieved May 03, 2017.

83. Rocheleau, Matt. “A Town-by-town Look at Income in Massachusetts – The Boston Globe.” BostonGlobe.com. 18 Dec. 2015. Web. 03 May 2017.

84. “Massachusetts Question 2 – Expand Charter Schools – Results: Rejected.” The New York Times. The New York Times. Web. 03 May 2017.

85. Vaznis, James. “In Boston, Charter Vote Reflected Racial Divide – The Boston Globe.” BostonGlobe.com. 14 Nov. 2016. Web. 28 Apr. 2017.

86. Davis, J. (2016, November 10). Crushing defeat leaves charter-school movement in limbo – The Boston Globe.

87. Ibid.

88. Jennifer Berkshire. “What Went Down in Massachusetts – Have You Heard.” Have You Heard. Web. 28 Apr. 2017.

89. Blum, L. What we can learn from the Massachusetts ballot question campaign on charter school expansion. National Education Policy Center.

90. Education Victories Democrats Can Rally Around. (2016, November 10).

91. Good News on a Gloomy Night: Question 2 in Massachusetts Fails Overwhelmingly. (2016, November 09).

92. Jennifer Berkshire. “What Went Down in Massachusetts – Have You Heard.” Have You Heard. Web. 28 Apr. 2017.

93. Blum, L. What we can learn from the Massachusetts ballot question campaign on charter school expansion. National Education Policy Center.

Works Cited

Vaznis, J. (2016, November 14). In Boston, charter vote reflected racial divide – The Boston Globe. Retrieved April 28, 2017, from https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2016/11/13/boston-charter-vote-reflected-racial-divide/t5EI29okErZ7JDItnkPZKI/story.html

Blum, L. What we can learn from the Massachusetts ballot question campaign on charter school expansion. National Education Policy Center.

What Went Down in Massachusetts – Have You Heard. Retrieved April 28, 2017, from http://haveyouheardblog.com/what-went-down-in-massachusetts/

Cohodes, S., & Dynarski, S. M. (2017, March 29). Massachusetts charter cap holds back disadvantaged students | Brookings Institution. Retrieved April 28, 2017, from https://www.brookings.edu/research/massachusetts-charter-cap-holds-back-disadvantaged-students/

Cohodes, S., & Dynarski, S. M. (2017, March 29). Massachusetts charter cap holds back disadvantaged students | Brookings Institution. Retrieved May 03, 2017, from https://www.brookings.edu/research/massachusetts-charter-cap-holds-back-disadvantaged-students/

Crookston, P. (2016, November 07). Massachusetts Teachers Pressured by Union Leaders to Oppose Charter Schools. Retrieved April 28, 2017, from http://www.nationalreview.com/corner/441886/massachusetts-teachers-union-pressures-members-vote-against-charter-schools

Dark Money: Pro-Charter-School Fat Cats Took A Page From Offshore Gambling Tycoons. (n.d.). Retrieved April 28, 2017, from http://blogs.wgbh.org/masspoliticsprofs/2017/2/16/dark-money-pro-charter-school-fat-cats-took-page-offshore-gambling-tycoons/

Davis, J. (2016, November 10). Crushing defeat leaves charter-school movement in limbo – The Boston Globe. Retrieved May 03, 2017, from https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2016/11/09/crushing-defeat-leaves-charter-school-movement-limbo/Lj1JIwnZQIeTOD7sV6G5YL/story.html

Education Victories Democrats Can Rally Around. (2016, November 10). Retrieved April 28, 2017, from http://educationopportunitynetwork.org/education-victories-democrats-can-rally-around/

GOP Senate Leader from Suburbs Wants More Charters for New York City. (2017, April 24). Retrieved April 28, 2017, from https://dianeravitch.net/2017/04/24/gop-senate-leader-from-suburbs-wants-more-charters-for-new-york-city/

Good News on a Gloomy Night: Question 2 in Massachusetts Fails Overwhelmingly. (2016, November 09). Retrieved May 03, 2017, from https://dianeravitch.net/2016/11/09/good-news-on-a-gloomy-night-question-2-in-massachusetts-fails-overwhelmingly/

Hefling, K. (2016, November 04). Democrats feud over charter schools in Massachusetts. Retrieved May 03, 2017, from http://www.politico.com/story/2016/11/democrats-divided-on-mass-charter-school-expansion-230888

Mass. Democrats Vote To Oppose Charter School Question. (n.d.). Retrieved May 03, 2017, from http://www.wbur.org/edify/2016/08/17/mass-democrats-charter-school

Massachusetts Authorization of Additional Charter Schools and Charter School Expansion, Question 2 (2016). (n.d.). Retrieved May 02, 2017, from https://ballotpedia.org/Massachusetts_Authorization_of_Additional_Charter_Schools_and_Charter_School_Expansion,_Question_2_(2016)

Massachusetts Teachers Knock Out Corporate Charter School Scheme. (n.d.). Retrieved April 28, 2017, from http://www.labornotes.org/2016/11/massachusetts-teachers-knock-out-corporate-charter-school-scheme

“Massachusetts Question 2 – Expand Charter Schools – Results: Rejected.” The New York Times. The New York Times. Web. 03 May 2017.

Rinaldi, J. (2016, November 03). How many charter schools are too many? – The Boston Globe. Retrieved April 28, 2017, from https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2016/11/02/how-many-charter-schools-are-too-many/dU4TSVjIlfgNvnzHKj7M1I/story.html

Rocheleau, Matt. “A Town-by-town Look at Income in Massachusetts – The Boston Globe.” BostonGlobe.com. 18 Dec. 2015. Web. 03 May 2017.

Ryan, D. L. (2016, October 18). On charter schools, a new partisan divide – The Boston Globe. Retrieved May 03, 2017, from https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2016/10/18/charter-schools-new-partisan-divide/YQ3ZkMshShWkoVXZv4mR4N/story.html

Staff, G. (2016, November 02). Charter school vote may hurt credit ratings, Moody’s warns Boston, 3 other cities – The Boston Globe. Retrieved May 03, 2017, from https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2016/11/01/charter-school-vote-may-hurt-credit-ratings-moody-warns-boston-other-cities/bvEw1j0femPzR28M7mgTFN/story.html

Strauss, V. (2016, October 15). NAACP ratifies controversial resolution for a moratorium on charter schools. Retrieved April 28, 2017, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2016/10/15/naacp-ratifies-controversial-resolution-for-a-moratorium-on-charter-schools/?utm_term=.b8d575604ecf

Why Question 2 grassroots opposition is growing. (2016, August 29). Retrieved April 28, 2017, from https://commonwealthmagazine.org/education/why-question-2-grassroots-opposition-is-growing/

Schoenberg, S. S. (2016, November 15). Moody’s: Vote against charter school expansion ‘credit positive’ for Massachusetts cities like Springfield. Retrieved April 28, 2017, from http://www.masslive.com/politics/index.ssf/2016/11/moodys_no_vote_on_charter_scho.html

Schoenberg, S. S. (2016, November 01). Teachers unions file complaint over ‘pay-to-play’ allegations involving charter school supporters. Retrieved May 03, 2017, from http://www.masslive.com/politics/index.ssf/2016/11/teachers_unions_file_complaint.html

Schoenberg, S. S. (2016, November 05). Who is funding Massachusetts Question 2, on charter school expansion? Retrieved April 28, 2017, from http://www.masslive.com/politics/index.ssf/2016/11/who_is_funding_massachusetts_question_2_charter_schools.html