Introduction:

“The future is here; it’s just not evenly distributed.” That quote from a William Gibson science fiction novel is used widely in Silicon Valley to describe the technology landscape, but it applies to segregation as well. In the United States, schools are more segregated than they have ever have been despite the Brown v. Board of Education decision that outlawed separate schools for all races (Millhiser, 2015). In the U.S., over one-third of black and Latino students go to schools that are over 90% non-white, while more than one-third of white students go to schools that are over 90% white (Potter & Quick, 2016). The increase in segregation stems in large part from racialized housing practices such as redlining, blockbusting, and racial covenants that have led to the segregation of neighborhoods. These discriminatory practices prevented certain people from buying homes in better areas, which determined where people lived, and as a result, led to segregation in schools as well. Neighborhood stratification led to school segregation because school attendance zones were tethered to real estate and busing-based integration efforts have declined so more students go to the school closest to them (Potter & Quick, 2016).

I will focus primarily on the Sacramento, California district and how it has tried to address these discriminatory practices from the 1900s by instituting inclusionary housing policies to fight racial and economic segregation. Sacramento has succeeded, by and large, because it is considered one of the most diverse and integrated cities in the U.S. (Silver, 2015). Time magazine asked The Civil Rights Project to name the most residentially integrated city in the U.S., and they chose Sacramento (Orfield, 2016).

I will explain how housing discrimination caused segregation in neighborhoods and in schools and how Sacramento’s commitment to creating more affordable housing has had a positive effect in Sacramento on not only its neighborhoods but on the schools as well. By focusing on getting rid of neighborhood segregation, Sacramento has also succeeded in increasing the diversity in schools. In California, Sacramento has the most integrated large public school districts (Orfield, 2016).

While other research has examined how integrated Sacramento is as a city, this report is unique because it ties Sacramento’s focus on desegregating neighborhoods with desegregation in schools. Also, this report will examine the racial demographics in Sacramento public schools and the surrounding county in context with other cities to show how its diversity in neighborhoods is carrying over to the schools and how Sacramento can be an example.

Sacramento may turn out to be the future for school inclusion, once that future gets a bit more widely distributed.

Background

Housing Discrimination

Throughout the 1900s, the U.S. government, realtors, and banks conspired against minorities in a multitude of ways to prevent them from living in certain areas. One example of this is redlining, where banks disproportionately denied black people loans and mortgages so that they couldn’t afford to buy a home. Neighborhoods where black people lived were colored in red and were deemed ineligible for support for the Federal Housing Administration. An example of Chicago in 1939 where an entire area was considered to be minority housing is shown below. Blacks were denied services because of raising prices and because people wanted to maintain the current ethnic composition of the area that would be primarily white (Coates, 2014).

Another practice was blockbusting, where realtors would essentially encourage “white flight.” They would sell a home to a black person in an area and then encourage the white people in the area to move. The realtor would buy it from a white family for a relatively low price and then would charge much more than market rate when selling to a black person, because they may not have had any other options (Coates, 2014). The final discriminatory housing practice that I’ll mention (though there are many more), is racial covenants. This was a legal way to prevent blacks from living in an area, because neighborhoods could band together and prevent blacks from moving into the neighborhood by agreeing not ever sell their home to a black person. For example, by 1940 in Chicago and Los Angeles, 80% of properties had racial covenants (Fair Housing Center, 2010).

Neighborhood Segregation Effects

These methods to prevent blacks from living in white neighborhoods resulted in the segregation of neighborhoods that have had crippling effects for minorities in the U.S, such as increased poverty, poorer health, and higher exposure to violent crime (Bethea 2013). One of the main effects of neighborhood segregation is the segregation of schools. School districts lines tend to be drawn to reflect the neighborhoods and can be segregated by race, as transportation from one school district to another is costly and not time-efficient. Segregated schools tend to lead to better schools for white students and often impoverished schools that don’t have the same resources for minorities (Walsemann, 2010). There have also been shown to be many benefits of racially integrated schools such as obviously allowing minorities to get the same opportunities as white students but also to socialize students and prepare them for a diverse workforce where employers value people who can work with others from diverse cultural backgrounds (Stuart, 2016). In addition, a report found that, “researchers have documented that students’ exposure to other students who are different from themselves and the novel ideas and challenges that such exposure brings leads to improved cognitive skills, including critical thinking and problem solving.” To be sure, there are some drawbacks about promoting the integration of schools, such as the fact that the onus is often placed on minority students and their families to be the ones doing the integrating, and they often have to leave the comfort of their own schools to go to a new school with new people. But, promoting neighborhood integration means that minority students won’t have to travel a long ways to get to a quality school – instead, their neighborhood school will be diverse and likely of better quality.

History in Sacramento

Sacramento, California is one of the cities in the U.S. that is actively trying to address segregated neighborhoods by introducing an inclusionary housing policy. Sacramento passed the Mixed-Income Housing Ordinance in 2000 that applied to all residential developments over nine units in “new growth areas” (Brunick, 2004). The ordinance requires that 15% of all units by affordable housing. The goal is to fight racial and economic segregation by allowing mid-to-low income families to purchase homes in a multitude of areas.

This inclusionary housing policy in Sacramento has contributed to Sacramento becoming one of the most diverse and integrated cities in the U.S, and other large cities could follow their model (Silver, 2015). Sacramento was considered the third most diverse city in the U.S. from a citywide level, the most diverse city from a neighborhood level, and the second most diverse city from an integration standpoint, as shown in the graph below (Silver, 2015).

Inclusionary Housing in Sacramento

Sacramento decided to adopt an inclusionary housing ordinance in large part because of the affordable housing crisis and to counteract the legal discriminatory practices from the 1900s. In the late 1900s, house prices skyrocketed, as “the cost of a new home nearly tripled and the cost of an existing home nearly doubled” because of high demand for homes, scarcity of available land, and a low supply of houses (Padilla, 1995). The average sales prices of homes increased at a faster rate than the average family income did; from 1994-2003, the average family income increased by 44.6%, but the average sales price of a home increased by 101.5% (Basolo & Scally, 2008).

Sacramento adopted the Mixed-Income Housing Ordinance on October 3, 2000. The main aspect is that it required 15% of new housing projects to be affordable housing for lower-income families. Some other aspects of the ordinance are: it applies to residential projects of 10 or more dwellings, 5% must be low income units and 10% must be very low income unites, developments of 50% or more of inclusionary housing can’t be located next to one another, and the design of inclusionary units needs to be compatible with the other units (Sacramento City Council, 2015).

The idea behind inclusionary housing in Sacramento is that by having more mixed-income and diverse communities, lower-income workers can own a home near where their jobs are, and their kids can live near good, quality schools that have a history of performing well academically (Garvin, 2015). In this way, low-income families can afford houses in already very good neighborhoods, which will build equity over time.

The Need for Inclusionary Housing

The outright housing discrimination in the U.S.that led to neighborhood inequality was banned by the Fair Housing Act of 1968 that addressed issues of, for example, redlining, blockbusting, and forming racial covenants. It deemed these practices to be unconstitutional and tried to make sure the buyer or renter could get access to affordable housing (U.S. Department of Justice, 2015). While these practices were made illegal, the damage had been done, and neighborhoods have remained segregated since then. There have been very few policy efforts to address the segregation problem in the U.S., as “housing policy in the United States appears to be in a protracted, transformative period that combines a lack of strong federal leadership with continued reliance on increasingly uncertain federal funding” (Basolo and Scally, 2008). This may be the case because many politicians are uncomfortable talking about race and don’t want to acknowledge the rampant inequality in neighborhoods around the country.

As stated in a UCLA report on segregation in California, “Housing segregation is a root cause of school segregation. Any long-term policy to foster increased and lasting school integration must determine how to enforce fair housing and affordable housing policies more effectively” (Orfield, 2014).

Inclusionary Housing in Sacramento and its School Districts

We can see the benefits of inclusionary housing with the effects that it has had on the neighborhoods in Sacramento, because of how integrated Sacramento is as a city. Show below is a graph (using this tool) of the downtown Sacramento area, where each dot represents an ethnicity. A blue dot is white, a green dot is black, a red dot is asian, and an orange dot is hispanic. The darker the dot, the more concentrated a certain population is in that area. While there are certain areas that seem to be primarily one race, such as the red section in the middle, the city as a whole appears very diverse. In fact, Sacramento is the most integrated major city in the U.S. (Silver, 2015). It’s a city where every race is in the minority. Sacramento County is 12.7 percent Black, 13.5% Asian, 30.7% Hispanic, 32.4% White, and 10.3% other.

Data Analysis

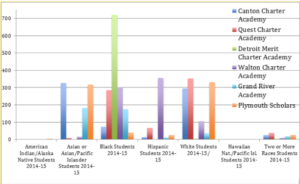

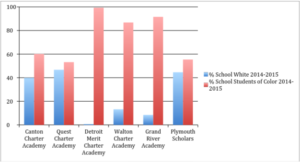

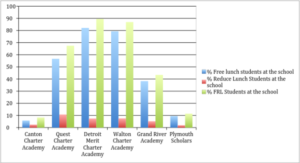

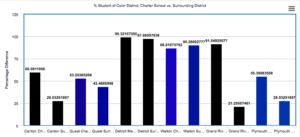

The desegregated neighborhoods have had the effect of making the Sacramento City Unified School District (SCUSD) one of the most diverse and desegregated in the U.S in terms of the wide range of students they serve (Rutherford, 2013). The SCUSD is made up of public schools in the area and serves 36.5% Hispanic students, 18.6% white students, 19.1% Asian students, 18% black students, and 5.3% multiracial students (Rutherford, 2013). These numbers show the wide range of students who attend public schools in Sacramento. The one caveat is that the Hispanic population is somewhat overrepresented in the public schools, and the white population is somewhat underrepresented, which is shown in the graphs below.

Even though there is a difference (15.9%) in the percentage of white students who attend the Sacramento public schools (18.6%) and the white percentage of the population (34.5), it is much smaller than in other major cities. This may be a result of Sacramento’s focus on a move toward integrating neighborhoods.

Below, I look at two other cities (Chicago and Baltimore) to show how the disparity between the percentage of white students in public schools versus the percentage of white people in the population in Sacramento is much less than these three cities that have fairly high levels of neighborhood segregation. The population numbers of Sacramento, Chicago, and Baltimore are from the 2010 U.S. Census.

Chicago:

As seen in the map, the neighborhoods in Chicago are very segregated. And, the percentage of white students who attend the public schools in Chicago is much less than the white makeup of the city as a whole. Shown below are two pie charts that show the difference (CPS).

This shows that the number of white students in Chicago (9.9%) is disproportionately low to the number of white people in Chicago (39%). The reason for the disparity in white students in the public schools may because because of the segregated nature of the neighborhoods and schools in Chicago.

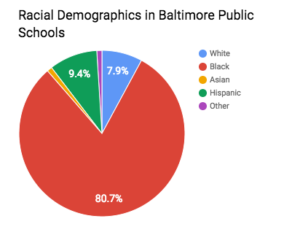

Baltimore:

Again, Baltimore is shown above to be a very segregated city. And, the number of white students in Baltimore (7.9%) is disproportionately low to the number of white people in Baltimore (962%).

This effect is also seen somewhat in Sacramento but to a much lesser extent, which shows that Sacramento may be on the right path with the inclusionary housing policy.

Benefits of Integration in Schools

In Sacramento, the fact that the neighborhoods and schools are very desegregated has positive effects for the school and for the students. Diversity in Sacramento schools has cognitive, social, and emotional benefits for students, because the students get a chance to interact with a multitude of people from a variety of backgrounds (Wells, 2016). Diversity in schools also has purported benefits in the workforce, as one study found that 96% of major employers say that it’s important for employees to be “comfortable working with colleagues, customers, and/or clients from diverse cultural backgrounds” (Wells, 2016). Diversity in schools allows students to interact with people of different backgrounds, which will help prepare them socially for the future.

Effects of Desegregation in Sacramento Schools

It is hard to know what exactly the benefits of integration have been so far, since the inclusionary housing policy has only been in place since 2000. But, there are still some signs that the Sacramento City School District is improving – student test scores moved up substantially on the state’s Academic Performance Index (API) from 2011-2012 (SCUSD, 2012). English Language Learners, in particular, has the greatest improvement as a demographic by moving up 15 points in API to above the state average for ELL students. These are just a couple example of improvements in Sacramento schools. It will be important to follow the progress in Sacramento over the next couple of decades to see how the schools fare academically and socially to see if the neighborhood effects of desegregation can carry over to the schools.

Conclusion

One potential solution for integrated neighborhoods is the inclusionary housing policies that have been voluntarily adopted more and more by cities in California. They are needed because of the rising housing costs in the U.S. that are making it harder for impoverished families to buy good houses in good areas. The main purported benefit of inclusionary housing policies has been to make neighborhoods more diverse both economically and racially (Basolo & Scally, 2010). To be sure, there have also been potential negative effects of inclusionary housing such as the supply of homes may go down because the developers may lose incentive to build and construction activity would be reduced and then affordable houses wouldn’t be built. But, there has been no empirical data to show that this is the case.

Overall, inclusionary housing policies in Sacramento have had the effect of making Sacramento one of the most integrated cities in the U.S. The change has been recent, so it is hard to know for certain whether or not the effect will carry over fully to schools. But, there has been some positive changes in the Sacramento school district schools that signifies that focusing on housing policies may be the solution.

The inclusionary housing model has been successful in Sacramento and can be expanded and applied to many more large cities around the U.S. We need more people to be aware of the segregation problem in neighborhoods and in schools in order to fix the rampant problem. With awareness comes more ideas for solutions, and we can start with inclusionary housing practices. By looking at the example in Sacramento, we can make this desegregated and integrated future real everywhere across the United States.

Works Cited

Basolo, V., & Scally C. (2008). State innovations in affordable housing policy: Lessons from California and New Jersey, Housing Policy Debate, 19:4, 741-774

Bethea, B. J. (2013, November 6). Effects of segregation negatively impact health | The Source | Washington University in St. Louis. Retrieved May 03, 2017, from https://source.wustl.edu/2013/11/effects-of-segregation-negatively-impact-health/

Brunick, N. (2004). Inclusionary Housing: Proven Success in Large Cities. Zoning Practice: American Planning Association, (10).

City Schools at a Glance. (n.d.). Retrieved May 03, 2017, from http://www.baltimorecityschools.org/about/by_the_numbers

Coates, T. (2014, June). The Case for Reparations. Retrieved May 03, 2017, from https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/

CPS Stats and Facts . (n.d.). Retrieved May 03, 2017, from http://cps.edu/About_CPS/At-a-glance/Pages/Stats_and_facts.aspx

Garvin, C. (2015, July 23). ‘Segregation’ will happen if the city of Sacramento ditches inclusionary housing – Bites – Opinions – July 23, 2015. Retrieved May 03, 2017, from https://www.newsreview.com/sacramento/segregation-039-will-happen-if/content?oid=17653788

Millhiser, I. (2015, August 13). American Schools Are More Segregated Now Than They Were In 1968, And The Supreme Court Doesn’t Care, from https://thinkprogress.org/american-schools-are-more-segregated-now-than-they-were-in-1968-and-the-supreme-court-doesnt-care-cc7abbf6651c

Padilla, L. (1995). Reflections on Inclusionary Housing and Renewed Look at its Viability. Hofstra Law Review 23(3), 539-626.

Potter, H., Quick, K., & Davies, E. (2016). A New Wave of School Integration: Districts and Charters Pursuing Socioeconomic Diversity. The Century Foundation. Retrieved from tcf.org.

Orfield, G., & EE, J. (2014). Segregating California’s Future: Inequality and Its Alternative 60 Years after Brown v. Board of Education. The Civil Rights Project.

S. (2015, September 1). AN ORDINANCE REPEALING CHAPTER 17.712 OF, AND ADDING CHAPTER 17.712 AND SECTION 17.808.260 TO, THE SACRAMENTO CITY CODE, RELATING TO MIXED INCOME HOUSING . Retrieved from http://www.qcode.us/codes/sacramento/revisions/2015-0029.pdf

Sacramento City Unified School District. (2012, October 16). Retrieved May 03, 2017, from http://www.scusd.edu/e-connections-post/scusd-student-test-scores-are-rise

Silver, N. (2015, May 1). The Most Diverse Cities Are Often The Most Segregated, from https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/the-most-diverse-cities-are-often-the-most-segregated/

Stuart Wells, A., Fox, L., & Codova-Cobo, D. (2016, February 09). How Racially Diverse Schools and Classrooms Can Benefit All Students. Retrieved May 03, 2017, from https://tcf.org/content/report/how-racially-diverse-schools-and-classrooms-can-benefit-all-students/

U. (2015, August 6). Fair Housing Act. Retrieved May 03, 2017, from https://www.justice.gov/crt/fair-housing-act-2

U. (n.d.). United States Census: Quick Facts. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts

T. (2010). 1920s–1948: Racially Restrictive Covenants. Retrieved May 03, 2017, from http://www.bostonfairhousing.org/timeline/1920s1948-Restrictive-Covenants.html

Walsemann, K. M., & Bell, B. A. (2010). Integrated Schools, Segregated Curriculum: Effects of Within-School Segregation on Adolescent Health Behaviors and Educational Aspirations. American Journal of Public Health, 100(9), 1687–1695. http://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.179424